Why Remission in Crohn's Is Complicated: Lessons From A Viral Reddit Thread | Gut Check Daily

Crohns Remission Checklist

Download this comprehensive checklist to bring to your next GI appointment. Get evidence-based answers and a clear action plan.

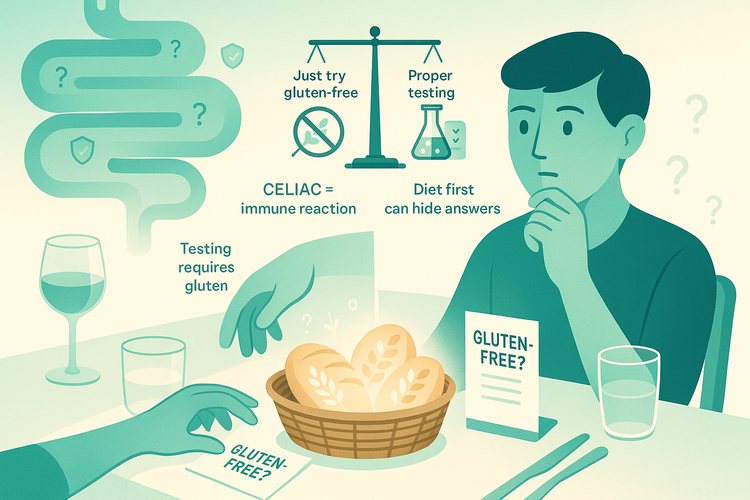

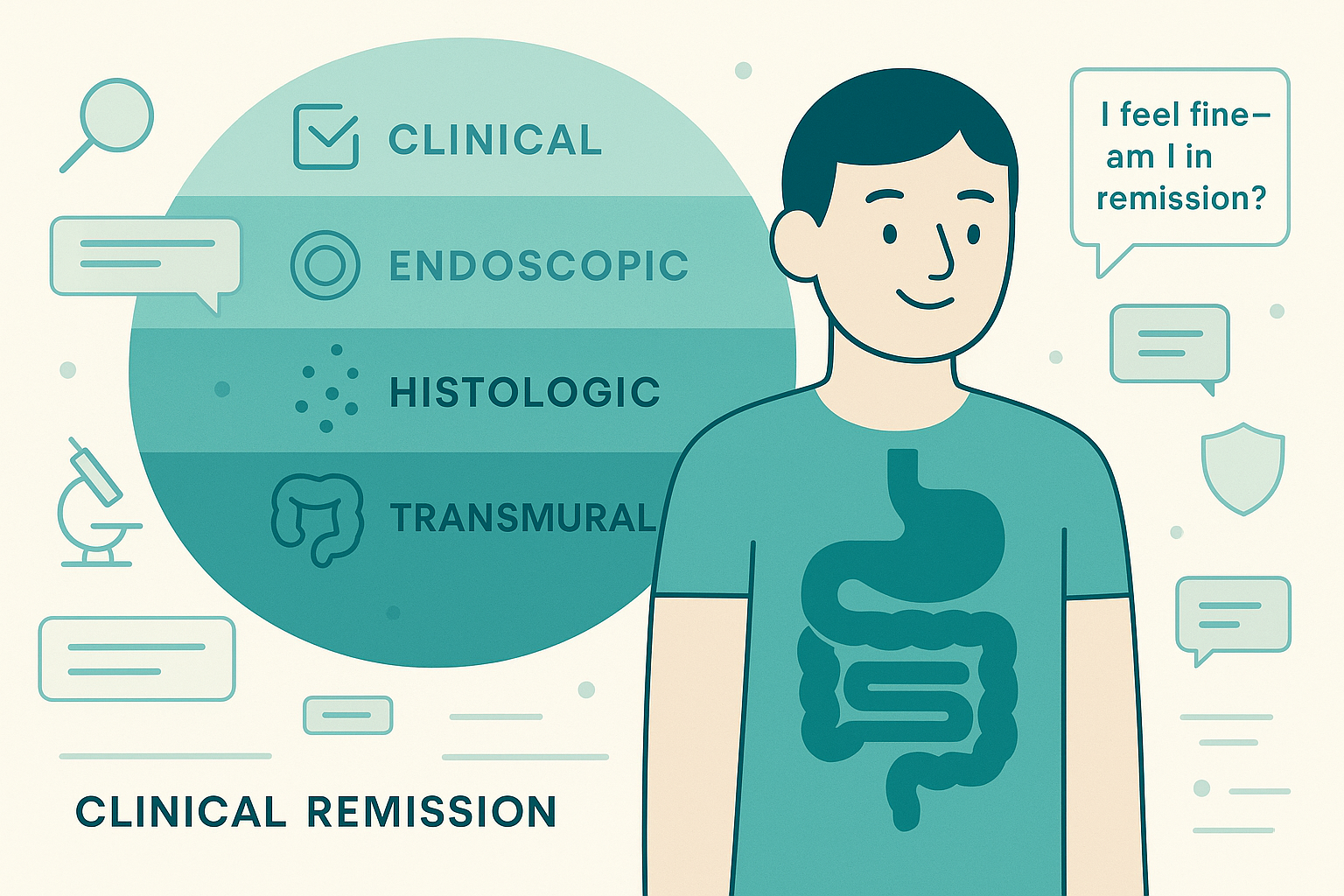

📥 Download PDF Checklist →Clinical vs. endoscopic vs. histologic vs. transmural healing—and why feeling fine doesn't always mean you're in the clear.

1. The four dimensions of remission in Crohn's disease

When your GI talks about "remission," they could mean any of these four things:

