What causes GERD and how is it treated

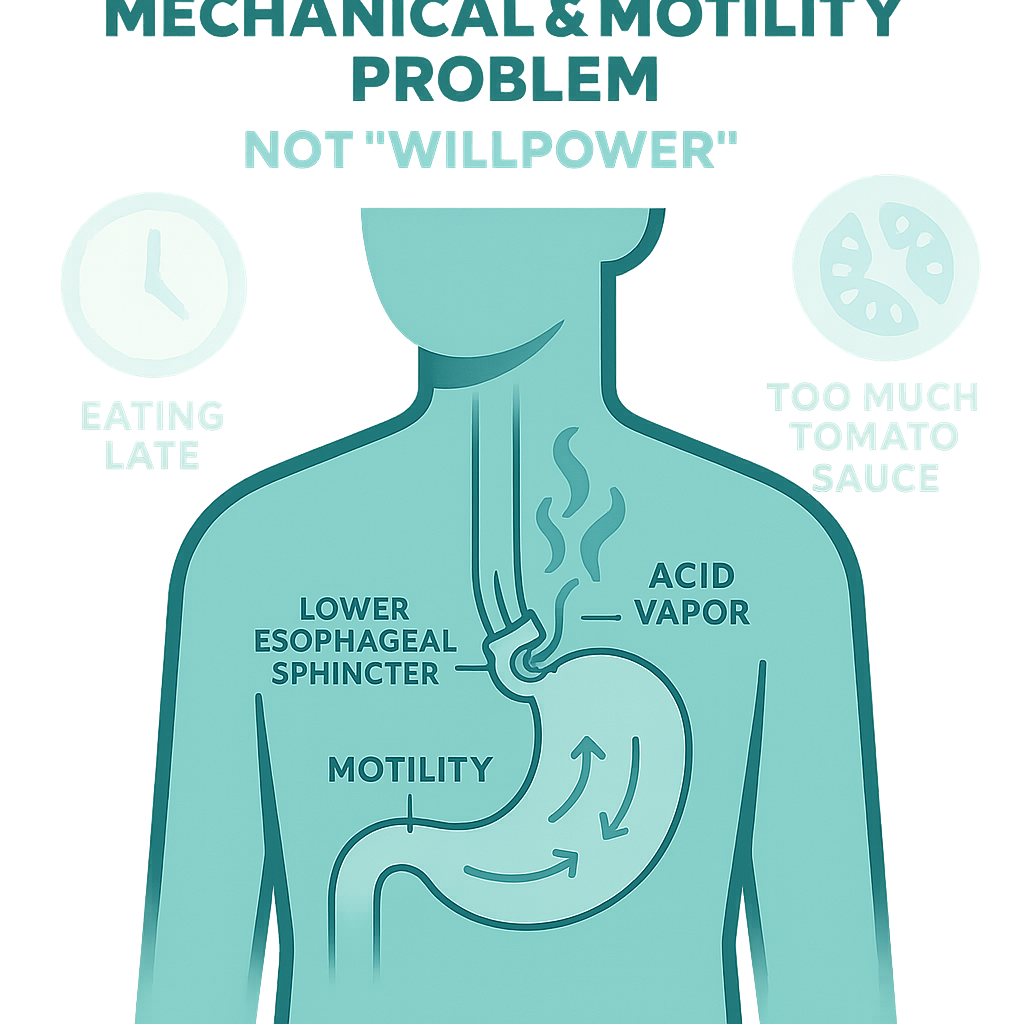

If one more person tells you your reflux is just from eating too late or “too much tomato sauce,” I’m going to throw a proton pump inhibitor at the wall. GERD is not a moral failing or a willpower problem. It’s not just “acid.” It’s a mechanical and motility problem in a very specific piece of anatomy that’s supposed to act like a one-way valve—and in GERD, that system misbehaves. Let’s talk about what’s actually going wrong, and what treatment really targets.

