Understanding IBS testing: Key Takeaways

You’ve done blood work, maybe a stool test, maybe even a scope, and everything comes back “fine.” It can feel like your symptoms are being dismissed. Let’s unpack what those tests are actually doing, what they can’t do, and what “normal” really means when your gut is a mess.

The Mechanism: What Labs Can and Cannot Tell You

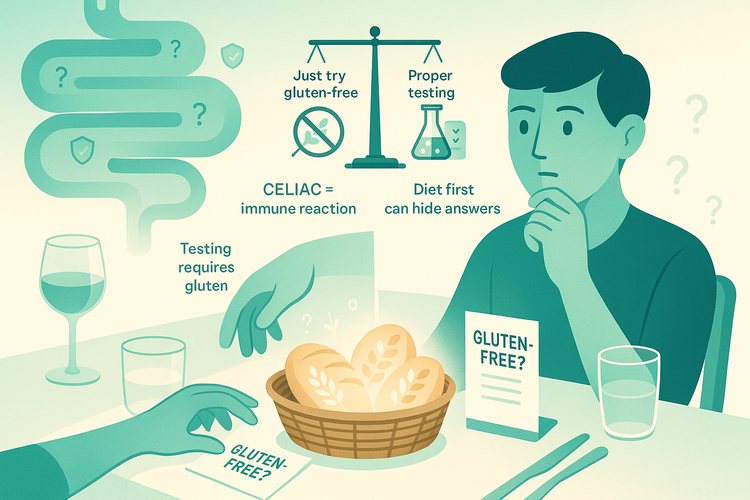

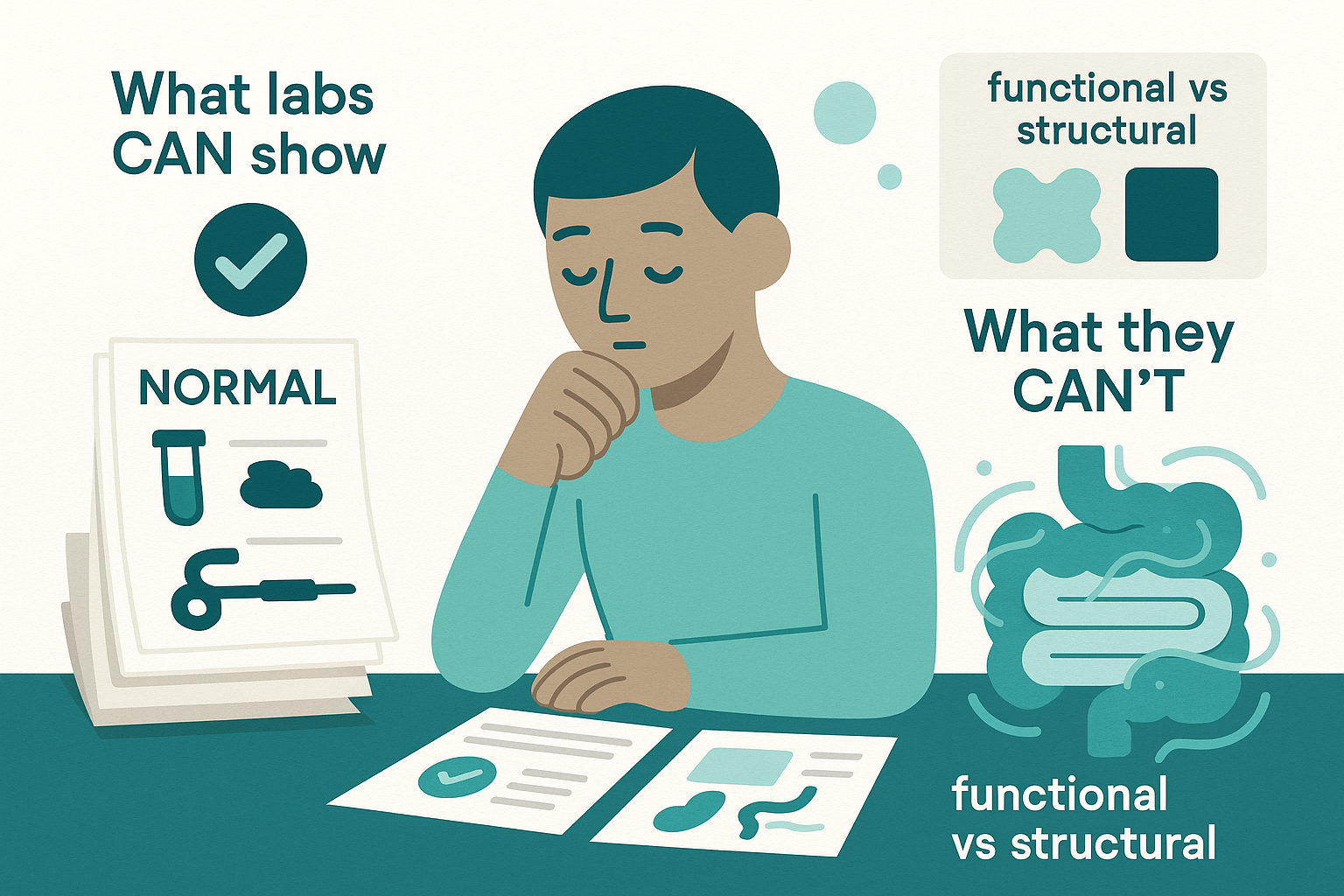

IBS is a functional disorder. That doesn’t mean “it’s in your head.” It means our current tools don’t show obvious structural damage or inflammation, even when your symptoms are intense.

Think of your gut like a highway. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or celiac disease, the road is physically damaged: potholes, cracks, missing chunks. Blood tests, stool markers, and scopes can see that damage. In IBS, the road looks okay, but the traffic lights are mis-timed, the speed limits change randomly, and the drivers are overly jumpy. Function is off, structure looks “normal.”

Most lab tests in an IBS workup are not “IBS tests.” They’re exclusion tests. They’re designed to rule out:

- Hidden inflammation (like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis) - Celiac disease - Serious infections - Metabolic issues (thyroid, anemia, electrolyte problems)

So when labs are “normal,” what they really say is: “We don’t see evidence of structural damage, major inflammation, or a classic organic disease that explains this.”

They do not say: “We know exactly what’s wrong with your gut and how to fix it.”

That gap between what labs show and what you feel is where IBS lives.

Clinical Reality: How This Plays Out in Real Life

Here’s the pattern I see over and over in clinic.