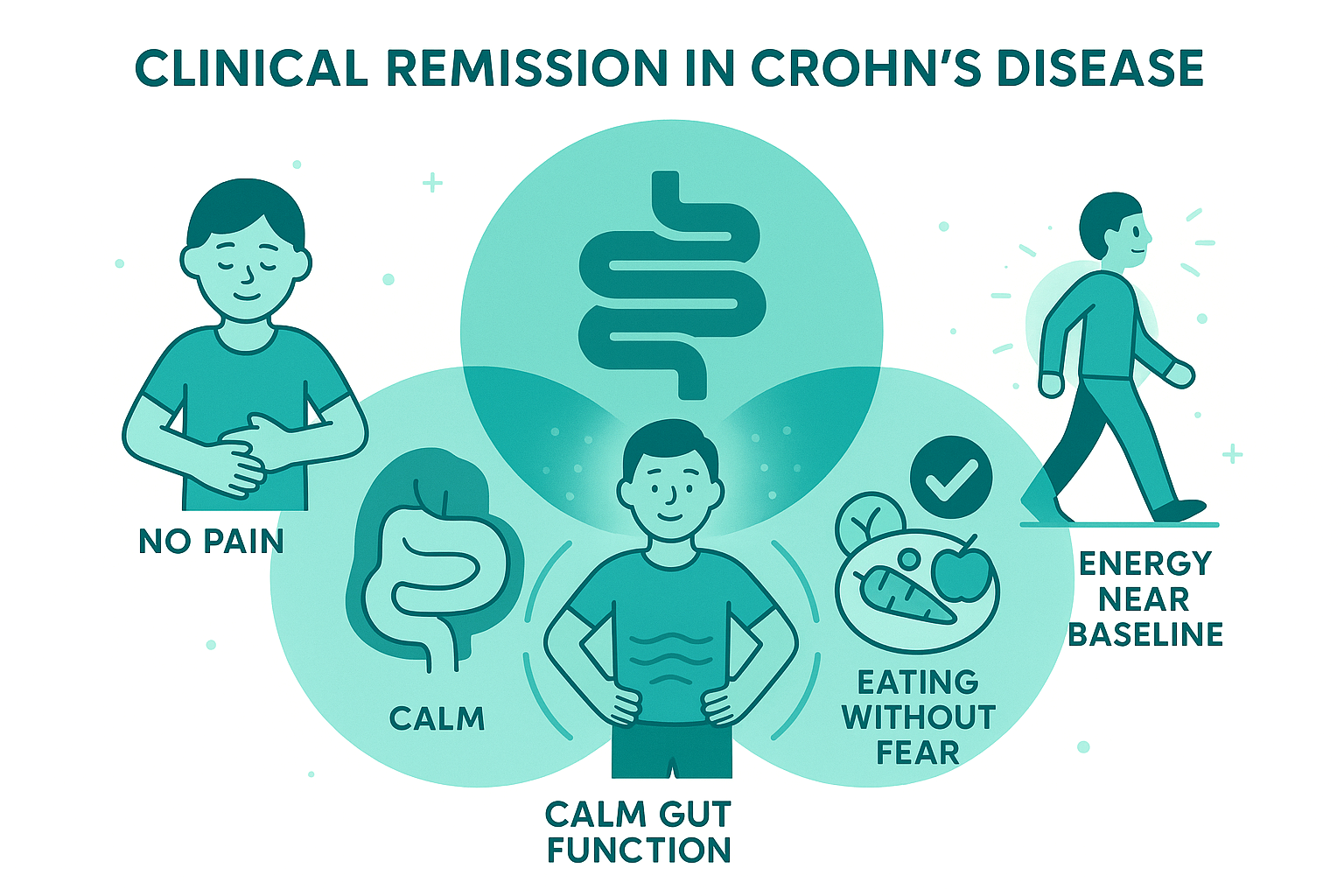

1) Clinical remission

This is the one you experience.

Roughly means: Normal or near-normal bowel movements, No abdominal pain, Eating without fear of obstruction, Energy levels approaching baseline, and Living life without Crohn's dominating your day

This is what patients (understandably) care about most and what older treatment approaches focused on exclusively.

2) Endoscopic remission

This is what the camera sees during colonoscopy or upper endoscopy.

Typical definition: No visible ulcers, No obvious inflammation or cobblestoning, Healed areas that previously showed disease, On scoring systems like SES-CD (Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn's Disease), this usually means very low or zero scores

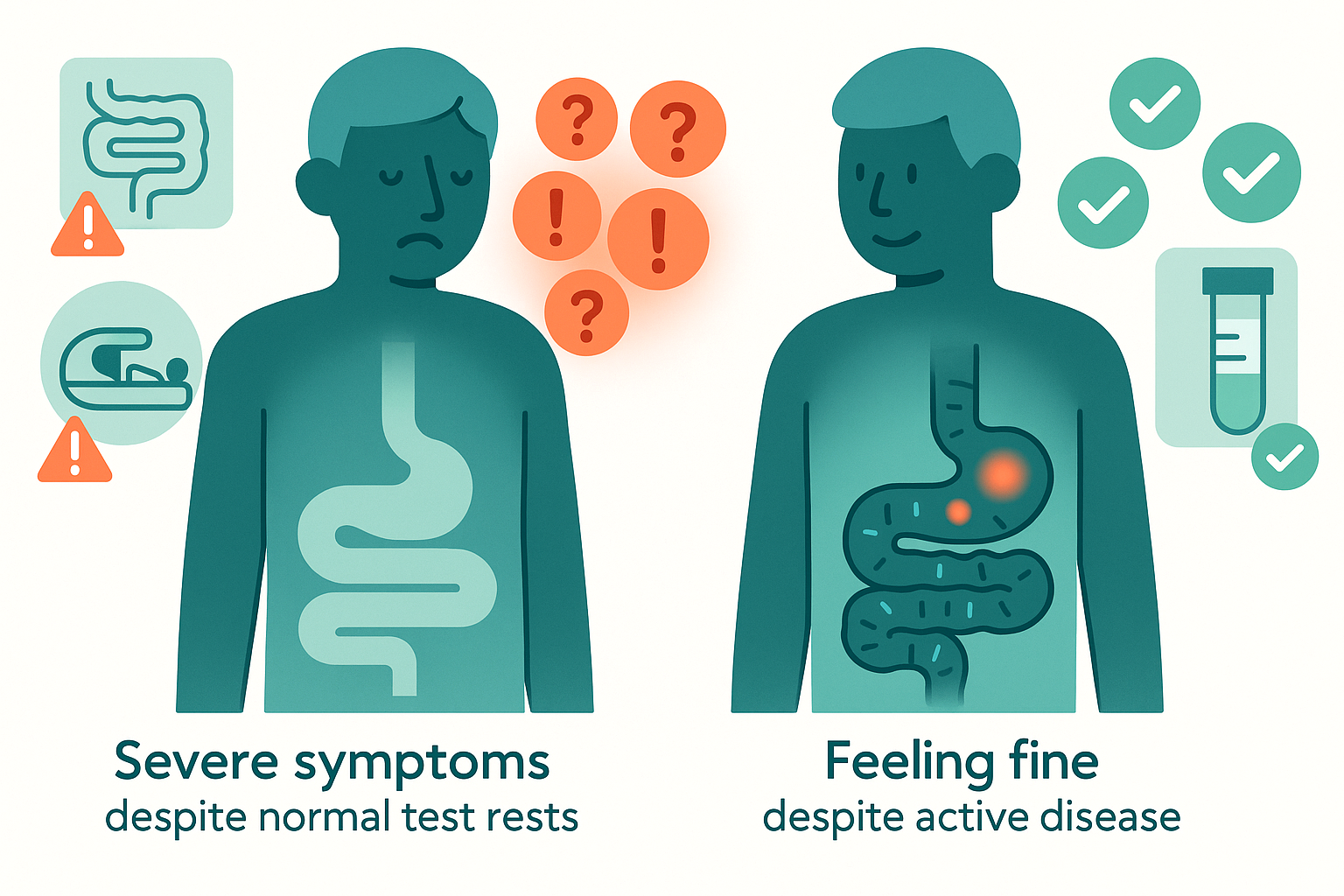

You can feel terrible with a "pretty good" scope. You can also feel fine with moderate inflammation brewing in areas you can't feel.

