Post-Infectious IBS: When a Stomach Bug Rewires Your Gut

Post Infectious IBS When A Stomach Bug Rewires Your Gut

Download this comprehensive checklist to bring to your next GI appointment. Get evidence-based answers and a clear action plan.

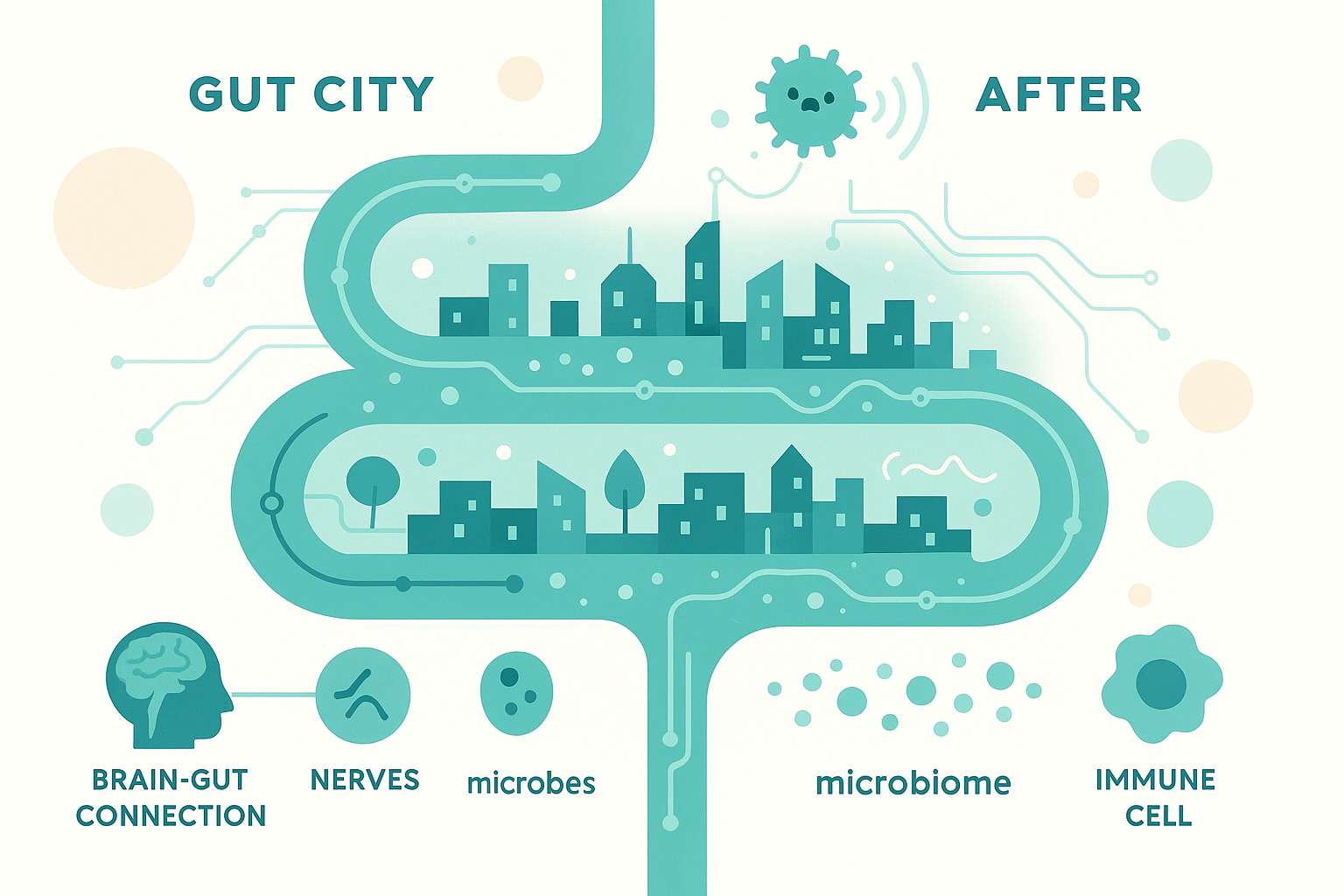

📥 Download PDF Checklist →Think of your gut as a crowded city with electricity, plumbing, traffic lights, and a police force.

Before the infection, the city functioned. Maybe not perfectly, but you could live there.

Then you got hit with an invasion: bacteria, virus, or parasite.

During that infection, your immune system did its job. It sent inflammatory cells into the gut lining, cranked up immune signals, and flushed everything out with rapid motility. That’s the “I lived in the bathroom for 48 hours” part.

For most people, once the invader is gone, the city rebuilds. The traffic lights (nerves), plumbing (motility), and police (immune cells) reset.

In post-infectious IBS, the reset is glitchy.

The infection can damage tiny nerve fibers in the gut wall and the cells that coordinate muscle contractions. You end up with disordered motility: segments of bowel that spasm, others that move too slowly, and timing that’s off.