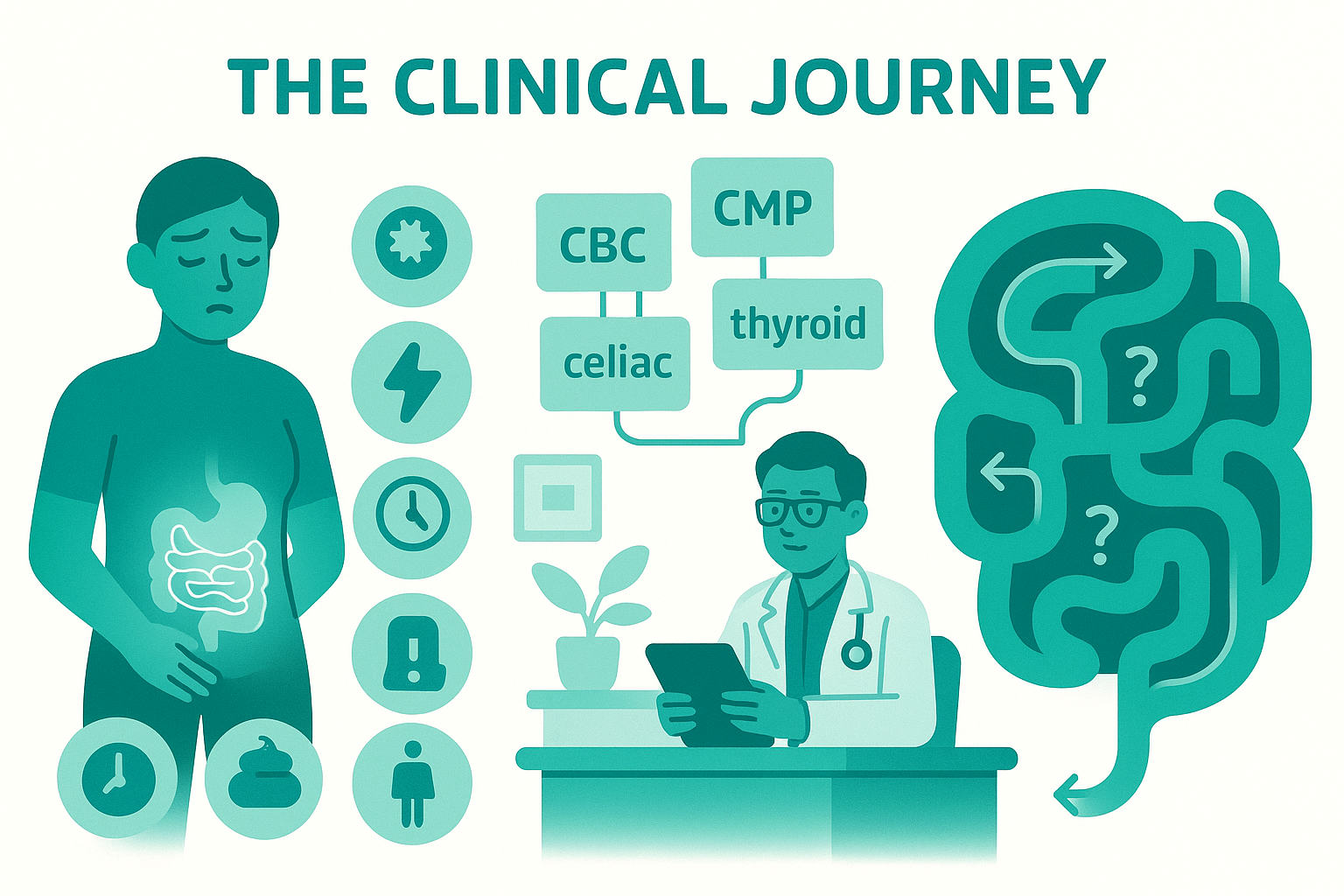

You have bloating, pain, diarrhea or constipation (or both), maybe mucus in the stool, maybe urgency that makes you map bathrooms everywhere you go. You finally see a doctor. They order some labs: CBC, CMP, maybe thyroid, maybe celiac antibodies. If diarrhea is a big feature, maybe a stool test for infection, sometimes fecal calprotectin (an inflammation marker).

Everything comes back normal or “borderline.” You’re told it’s IBS. You walk out with a handout and maybe a vague suggestion to “eat more fiber” or “reduce stress.” You try that, and either nothing changes or fiber makes you worse. Now you’re not just uncomfortable, you’re confused and a little angry.

Here’s why conventional advice often falls flat:

- Normal labs don’t measure gut sensitivity. You can have a colon that looks pristine on colonoscopy and still feel every gas bubble like a knife. That’s visceral hypersensitivity. No standard blood test captures it.

- Normal labs don’t measure motility patterns. Whether your colon is sluggish, overactive, or alternating between the two is about nerve-muscle coordination, not visible damage.

- Normal labs don’t capture microbiome nuance. Standard stool tests look for pathogens and sometimes inflammation, not the complex ecosystem shifts that can drive gas and bloating. Most commercial “microbiome” tests sold directly to consumers are way ahead of the science and not clinically actionable yet.

So you end up in this weird limbo: not “sick enough” on paper, but very symptomatic in real life.

That’s frustrating, and it’s valid. The system is built to catch cancer, severe inflammation, and infection first (which is good), but it’s not great at explaining the day-to-day misery of IBS. Understanding what your labs are actually ruling out is the first step to making peace with them—and then moving forward in a more targeted way.