3) Histologic remission

This is what the pathologist sees under the microscope.

Biopsies are taken even from areas that look normal. The pathologist looks for: Active inflammatory cells (neutrophils, eosinophils), Microscopic ulceration or erosions, Chronic architectural changes, Granulomas (though these can persist even in remission)

Histologic remission means the tissue looks "quiet" at the cellular level, with no signs of active inflammation.

4) Transmural healing

This is unique to Crohn's disease.

Unlike UC, which affects only the inner lining of the colon, Crohn's inflammation goes through the full thickness of the bowel wall (transmural inflammation). This is why Crohn's can cause: Strictures (narrowing from scar tissue through the wall), Fistulas (abnormal tunnels through the wall to other organs), Abscesses (infections in or around the bowel wall)

Transmural healing is assessed through: MRI enterography (MRE), CT enterography (CTE), Intestinal ultrasound (more common in Europe)

These imaging tests can show bowel wall thickness, edema, enhancement patterns, and complications that colonoscopy can't see.

Why all four matter:

Studies increasingly show that patients who achieve deep remission (endoscopic + histologic + transmural healing) have: Longer disease-free intervals, Lower rates of strictures and fistulas, Reduced need for hospitalization, Less need for surgery over time, Better quality of life long-term

This doesn't mean every patient needs to chase all four targets at all costs, but it explains why your GI might push treatment adjustments even when you feel okay.

2. The symptom-inflammation disconnect: worse in Crohn's than UC

From the Reddit comments, the same patterns appear repeatedly: "I felt fine but my MRE showed severe wall thickening.", "Colonoscopy looked clean but I'm in constant pain.", "Calprotectin was normal but imaging showed active disease.", "I have terrible symptoms but they say it's just stricture, not inflammation."

This disconnect manifests in several distinct ways in Crohn's:

A. You feel good, but inflammation is silently progressing

Why this matters:

Small bowel inflammation is often completely asymptomatic until complications develop - Ongoing inflammation means repeated cycles of damage and repair, leading to progressive fibrosis - Strictures can develop silently over years, becoming symptomatic only when severely narrowed - Fistulas can form without obvious external symptoms - By the time symptoms appear, structural damage may require surgery rather than medical management

From a long-term perspective, "I feel fine" plus "active inflammation on imaging" is a ticking time bomb, not a win.

B. You feel awful, but tests show controlled inflammation

Multiple people in the comments described: - Clean colonoscopy and normal calprotectin, but severe pain and diarrhea - MRE showing only mild wall thickening, but debilitating symptoms - "In remission" according to biopsies, but daily suffering - Stricture causing symptoms without any active inflammation

Common explanations:

Stricture without active inflammation: Scar tissue from previous inflammation causes narrowing, This creates pain, bloating, and partial obstructions, Anti-inflammatory drugs won't help because it's fibrotic, not inflammatory, May need stricture dilation or surgery

IBS overlay: Very common in Crohn's patients, Can cause symptoms identical to active disease, Requires different treatment (gut-brain modulators, dietary changes, pelvic PT)

Visceral hypersensitivity: Years of inflammation can make nerves more sensitive, Normal gut contractions feel painful, Requires neuromodulators, not more immunosuppression

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO): Can occur with strictures or after surgeries, Causes bloating, pain, diarrhea, Treated with antibiotics, not biologics

Bile acid diarrhea: Common after ileal resection or with ileal disease, Causes watery diarrhea, Treated with bile acid sequestrants

Medication side effects: Biologics, methotrexate, and other meds have GI side effects, Can mimic disease activity

C. The perianal Crohn's challenge

Several thread participants described perianal disease (fistulas, abscesses, skin tags, fissures).

The disconnect here: Luminal (intestinal) disease can be in complete remission, Perianal disease remains active or recurring, Or vice versa: perianal disease healed but intestinal inflammation persists

Perianal Crohn's often: Responds poorly to treatments that work well for luminal disease, Requires specialized surgical management (setons, fistulotomy), May need combination therapy or investigational treatments, Can profoundly impact quality of life even when intestinal disease is quiet

Bottom line: Symptoms in Crohn's are real and important, but they're an unreliable thermometer for what's happening at the tissue level.

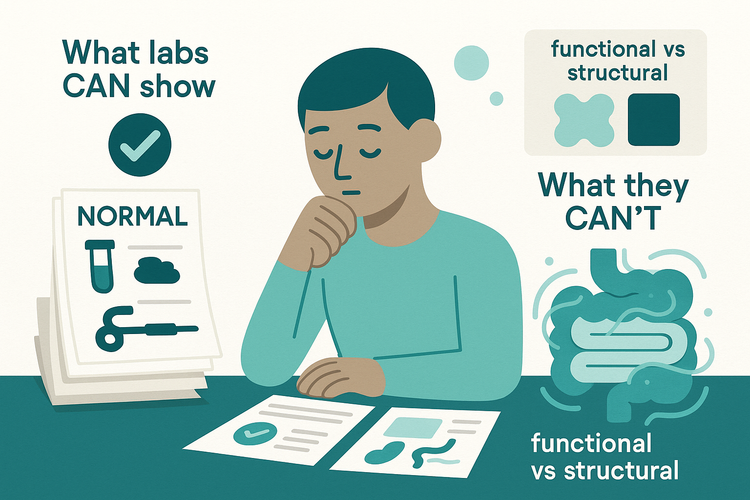

3. How we actually measure inflammation in Crohn's (and what can go wrong)

The most common questions in the thread were about monitoring: "How do I know what's really going on without constant scopes?"

Here are the main tools and their limitations:

