The Hidden Problem: IBS with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

The Hidden Problem IBS With Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Download this comprehensive checklist to bring to your next GI appointment. Get evidence-based answers and a clear action plan.

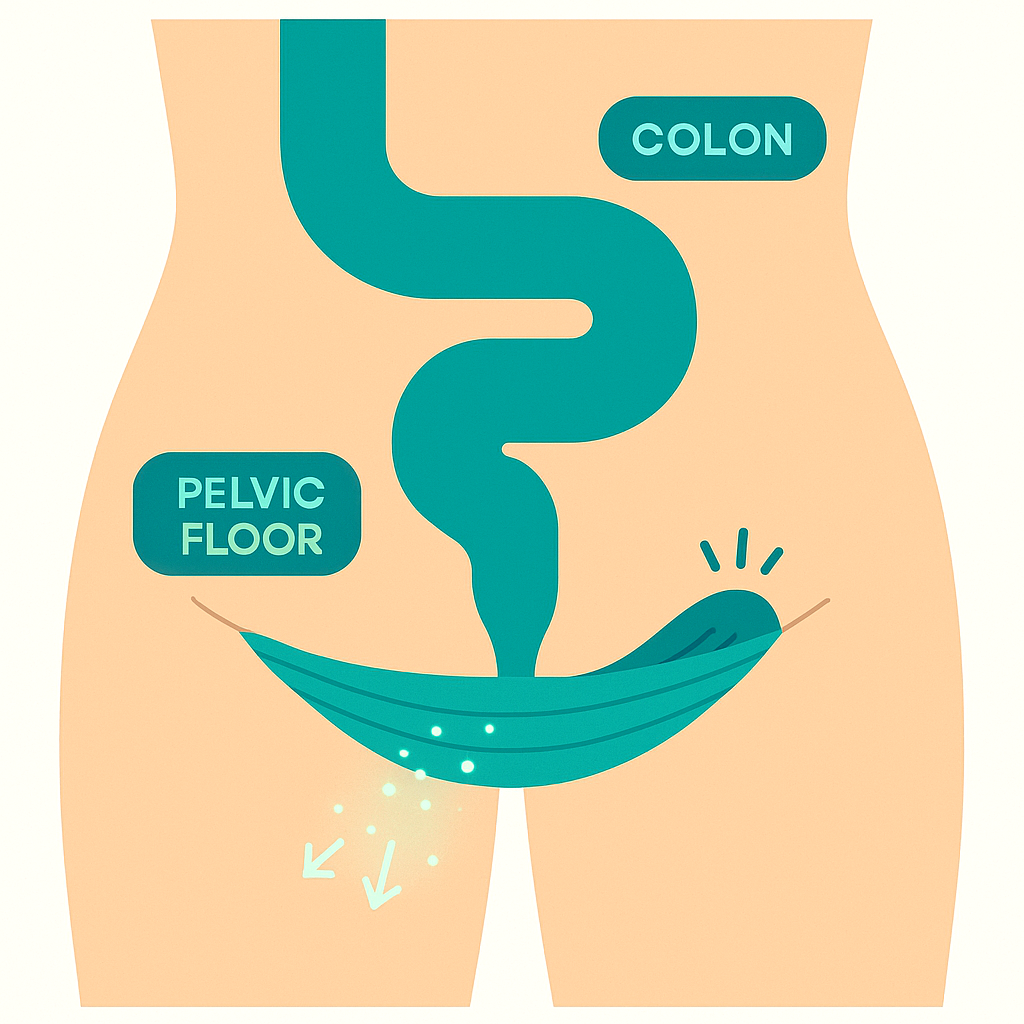

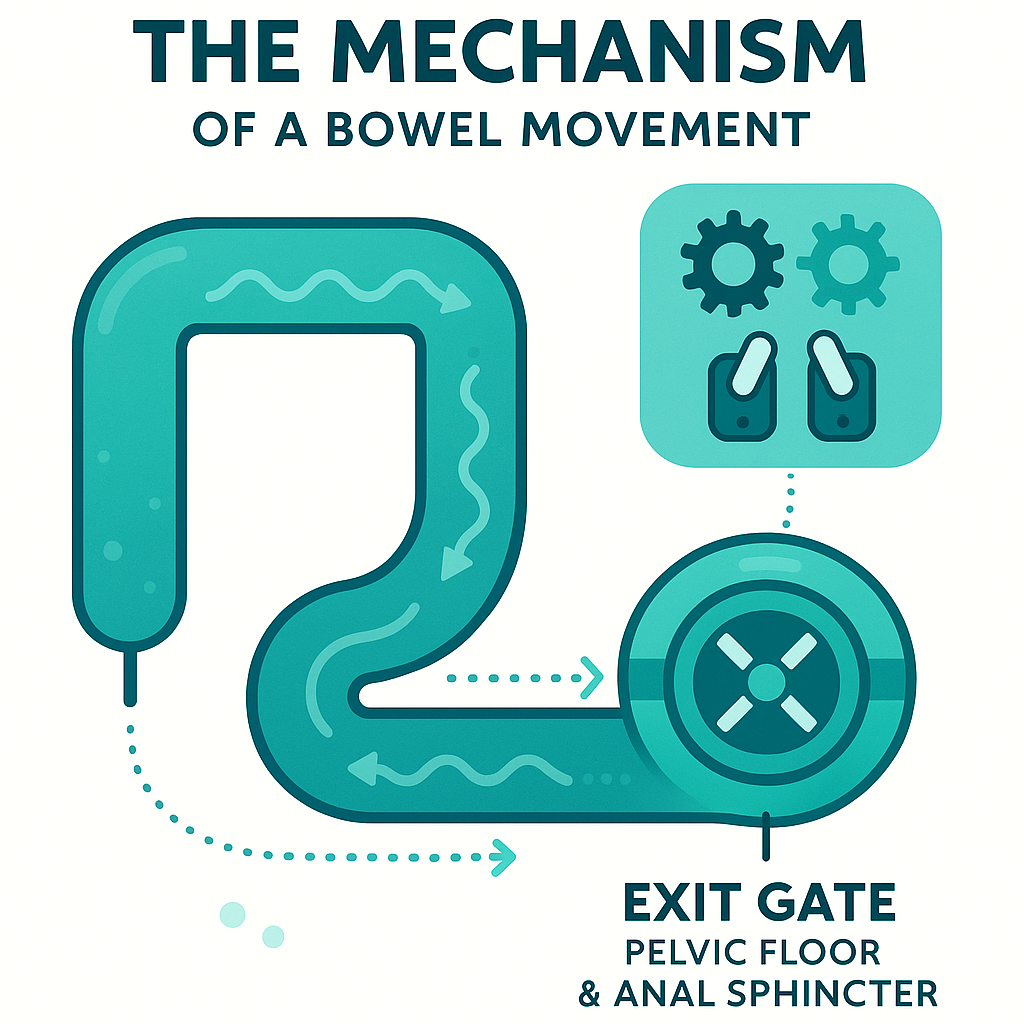

📥 Download PDF Checklist →Think of your gut like plumbing with a gate at the end.

Your colon moves stool along with rhythmic contractions. That part gets most of the attention. But at the very end, there’s the pelvic floor and anal sphincter, your “exit gate.” To poop, two things have to happen together: the colon has to push, and the pelvic floor has to relax and open.

In pelvic floor dysfunction, especially something called dyssynergic defecation, the timing is off. Instead of relaxing when you bear down, those muscles tighten or just don’t let go. It’s like trying to squeeze toothpaste out while someone pinches the nozzle shut.

Your brain experiences that mismatch as: “I need to go” + “I can’t go” + “this hurts” + “I’m still not empty.”