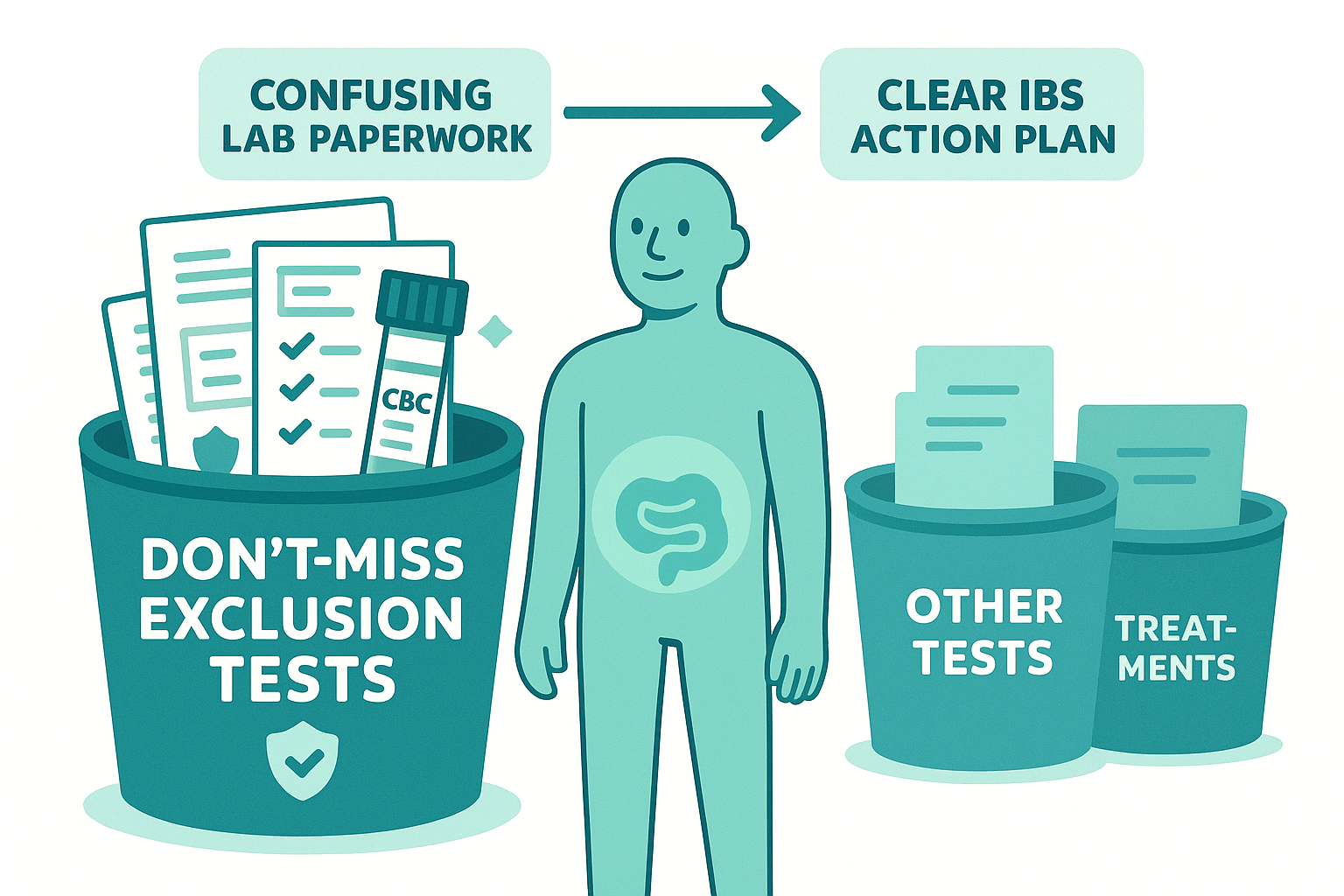

A Practical Framework: Making Sense of Your IBS Lab Work

Let’s turn this from mysterious paperwork into something you can actually use.

Think of labs in IBS in three buckets:

1. The “don’t-miss” exclusion tests

These are the ones that matter to be sure we’re not calling something IBS when it’s actually more serious:

- Basic blood work: CBC (anemia, infection clues), CMP (electrolytes, liver, kidney), maybe CRP or ESR (inflammation markers). - Celiac screening: usually tissue transglutaminase IgA plus total IgA. - Thyroid tests: TSH, sometimes free T4, because both overactive and underactive thyroid can mimic IBS. - Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin: stool markers of intestinal inflammation that help distinguish IBS from IBD. - Stool cultures or PCR panels if there’s ongoing diarrhea, blood, or recent travel.

If these are normal and your story fits IBS, that’s meaningful. It doesn’t fix your symptoms, but it does make things like IBD, celiac, and some infections much less likely.