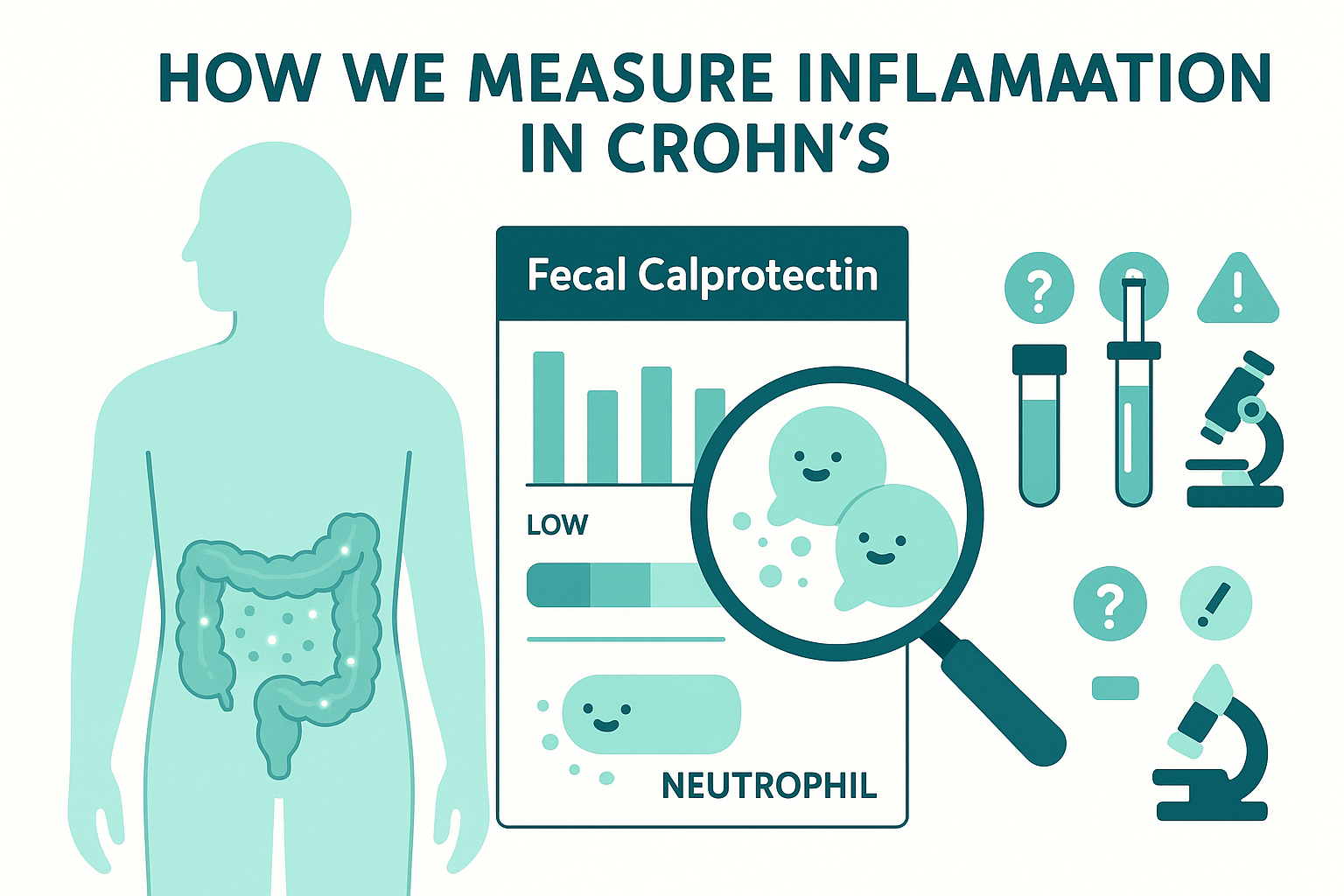

A. Fecal calprotectin

What it is: A protein released by neutrophils that shows up in stool. Higher levels usually indicate intestinal inflammation.

Pros: Non-invasive, Correlates reasonably well with mucosal inflammation in many studies, Useful for tracking trends over time, Helps decide when imaging or scoping is needed, Much less expensive than imaging

Cons:

- Location blindness: Small bowel inflammation may produce lower calprotectin than colonic disease

- Individual variability: Some people's calprotectin never correlates with their disease (several thread participants noted this)

- False elevations: Infections, NSAIDs, PPIs can raise it

- Perianal disease: May not significantly elevate calprotectin

- Strictures without active inflammation: Won't show up on calprotectin

Practical use: Most valuable when you've established your personal pattern through paired calprotectin tests and imaging/scopes. Once that baseline is known, calprotectin can monitor between scopes. A rising trend matters more than any single value. Should always be interpreted alongside symptoms and other data

B. Blood tests

Common markers: CRP (C-reactive protein), ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), Hemoglobin and iron studies, Albumin (low in active inflammation), Platelets and white blood cell count

Pros: Widely available and inexpensive, CRP tends to correlate better in Crohn's than UC - Trends over time can be informative, Anemia markers (hemoglobin, ferritin, iron) identify malabsorption and blood loss

Cons: - Many people with active Crohn's have completely normal CRP. CRP and ESR are non-specific (infections, arthritis, other conditions raise them). Normal blood work doesn't rule out significant intestinal inflammation. Some people never make much CRP regardless of disease activity.

C. Colonoscopy + biopsies

Pros:

- Gold standard for visualizing colonic and terminal ileal disease

- Allows direct assessment of inflammation severity

- Biopsies provide histologic grading

- Necessary for dysplasia surveillance (cancer screening)

Cons:

- Limited reach: Standard colonoscopy only sees the colon and last 10-20cm of terminal ileum

- Small bowel blindness: Can't assess jejunum or most of ileum where Crohn's often hides

- Patchy disease: Biopsies from "normal-looking" areas might miss inflammation elsewhere

- Post-scope flares: Some patients report symptom worsening after prep or procedure

- Cost and access: Especially problematic in the US

- Logistics: Time off work, prep discomfort, sedation

D. Small bowel imaging (MR/CT enterography)

What it shows:

- Bowel wall thickness (>3mm suggests active inflammation)

- Wall enhancement pattern (how much contrast the inflamed wall takes up)

- Strictures and their severity

- Abscesses and fistulas

- Mesenteric inflammation (fat around the intestines) - Complications like obstruction

MRE (MRI enterography):

- No radiation

- Excellent soft tissue detail

- Can differentiate inflammatory vs. fibrotic strictures based on enhancement patterns

- Becoming the preferred test for small bowel assessment

CTE (CT enterography):

- Faster than MRE

- Better for acute scenarios (suspected obstruction, abscess)

- Involves radiation (a concern with repeated scans)

Why it matters for Crohn's:

- Sees what scopes can't: The jejunum, most of the ileum, and full bowel wall thickness

- Transmural assessment: Shows inflammation through the entire wall, not just the surface

- Complication detection: Finds abscesses and fistulas that might be clinically silent

Limitations:

- Not perfect: Can still miss patches of disease

- Cost: Often $1000-3000+

- Preparation: Requires drinking oral contrast (can be unpleasant)

- Interpretation variability: Radiologist experience matters

E. Capsule endoscopy (pill cam)

What it is: A pill-sized camera you swallow that takes thousands of images as it travels through your entire GI tract.

When it's used:

- When Crohn's is suspected in the small bowel but MRE/CTE and colonoscopy are inconclusive

- To assess extent of small bowel disease

- When other tests don't explain symptoms

Pros:

- Visualizes the entire small bowel surface

- Non-invasive (just swallow a pill)

- Can find lesions other tests miss

Cons:

- Stricture risk: Can get stuck if there's a tight stricture (requires patency capsule test first)

- No biopsies: Can see disease but can't sample it

- Can't treat: If it finds something, you still need conventional endoscopy or surgery

- Expensive: $1000-2000+

- Reading time: Someone has to review thousands of images

F. Intestinal ultrasound

What it is: Specialized ultrasound that can measure bowel wall thickness, blood flow, and inflammation.