The Mechanism: What’s Actually Malfunctioning

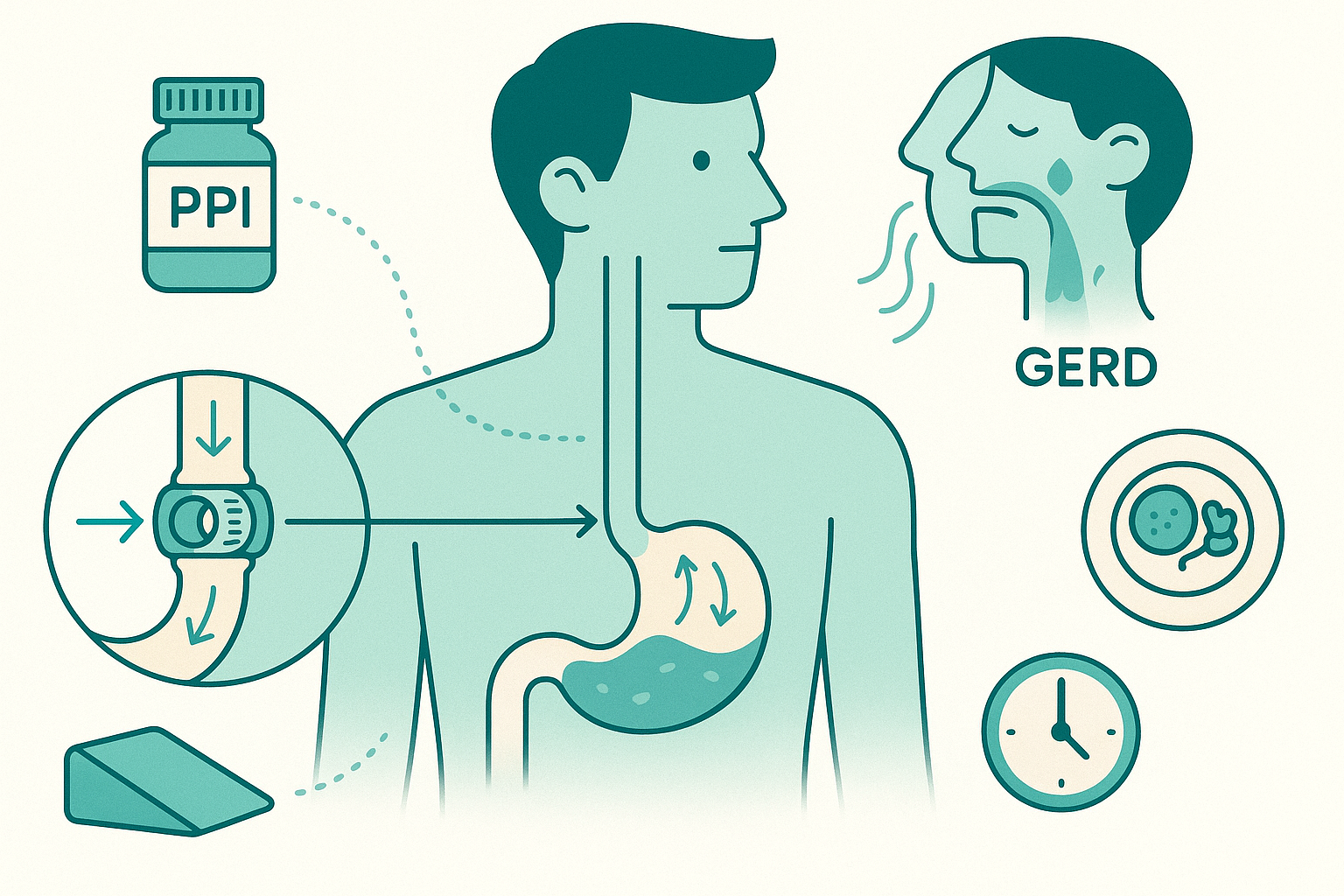

Think of your esophagus as a conveyor belt and your stomach as a sealed bag. Between them is a pressure gate called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Its full-time job: stay tightly closed so stomach contents don’t splash back up, and only open when you swallow.

In GERD, that gate fails in two main ways.

First: transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs). These are brief, inappropriate relaxations of the LES that happen not because you’re swallowing, but out of rhythm with anything useful. The stomach is full, pressure builds, and instead of the gate holding firm, it relaxes for a few seconds. Acid, pepsin, bile, gas—whatever is in there—can wash up into your esophagus. That’s the burning you feel, but the trigger is the relaxation, not simply “too much acid.”

Second: baseline LES weakness. In some people, the LES is just chronically low-pressure. The “valve” doesn’t clamp shut firmly even between TLESRs. It’s like a door that never quite latches. Add normal stomach pressure and you get a quiet, steady leak of reflux, especially when you’re lying down or bending over.

Now add hiatal hernia to the mix. Normally, the LES sits just below the diaphragm, and the diaphragm muscle reinforces it—like a second set of hands on the door. In a hiatal hernia, part of the stomach (and often the LES) slides up into the chest through the diaphragm opening. You lose that reinforcement and that “high-pressure zone.” The valve is literally in the wrong place, and it works worse.

Layer on motility problems. If your esophagus doesn’t contract strongly or in a coordinated way, it can’t clear the refluxed material back down efficiently. Even small reflux events linger longer, so the esophagus gets more acid exposure and more irritation.

So GERD is not “you ate spicy food and angered your stomach.” It’s a combination of: too many inappropriate LES relaxations, a weak or misplaced LES, poor esophageal clearance.

Acid is the chemical that burns, but the plumbing is the main problem.

Clinical Reality: What This Looks Like in Real Life

This is how it usually plays out: you eat, you feel fine for a bit, and then 30–90 minutes later there’s a slow creep of burning behind your breastbone. You might feel food or sour liquid coming up when you bend, tie your shoes, or lie down. Nights can be brutal - two pillows, water on the nightstand, sometimes coughing or choking awake with acid in your throat.