2. The “sometimes helpful” tests

These depend on your specific pattern:

- Bile acid diarrhea tests (like SeHCAT in some countries, or indirect markers): useful if you have chronic watery diarrhea, especially after gallbladder removal. - Breath tests for lactose intolerance or, in selected cases, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO): helpful when symptoms are clearly triggered by certain carbs, but results are often messy to interpret and overused. - Pancreatic function tests if there’s weight loss, greasy stools, or clear malabsorption.

These aren’t routine for every IBS patient. They’re guided by your history, red flags, and response (or non-response) to basic strategies.

3. The “looks scientific but doesn’t help” category

This is where a lot of money gets wasted:

- Broad “food sensitivity” panels based on IgG antibodies - Most commercial microbiome mapping tests marketed directly to consumers - Random hormone panels without a clear clinical question

The evidence that these change outcomes in IBS is very weak. They create anxiety and restriction more than clarity. If someone is selling you a thousand-dollar panel as the “missing link” for your IBS, step back.

How to Use Your Labs as a Tool, Not a Verdict

Here’s a more useful way to relate to your test results:

First, separate two questions in your mind:

1. Have we reasonably ruled out the big, structural diseases? 2. Given that, what’s driving my symptoms functionally—motility, sensitivity, fermentation, or bile acid issues?

Labs mainly help with question one. For question two, you need pattern tracking, not more blood draws.

Start watching:

- Symptom timing: Do pain and bloating spike 30–90 minutes after meals (fermentation, rapid transit) or much later (slow transit, constipation)? - Stool pattern: Consistently loose, consistently hard, or alternating? Urgency? Incomplete evacuation? - Food relationships: Clear triggers with large doses of lactose, wheat, onions/garlic, beans, or is it more random? - Non-gut factors: Sleep, menstrual cycle, medications, recent infections.

Now line that up with what your labs have already ruled out.

Example: Your calprotectin is normal, celiac screen is negative, basic labs are fine. You have loose stools with urgency, especially in the morning and after meals. No weight loss, no blood. That pattern plus normal labs points away from IBD and toward IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant), possibly with a bile acid or motility component.

Different example: Normal labs, but constipation, hard stools, straining, and bloating that builds through the day. That’s more IBS-C (constipation-predominant) with a motility and gas-handling issue, not inflammation.

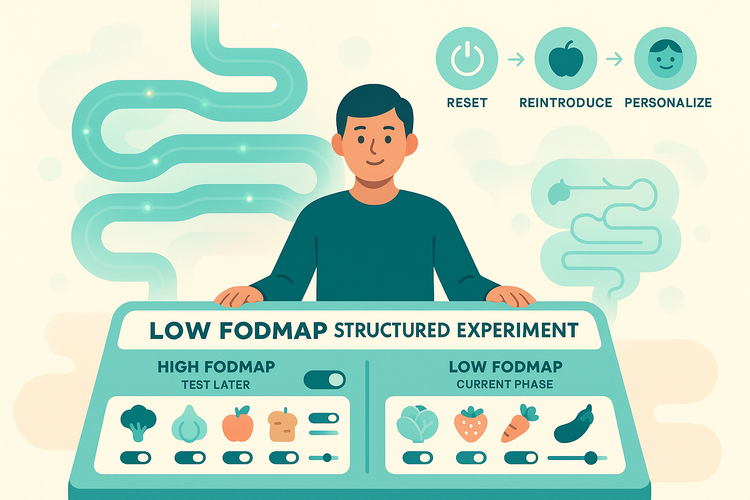

In both cases, chasing more normal labs isn’t helpful. The next steps live in tailored diet experiments (with clear hypotheses, not random restriction), targeted meds when appropriate, and nervous system-focused strategies for pain and urgency.

The key is this: normal labs shift the question from “What disease am I missing?” to “How is my gut functioning differently, and how do I work with that?”