Pros:

- Non-invasive

- No radiation

- No IV contrast

- Can be done in clinic

- Relatively inexpensive

- Can be repeated frequently

Cons:

- Requires specialized training ("certified GI ultrasound")

- More common in Europe than North America

- Operator-dependent (quality varies by who's doing it)

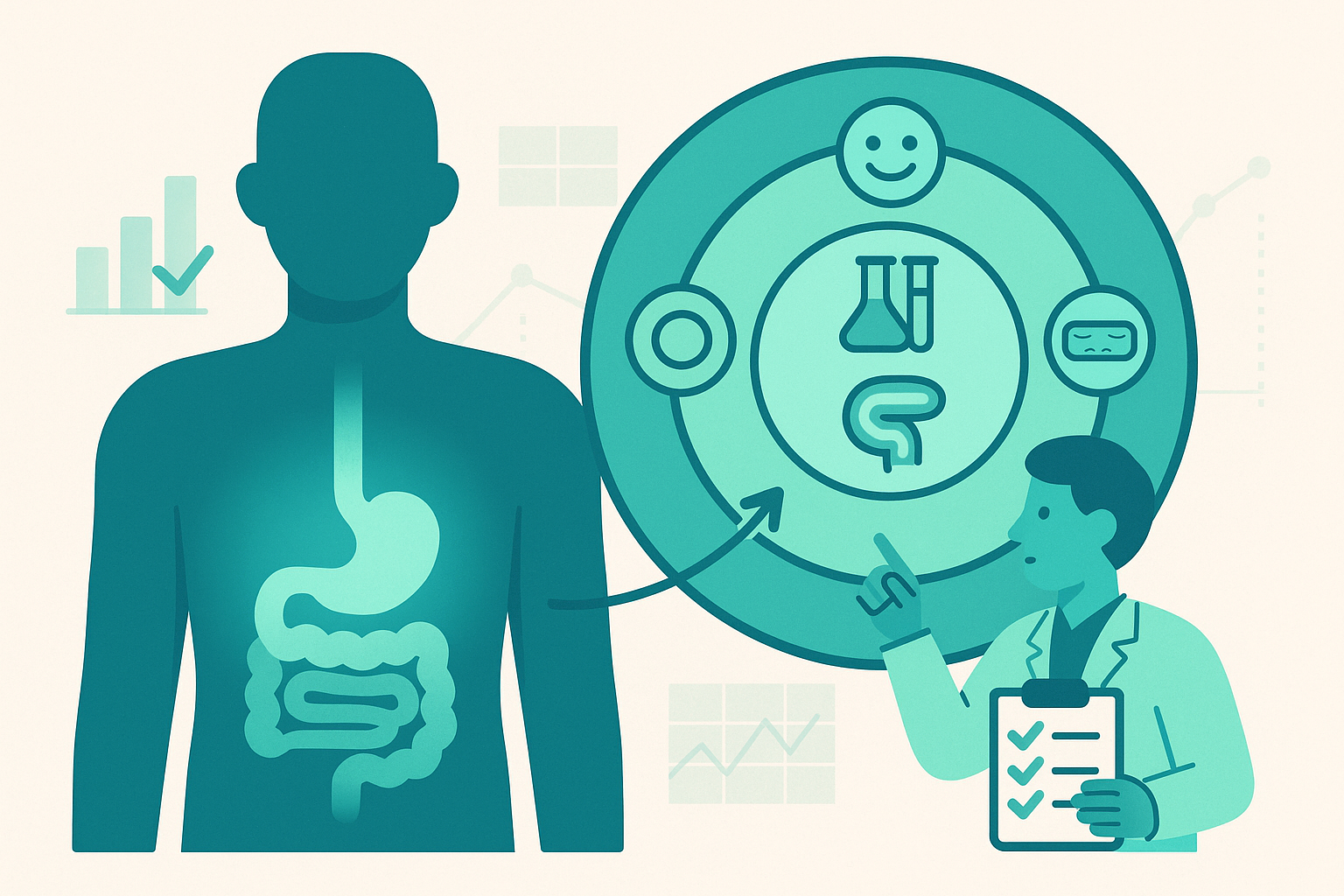

4. What "treat to target" means in Crohn's disease

The field has moved toward "treat-to-target" approaches, formalized in STRIDE and STRIDE-II guidelines.

Core principle:

- Instead of "treat until symptoms improve, then wait and see," we:

- Define clear, objective targets (symptom resolution, biomarker normalization, endoscopic healing, transmural healing)

- Monitor those targets with testing

- Adjust treatment when we're off target, even if symptoms are controlled

STRIDE-II targets for Crohn's:

Short-term (first few months): Clinical remission (symptom control), Improved quality of life, Resolution of extra-intestinal manifestations (arthritis, skin issues, etc.)

Medium-term (6-12 months): Normalization or near-normalization of CRP and calprotectin, Reduction in corticosteroid use (should be off steroids by 3-6 months)

Long-term (12-24 months and beyond): Endoscopic healing (absence of ulceration), Transmural healing on MRE/CTE when feasible, Prevention of complications (strictures, fistulas, abscesses), Prevention of disability and surgery

Aspirational: Histologic remission (increasingly recognized but not yet a formal target in all guidelines)

What this looks like in practice:

- When you start a biologic or switch therapies, the goal isn't just "feel better"

- We want objective proof that inflammation is controlled: normal or near-normal calprotectin, healing on colonoscopy, reduced wall thickness on MRE

- If you feel fine but imaging shows persistent disease, treatment may be optimized - If biomarkers trend upward even without symptoms, that triggers investigation

Important nuances:

- "Ideal textbook target" and "realistic target for this specific patient" aren't always identical

-Factors influencing the specific target: Disease location and severity, Prior complications (surgeries, hospitalizations, strictures), Age and life stage, Treatment history (how many biologics have failed?), Side effect profile and quality of life on current regimen, Patient priorities and risk tolerance, Access and cost

- Not every study shows benefit from pushing all the way to complete histologic remission in every patient

- Perianal disease often requires different targets and timelines than luminal disease

- Some patients with mild disease do well with less aggressive targets

Shared decision-making is critical:

Treat-to-target should not be a rigid algorithm imposed on patients. As one thread participant (a social worker with Crohn's) noted: "Person-centered care and advocacy" matter enormously.

Your input on:

Treatment burden, Side effects you're willing to tolerate, Quality of life priorities, Risk tolerance

...should shape which targets are pursued and how aggressively.

5. The biologic "treatment runway" problem: when you keep failing medications

This theme came up powerfully in the thread, especially from people who've had Crohn's for decades.