Over time, this creates a feedback loop. The colon starts to stretch from backed-up stool. Nerves in the rectum and colon become more sensitive. Gas and normal stool volume suddenly feel like “a brick in my pelvis.” Add IBS-level sensitivity and motility changes on top of that, and you get the perfect storm: bloating, pain, constipation, sometimes alternating with diarrhea when some stool sneaks around the blockage.

Clinical Reality

Here’s what this looks like in actual humans, not textbook diagrams.

You sit on the toilet, you feel the urge, you push—and nothing. Or a tiny bit. You know there’s more in there, but it just…won’t…come. You get off the toilet feeling half-finished, heavy, and uncomfortably full. You might go back several times a day for “incomplete” trips.

People describe needing to twist, lean forward, push on their abdomen, or even press around the vagina or perineum to get things moving. Some use their fingers to help stool out. That’s not “being dramatic.” That’s classic pelvic floor dysfunction.

Then there’s the IBS overlay. Maybe you were told you have IBS‑C or IBS‑M because you have pain, bloating, constipation, and sometimes looser stools. You were told to “eat more fiber” and “drink more water.” So you did. And you got more bloated, more uncomfortable, and still couldn’t fully empty.

This is where frustration sets in. You’re doing what you were told. You’re following “gut health” advice on the internet. You’re on osmotic laxatives, maybe stimulant laxatives, maybe probiotics. But if the exit gate is malfunctioning, pushing more water and fiber into the system just expands the traffic jam.

So you start to think: maybe it’s all in my head. It’s not.

A Practical Framework

This isn’t about slapping on another label. It’s about asking: “Is my problem moving stool through the colon, or getting it out?”

Start with pattern-watching.

Pay attention to what the actual experience of pooping is like. Not just how often, but how it feels. Do you need to strain for a long time? Does the urge come but disappear if you can’t get to a toilet right away? Do you feel blocked low down, like something is stuck right at the exit? Do you often feel “not done” even if you went?

IBS-related constipation from slow colon motility feels more like: no urge for days, then a big, hard stool, often with more generalized abdominal discomfort. Pelvic floor dysfunction tends to feel like: urge present, effort high, output disappointing, lots of time in the bathroom, and a sense of obstruction or incomplete emptying.