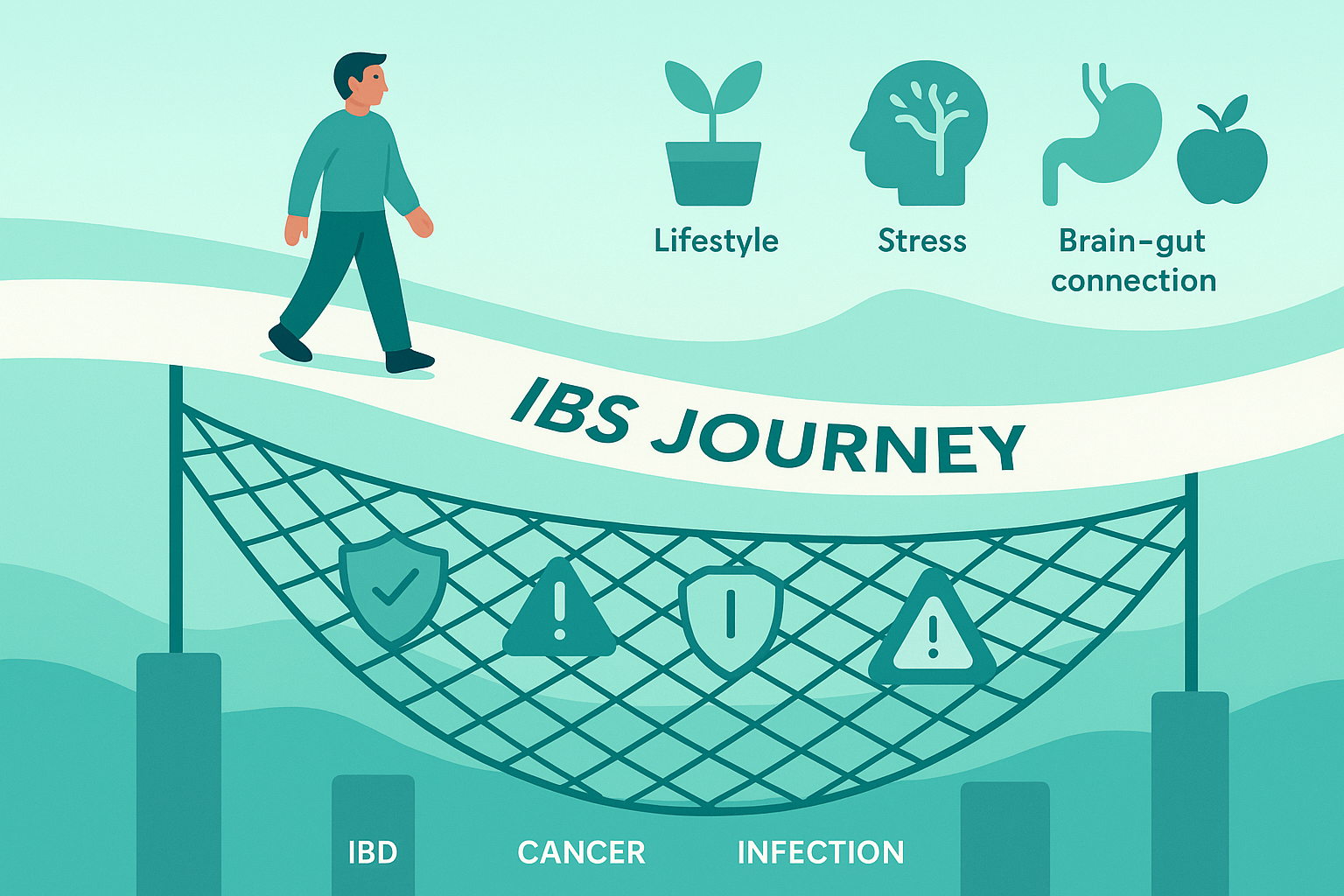

Closing: The Real Takeaway on IBS and Lab Tests

IBS isn’t “nothing wrong.” It’s “nothing obvious on the tests we currently have.” Your labs are doing an important job: they’re the safety net making sure we’re not ignoring celiac, IBD, cancer, or infection while calling it IBS.

Once that net is in place, the work changes. It becomes less about hunting for the perfect lab and more about understanding your own pattern—motility, sensitivity, fermentation, bile acids—and experimenting from there in a structured way.

Next time, we’ll dig into how to read your own symptom patterns like a clinician reads a chart, so your lived experience carries as much weight as your lab printout.