Why loss of response happens:

Immunogenicity (antibody formation): - Your immune system can develop antibodies against the biologic drug

- These antibodies neutralize the drug or cause infusion/injection reactions

- More common with anti-TNF drugs (infliximab, adalimumab)

- Can be detected with drug level and antibody testing

How to prevent/delay it:

- Combination therapy: Adding an immunomodulator (azathioprine, 6-MP, methotrexate) can suppress antibody formation and prolong biologic effectiveness - Thread example: Rheumatologist added methotrexate to monthly Stelara, which resolved previously uncontrolled joint pain

- Optimize dosing: Moving from standard to intensified dosing (e.g., Humira weekly instead of biweekly) can overcome partial loss of response

- Proactive monitoring: Checking drug levels and antibodies before loss of response allows earlier intervention

True disease progression:

- Sometimes the disease mechanism shifts and a different pathway becomes dominant

- A drug targeting one pathway (e.g., TNF) may stop working as other pathways take over

Non-adherence:

- Missing doses, even occasionally, can trigger antibody formation

- Maintaining consistent levels is critical

The strategic dilemma:

Should you start biologics early and aggressively, or save them for when really needed?

Arguments for early aggressive treatment: Prevent structural damage (strictures, fistulas) that becomes irreversible, Deep remission early in disease may alter disease course long-term, "Window of opportunity" in early Crohn's

Arguments for step-up approach: Preserves biologic options for later (the "runway" concern), Avoids exposing young patients to decades of immunosuppression if milder therapy works, Lower upfront cost and side effect burden

Current evidence leans toward early aggressive treatment for moderate-severe Crohn's, but this remains personalized based on: Disease severity and location, Risk factors (young age at onset, perianal disease, extensive small bowel involvement), Patient values and preferences

6. Special challenges: strictures, fistulas, and when surgery becomes the answer

A. Strictures: inflammation vs. fibrosis

Strictures (narrowing of the intestine) came up frequently in the thread.

The critical distinction:

Inflammatory stricture:

- Caused by active swelling and inflammation

- Shows enhancement on MRE (lots of blood flow)

- May respond to anti-inflammatory treatment

- Can potentially reverse with medication

Fibrotic stricture:

- Caused by scar tissue from repeated inflammation

- Shows minimal enhancement on MRE (not much blood flow)

- Will NOT respond to anti-inflammatory drugs

- Cannot reverse with medication

- Requires endoscopic dilation or surgery

Mixed stricture: - Combination of inflammation and fibrosis

- Partial response to medication possible

- May still need mechanical intervention

Management options:

Endoscopic balloon dilation:

- For short strictures (<5cm) that aren't too tight

- Can be repeated if needed

- Avoids surgery

- Done by IBD specialists or advanced endoscopists

Surgery (stricturoplasty or resection):

- For longer strictures, multiple strictures, or failed dilation

- Stricturoplasty widens the bowel without removing it (preserves intestinal length)

- Resection removes the diseased segment

- Outcomes are better when inflammation is controlled first

B. Fistulas: the treatment-resistant complication

Fistulas are abnormal connections between the intestine and other structures:

- Enteroenteric: Between loops of intestine

- Enterocutaneous: To the skin surface

- Perianal: Around the anus

- Enterovesical: To the bladder

- Enterovaginal: To the vagina

Why fistulas are so challenging:

- Require different treatment approach than luminal inflammation

- Often need surgical drainage (setons for perianal fistulas)

- Medical therapy alone rarely achieves fistula closure

- Can persist even when intestinal inflammation is in complete remission

- Profoundly impact quality of life

Investigational approaches: Stem cell therapy for perianal fistulas (in trials), Fistula plugs and tissue sealants, New biologics specifically tested for fistulizing disease

Realistic expectations:

As noted in the thread response about perianal Crohn's: "It's one of the hardest forms to get fully into remission. Often multiple therapies or stronger doses are needed."

Complete fistula healing is challenging. Realistic goals often include: Reducing drainage, Preventing new fistulas, Controlling pain, Avoiding abscesses and sepsis, Maintaining quality of life

C. When surgery is the right answer

Surgery came up in many thread comments, often with anxiety and uncertainty.

Common scenarios where surgery is appropriate:

1. Fibrotic stricture with obstruction: Medical therapy can't reverse scar tissue, Recurrent obstructions despite treatment, Surgery prevents emergency situations

2. Abscess that needs drainage: Antibiotics alone often fail, Percutaneous drainage or surgical intervention needed, Can allow time for biologics to work

3. Fistula complications: Recurrent abscesses despite medical therapy, Complex fistulas not responding to biologics + setons

4. Refractory disease: Failed multiple biologics, Persistent symptoms despite maximal medical therapy, Quality of life severely impacted

5. Dysplasia or cancer: Strictures preventing adequate colonoscopy surveillance, Confirmed dysplasia or cancer

6. Growth failure in children: When medical therapy fails to restore normal growth

Important surgical principles:

Surgery is not failure: Sometimes surgery provides better quality of life than continuing medical therapy, Can be complementary to medication, not replacement, For some patients, removing a short diseased segment and continuing biologics prevents recurrence better than medication alone

Bowel-sparing approaches when possible: Stricturoplasty instead of resection, Limited resections, Every surgery removes more intestine; preserving length matters long-term

Post-surgical monitoring matters: High risk of recurrence at anastomosis (surgical connection), Endoscopy 6-12 months after surgery to check for early recurrence, Biologics started or continued post-op to prevent recurrence, Rutgeerts score: grading system for post-surgical recurrence

7. Monitoring strategies: how often should you test?

This was one of the most common questions: "How often do I need scopes, imaging, blood work, calprotectin?"

There's no universal answer, but here are frameworks:

A. Colonoscopy frequency

Two separate purposes:

1. Disease activity monitoring / treatment response

When scopes are done:

- After diagnosis to establish baseline severity

- 6-12 months after starting new biologic to confirm mucosal healing

- When symptoms, biomarkers, and clinical picture don't align

- When considering major treatment changes

- To investigate suspected complications

2. Dysplasia (cancer) surveillance

General guidelines:

- Start surveillance around 8-10 years after Crohn's colitis onset

- Frequency: every 1-5 years depending on:

- Extent of colonic involvement

- Degree of inflammation over time

- Presence of PSC (primary sclerosing cholangitis)

- Family history of colon cancer

- Prior dysplasia or polyps

- Strictures that limit exam

General approach:

- Newly diagnosed or changing treatment: More frequent (every 6-18 months)

- Stable deep remission with good biomarker correlation: Less frequent (every 2-3 years for activity, plus surveillance timeline)

- High-risk features: More frequent regardless of symptoms

B. MR or CT enterography frequency

Small bowel imaging intervals:

- Active disease or changing treatment: Every 6-12 months to assess response

- Stable disease: Every 1-2 years if clinically indicated

- Suspected complication: Immediately (don't wait for scheduled interval)

Note: MRE preferred over CTE for repeated imaging to avoid cumulative radiation exposure.