If you have a hiatal hernia, you might notice that anything involving bending or straining, gardening, lifting a laundry basket, even certain yoga poses, makes reflux worse. That’s pressure pushing a poorly positioned valve.

If your motility is sluggish, you might feel food “sticking” or moving slowly, along with regurgitation or a sense that things don’t go down cleanly. Even when acid is suppressed with medication, that stuck or heavy feeling can persist, because the conveyor belt (esophagus) isn’t doing its job efficiently.

People around you (and too often, non-specialist clinicians) cling to the “it’s just lifestyle” narrative. They tell you to avoid spicy food, coffee, chocolate, citrus, tomatoes, and to stop eating after 6 pm. You do all of that, and you’re still up at 2 am chewing antacids and wondering what you’re doing wrong.

Here’s the deal: those foods can increase TLESRs or lower LES pressure slightly in some people, especially in a full stomach. But if your baseline LES is weak or displaced by a hiatal hernia, or your esophagus clears poorly, tweaking your diet alone often feels like rearranging furniture on a sinking ship. You may get partial improvement, but not the full control you were promised.

That disconnect—between simplistic advice and complex physiology, is why you’re frustrated. You’re not imagining it. For a lot of people, GERD is a structural and motility problem that can’t be fully solved by “eat bland and elevate the head of your bed,” even though those tools matter.

Practical Framework: How We Actually Approach GERD

Instead of chasing internet lists of “good” and “bad” foods, it’s more useful to think in terms of pressure, position, plumbing, and chemistry. Then match treatment to which of these is likely driving your symptoms.

First, chemistry: acid suppression. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole reduce acid production, which decreases how corrosive the reflux is. They don’t fix the LES. TLESRs still happen, hiatal hernias still exist, reflux events still occur—but what comes up burns less, so symptoms improve and the esophagus can heal.

That’s why some people on PPIs feel much better but still notice occasional regurgitation, liquid in the throat, or cough. Mechanically, stuff is still moving in the wrong direction; it just hurts less.

Second, pressure and position. Big meals distend the stomach and drive more TLESRs. Lying flat removes gravity from the equation. If your LES is borderline and you have lots of TLESRs, eating smaller meals and not lying flat for 2–3 hours after eating can make a noticeable dent. This isn’t about punishment; it’s about minimizing those “pressure against a weak valve” moments.

If a hiatal hernia is part of your story, position becomes even more important. Reflux with bending, heavy lifting, or after big meals is a clue. Weight around the abdomen also increases intra-abdominal pressure and pushes the stomach upward, which is one reason modest weight loss can significantly improve symptoms, even when your diet quality is already decent.

Third, plumbing: clearance and motility. Some people have weak esophageal contractions. On testing (like high-resolution manometry), we see ineffective peristalsis—weak or disorganized squeezing. In real life, that feels like lingering burn, slow clearance of food, or needing multiple sips of liquid to get things down.

For those patients, acid suppression alone is often not enough. We think about: avoiding very late, large meals to give the esophagus time to clear before sleep, sometimes using alginate-based therapies that form a “raft” on top of stomach contents to reduce backflowin selected cases, addressing coexisting conditions like scleroderma or diabetes-related neuropathy that can worsen motility

Fourth, structural fixes. When the LES is truly dysfunctional or a hiatal hernia is large and driving refractory symptoms, we talk about procedures:

Fundoplication: wrapping the upper part of the stomach around the LES to increase pressure and recreate a barrier. It helps with both baseline LES weakness and reflux from a hiatal hernia (which is usually repaired at the same time).

Magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX): a ring of magnetic beads around the LES to boost closing pressure while still allowing swallowing.

Endoscopic options: various techniques (TIF) to add bulk or stiffness around the LES, with modest and variable results.

These target the valve and its position, not the acid production. That’s why they can be game-changers when medications and reasonable lifestyle changes aren’t enough, especially in younger, otherwise healthy patients.

Through all of this, pattern tracking matters more than rigid rules.

Instead of, “I can never eat tomatoes again,” think: “When I eat a large, high-fat, late dinner and lie down at 11 pm, I wake up with burning and regurgitation.” Versus: “When I eat a smaller portion of the same foods earlier, and stay upright, I’m markedly better.”

That tells you your weak link is more “pressure and position” than one specific ingredient.

Or: “I’m miserable even on high-dose PPIs, my scope shows esophagitis, and I wake up choking with acid in my throat.” That pattern screams mechanical failure, hiatal hernia, severely weak LES, or both, and is the scenario where surgical options should be on the table.

On the flip side: “My heartburn is mild, mostly after overeating or lots of alcohol, and goes away with short courses of meds.” That’s often more about functional TLESRs with otherwise decent anatomy. Long-term heavy medication or surgery is less likely to be necessary.

What we don’t have is a miracle food or supplement that “heals” the LES. Anyone selling a cleanse, a special tea, or some “acid-alkaline protocol” to do that is skipping over basic anatomy. You can support the system, reasonable weight, meal timing, avoiding trigger patterns, but you can’t herbal-remedy a slipped stomach