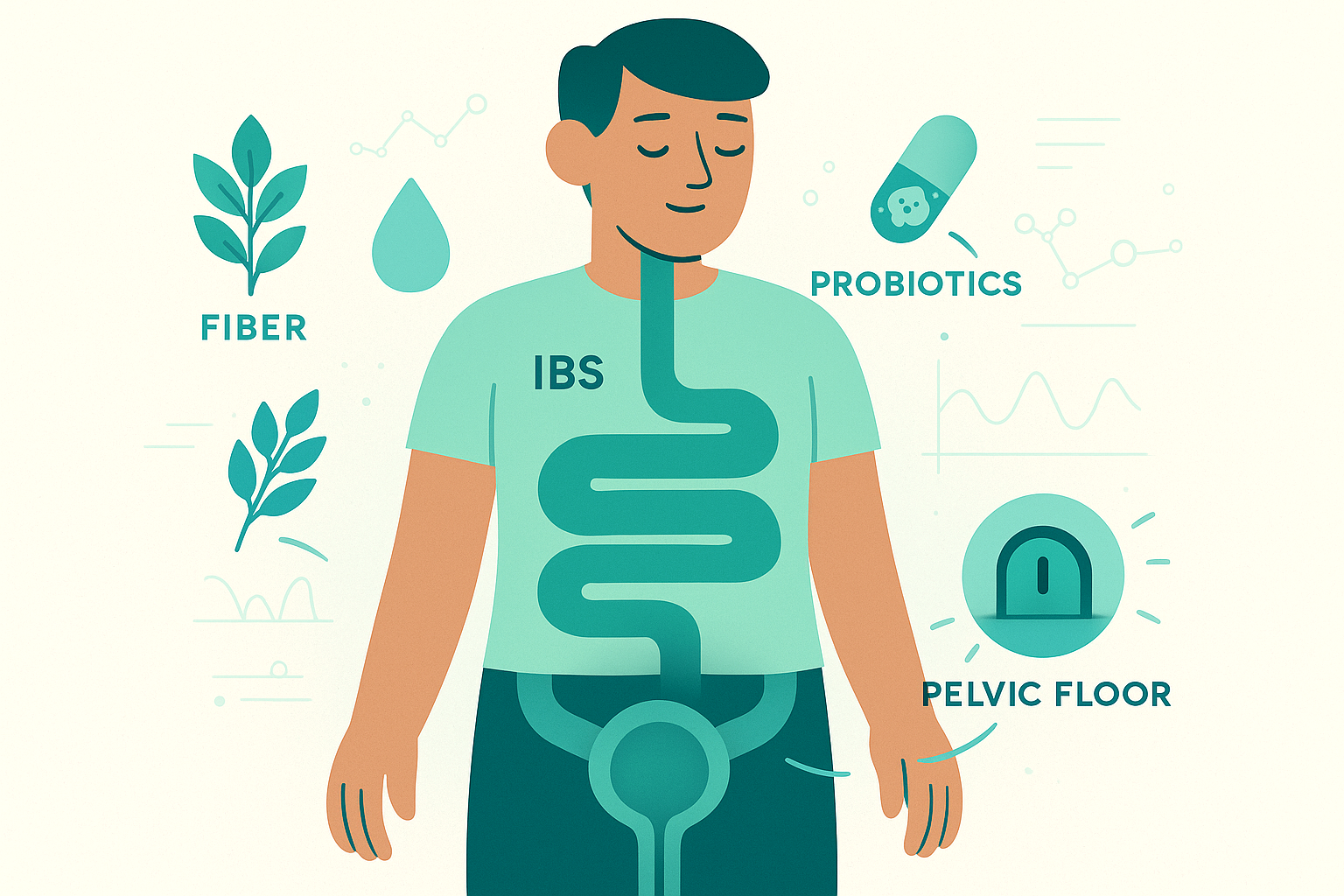

Here’s the key: pelvic floor-driven constipation is mechanical and trainable.

The best-evidence treatment isn’t a supplement. It’s pelvic floor physical therapy with biofeedback. That’s a specialized therapist teaching you, often with gentle sensors and visual feedback, how to coordinate those muscles—how to relax at the right moment, how to bear down without squeezing the exit shut, how to break the pain–tension–constipation cycle.

For IBS patients, this doesn’t magically fix everything, because you may still have visceral hypersensitivity and motility quirks. But if the outlet problem is reduced, your colon isn’t constantly overfilled and stretched, and your nerves aren’t screaming from mechanical strain. That alone can lower pain and bloating significantly.

While you’re figuring this out, keep a symptom log that notes:

- Time of bowel movements - How much effort you needed - Whether you felt fully empty - Any positions or tricks that help or make it worse

You’re not doing this to impress a doctor with a spreadsheet. You’re doing it to spot patterns that scream “pelvic floor” instead of “just IBS.”

If your notes consistently show strong urges with poor emptying, long straining, or needing manual help, that’s not solved with another gut reset or elimination diet. That’s a pelvic floor issue until proven otherwise.

Closing

The big takeaway: not all constipation in IBS is a colon problem. Sometimes the colon is trying its best, and the pelvic floor is the bottleneck. When that’s the case, more fiber, more water, and more supplements just build a bigger backlog.

Once you start seeing your symptoms through the lens of “plumbing plus gate,” a lot of confusing IBS misery starts to make sense. In the next piece, we’ll dig into how pelvic floor assessment actually works, and what good therapy looks like in real life - not just on a clinic brochure.