C. Calprotectin monitoring

Frequency depends on disease stage:

Active disease or recent treatment change: Every 2-3 months to track response, More frequent if adjusting dosing

Stable remission with known correlation: Every 6-12 months as routine monitoring, Plus when symptoms change

Poor correlation with your disease: Less useful; don't waste money on tests that don't reflect your biology, Some people's calprotectin simply doesn't track their disease

D. Blood work frequency

On immunosuppressive therapy: CBC, CMP, LFTs every 3 months (to monitor for medication side effects)

CRP monitoring: Every 3-6 months if it correlates with your disease, When assessing treatment response, During suspected flare

Nutritional monitoring: Vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron studies annually or more often if history of deficiency, Albumin as marker of nutrition status and inflammation

E. Drug level monitoring

For anti-TNF biologics (infliximab, adalimumab): Check trough levels and antibodies: If loss of response suspected, If symptoms return despite previously working, Periodically (every 6-12 months) to optimize dosing proactively

For other biologics: Therapeutic drug monitoring less established but emerging

F. Putting it together: a sample monitoring plan

Year 1 after diagnosis on new biologic: Calprotectin: every 3 months, Blood work: every 3 months, Colonoscopy + MRE: 6-12 months to assess mucosal and transmural healing

Stable remission years 2-5: Calprotectin: every 6 months, Blood work: every 3-6 months, Colonoscopy: every 2-3 years (or per dysplasia surveillance schedule), MRE: as needed if biomarkers rise or symptoms change

Long-standing remission (5+ years): Calprotectin: annually, Blood work: every 6 months, Colonoscopy: per surveillance schedule, MRE: only if clinically indicated

This is a framework, not a prescription. Your plan should be individualized based on:

- Disease location and behavior (stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory)

- Treatment history

- Biomarker reliability in your case

- Prior complications

- Access and cost

8. When data and symptoms don't match: navigating the disconnect

Scenario A: "I feel fine, but my tests show active disease"

This was extremely common in the thread and often emotionally loaded.

Why doctors push treatment escalation: - Persistent inflammation drives structural damage over decades - Small bowel disease can be completely asymptomatic until complications - Preventing strictures and fistulas is easier than treating them - By the time symptoms appear from structural damage, medication may not help

What a reasonable conversation includes:

Review the data together: Look at actual images and reports, not just "there was inflammation", Understand what "moderate" or "severe" means specifically, Compare to prior studies. Is it better, worse, or stable?

Discuss options explicitly: Optimize current medication (dose increase, frequency change, add combination therapy), Switch drug class (different mechanism), Wait and monitor more closely (accept some risk), Do nothing and repeat imaging in 6 months

Acknowledge the emotional challenge: "I feel good" makes treatment escalation counterintuitive, Fear of new side effects or losing what's working, Financial burden, Treatment fatigue

Negotiate a middle path: Example: Modest dose increase + closer biomarker monitoring + planned repeat imaging in 6 months, Time-limited trial of adjustment with clear endpoints

Response emphasized: Long-term inflammation increases complication risk even without symptoms. But treatment decisions should be shared, not imposed.

Scenario B: "My tests say remission, but I feel terrible"

Also very common and deeply frustrating.

What to explore:

Double-check the inflammation assessment: Request actual pathology report, not summary - Any areas of mild inflammation that were minimized? - Did biopsies sample enough sites? - Could there be inflammation in small bowel not assessed? - Infections ruled out? (C. diff, CMV, parasites)

Look for structural issues: Stricture causing partial obstruction? Fistula not detected? Adhesions from prior surgery?

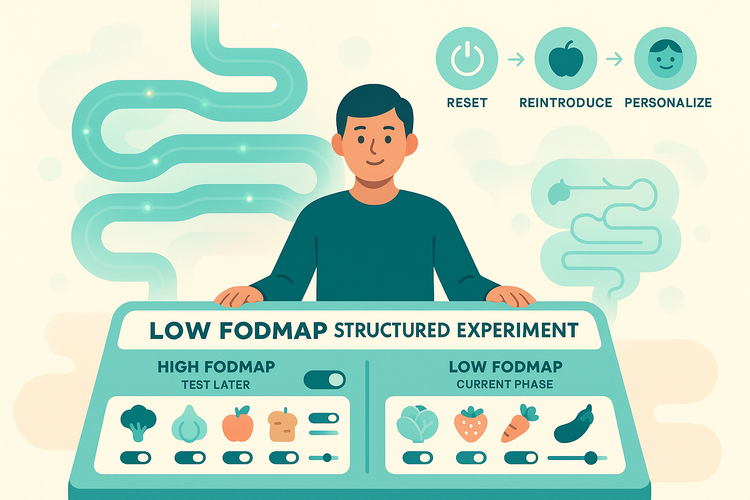

Consider non-IBD GI issues: IBS (very common overlap), SIBO (especially with strictures or resections), Bile acid diarrhea (after ileal disease or resection), Celiac disease, Pancreatic insufficiency, Gastroparesis

Look beyond the gut: Pelvic floor dysfunction, Medication side effects (biologics can cause fatigue, headaches, joint pain), Extraintestinal manifestations (arthritis, skin issues), Nutritional deficiencies (B12, iron, vitamin D), Thyroid disease, Depression/anxiety (both common in IBD and can worsen GI symptoms)

What to ask your doctor:

"If my inflammation is truly under control, what's your working diagnosis for my ongoing symptoms?"

"What's our plan to address these symptoms specifically, not just the IBD?"

"Can we get copies of the full reports to review together?"

Your symptoms are valid even when tests look good. They may just need a different treatment approach than immunosuppression.

9. Practical questions from the thread, answered directly

"Do breakthrough flares on a biologic mean it's failing?"

Not necessarily.

Key questions: Was there an obvious trigger? (Infection, antibiotics, new medication, stress, missed doses) How long did symptoms last? What happened to biomarkers? Were drug levels and antibodies checked?

Possible scenarios:

Temporary trigger with intact drug response: Brief flare from infection or missed dose, Settles with short steroid course, Biomarkers return to baseline, Endoscopy still shows healing → Biologic still working

True loss of response: Gradual symptom return over weeks/months, Rising calprotectin despite adherence, Antibodies detected or low drug levels, Imaging shows increasing inflammation → Need optimization or switch

"Should I push for an earlier scope if I'm feeling good?"

Depends on context.

Good reasons to discuss earlier scoping: Never had post-treatment confirmation of healing after starting biologic, Biomarkers trending up despite stable symptoms, Last scope showed significant inflammation; confirming healing would inform future monitoring, High-risk disease (young onset, extensive involvement, prior complications)

Reasonable to wait: Recent high-quality scope already confirmed deep remission, Stable symptoms and biomarkers, No realistic next treatment step if scope showed mild residual inflammation, Already on maximally optimized regimen

"My GI wants to stop my meds since I'm in remission. Should I?"

This didn't come up directly in the thread but is a common question.

Evidence strongly suggests: Stopping medications during remission leads to high relapse rates (50-80% within 1-2 years), Relapse after stopping can be more severe than original presentation, May develop antibodies during the "off" period, making the drug not work if restarted

Very limited scenarios where stopping might be considered: Medication-induced serious complication requiring discontinuation, Pregnancy planning (though many IBD drugs are safe in pregnancy), Patient preference after extensive discussion of risks

Most guidelines: Continue maintenance therapy indefinitely.

"Can scopes trigger flares?"

Many people in the thread reported this.

Possible mechanisms: Bowel prep disrupts microbiome, Mechanical trauma from scope, Gas insufflation causes distension, Underlying disease was undertreated and prep/scope stress revealed it

What to do: Discuss prep type (some are gentler than others), Question whether frequency is truly necessary, Ask if non-invasive monitoring can replace some scopes, Ensure disease is adequately treated (not just "looking clean")

But don't avoid necessary surveillance because of this concern.

"What about the costs? I can't afford $1200 scopes annually."

Extremely valid concern raised in the thread.

Options to explore:

- Calprotectin as surrogate marker between scopes

- Patient assistance programs for testing

- Negotiate scope frequency based on biomarker correlation

- Transparent discussion with GI: "I can't afford annual scopes. How can we monitor effectively within my budget?"

- Consider non-invasive monitoring more heavily if cost is prohibitive

Note: In many countries (Canada, UK, most of Europe, Australia), scopes are covered publicly. This is primarily a US problem.

"How do I know if a stricture is inflammatory vs. fibrotic?"

MRE/CTE can help distinguish:

- Inflammatory: Marked enhancement (bright on contrast imaging), wall edema, adjacent fat stranding

- Fibrotic: Minimal enhancement, no edema, narrowed lumen

But often it's mixed, and sometimes you only know after trying medical therapy:

- If anti-inflammatory treatment improves symptoms → likely had inflammatory component

- If no improvement despite optimized treatment → likely fibrotic

This is where treat-to-target helps: Control inflammation early to prevent fibrosis from developing.

"Should young patients delay biologics to save them for later?"

Thread participant raised this: Their GI now delays biologics in young patients due to seeing people "run out" of options after decades.

This is an active debate:

Arguments for early biologic use: Prevent irreversible damage in "window of opportunity", Altering disease course early may reduce lifetime treatment burden - Newer drugs keep expanding options

Arguments for delayed use: Preserves treatment runway, Avoids decades of immunosuppression if milder therapy works, Biologics have risks (infections, rare cancers, infusion reactions)

Current consensus leans toward: Risk-stratify at diagnosis, High-risk patients (extensive disease, deep ulcers, young age, perianal disease): start biologics early, Lower-risk patients (limited disease, mild findings): reasonable to try conventional therapy first, But don't delay biologics if conventional therapy isn't achieving targets

"What are the new drugs in development for fistulas specifically?"

Some areas of active research: Mesenchymal stem cell therapy (some already approved in Europe for perianal fistulas), Fistula plugs with growth factors, New anti-inflammatory pathways that may work better for fistulizing disease, Local injection therapies

But realistically: Fistulas remain one of the hardest complications to treat.

10. A practical checklist for your next GI appointment

You don't need to memorize guidelines or scoring systems. You need a framework for productive conversations.

Questions to bring:

1. "What type of remission am I in right now?" Clinical? Endoscopic? Histologic? Transmural? Which are confirmed vs. assumed? When was each last assessed?

2. "What are my monitoring tools, and how well do they work for me?" - Does my calprotectin track with scopes/imaging? Does my CRP correlate with disease activity? How often should we repeat each test?

3. "What's our long-term target for my specific case?" Are we aiming for endoscopic healing? Transmural healing? Histologic remission? Why or why not for me specifically? What are we trading off?

4. "What's our plan if I have a flare?" What symptoms should prompt me to call immediately vs. wait for appointment? Do we have a "bridge" plan (steroids, rescue therapy)? At what point would we consider changing the biologic?

5. "Can we review my actual reports together?" Colonoscopy report with photos, MRE/CTE report with images, Pathology report (not just "mild inflammation" but actual description), Calprotectin trends over time

6. "If my symptoms and tests don't match, what's our approach?" Agree in advance how to handle discordance, What additional testing would we do? What non-IBD issues should we investigate?

7. "How does today's decision affect my 10-20 year outlook?" Not just symptom relief this month, Prevention of strictures, fistulas, surgery, Quality of life over decades

8. "What are my treatment options if current therapy stops working?" - How many biologics are left? Are we optimizing current drug before switching? What about combination therapy?

9. "What's my cancer surveillance plan?" When should dysplasia surveillance start/continue? How often? Any high-risk features that change the timeline?

10. "Can we discuss costs and make a plan I can actually afford?" - Testing frequency that balances medical need and financial reality, Patient assistance programs, Generic options, Biosimilar options

11. The real goal: playing the long game with Crohn's

Crohn's disease is measured in decades, not months.

You can't feel your calprotectin. You can't see your jejunum. You can't predict when a stricture will form.

But you can:

Understand that feeling good ≠ tissue healing - And use that knowledge to have more informed conversations - Push for objective confirmation of remission, not assumptions - Advocate for appropriate monitoring without over- or under-testing

Recognize that symptom control is necessary but not sufficient Quality of life today matters enormously, But preventing complications over 20-30 years also matters, Both can be true simultaneously

Use shared decision-making, not passive acceptance Your lived experience is essential data, Medical tests provide different essential data, Decisions should integrate both, not dismiss either

Ask for clarity when things don't make sense "Why do you want to change my meds if I feel fine?", "If my tests are normal, why do I feel terrible?", "What are we actually trying to prevent with this plan?"

Are legitimate questions that deserve real answers.

Preserve your treatment runway thoughtfully Optimize each drug before abandoning it, Consider combination therapy to prolong response, Don't let preventable antibody formation waste a drug, But also don't delay necessary escalation out of fear

Prepare for surgery as a tool, not a failure Sometimes surgery provides better quality of life than continuing to cycle through failing medications, Modern surgical techniques and post-op management are better than ever, Surgery + biologic maintenance can prevent recurrence

Stay informed about emerging therapies - More drugs in development than ever before, New mechanisms of action being tested, Fistula-specific treatments coming, The treatment landscape in 2025 is vastly different than 2015

Your job is not to become a gastroenterologist, surgeon, radiologist, or pathologist.

Your job is to:

- Bring your lived experience

- Ask your questions

- Understand your options

- Make informed decisions that align with your values

The medical team's job is to:

- Bring the tools, data, and expertise

- Explain options clearly

- Respect your input

- Partner with you for the long haul

When those two pieces work together, remission stops being a vague label and starts being a concrete, measurable plan that makes sense for your specific life and disease.

And that's what treat-to-target should actually mean.