At the same time, the immune system sometimes keeps a low-grade, smoldering activation in the gut lining. Not the kind of inflammation we see in Crohn’s or colitis, but enough to change sensitivity and movement.

Add in another twist: your brain–gut connection can become “sensitized.” Signals from the gut get turned up in the spinal cord and brain. Normal gas or stretching that used to be background noise now registers as pain, urgency, or bloating.

So no, this isn’t “nothing.” It’s not “all in your head.” It’s a rewired system after a real hit.

Clinical Reality

On your end, it usually has a clear origin story.

You remember the trip, the sketchy chicken, the norovirus that took out half your office, the antibiotic course that followed. Before that? You could eat pizza and salad and maybe get a bit gassy. After that? It’s like your gut has trust issues.

The patterns are surprisingly consistent.

You might notice loose stools for weeks or months that never fully normalize. Or a new bowel rhythm: multiple urgent morning trips, then nothing the rest of the day. Some people swing between diarrhea and constipation. Bloating becomes a main character, not a side note.

Certain foods start setting things off that never used to: high-FODMAP carbs, greasy food, large meals. Not because those foods suddenly turned “toxic,” but because a hypersensitive, irregularly moving gut handles them badly.

Then you get the standard advice: “Eat more fiber, relax, drink water.” For some with post-infectious IBS, more fiber means more gas in a cramped, twitchy system. You feel worse, not better. You’re told to avoid dairy, gluten, sugar, air, and joy. Nothing quite lines up.

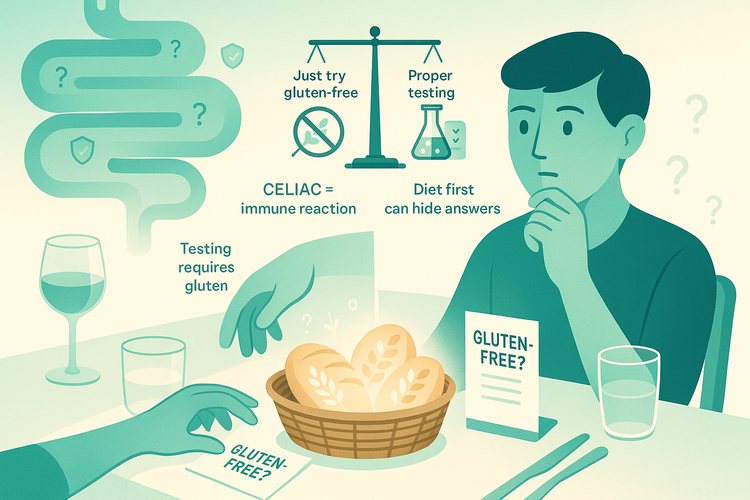

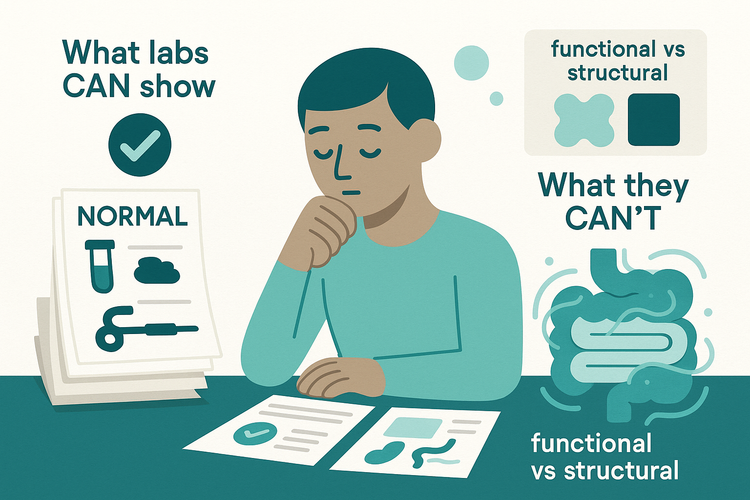

You feel dismissed because the colonoscopy, blood work, and stool tests come back “normal.”

What those tests are really saying is: no cancer, no IBD, no celiac, no overt infection. That’s good. But they don’t show the subtle nerve, motility, and low-grade immune changes that define post-infectious IBS. So you’re left with real symptoms and a normal workup, plus a vague label.

Frustrating is an understatement.

A Practical Framework

Instead of chasing magic foods or miracle supplements, it helps to see post-infectious IBS as three overlapping problems: sensitive wiring, awkward motility, and a touchy immune layer.

Your job isn’t to “fix everything at once.” It’s to learn your system well enough to stop poking the raw spots.

Start with patterns, not rules.

Track just a few things for 2–3 weeks: what you eat (broad categories, not calorie apps), timing of meals, stool pattern, pain/bloating, and context (sleep, illness, antibiotics, your period if you menstruate). Don’t aim to be perfect. You’re looking for repeatable patterns, not one-off flukes.

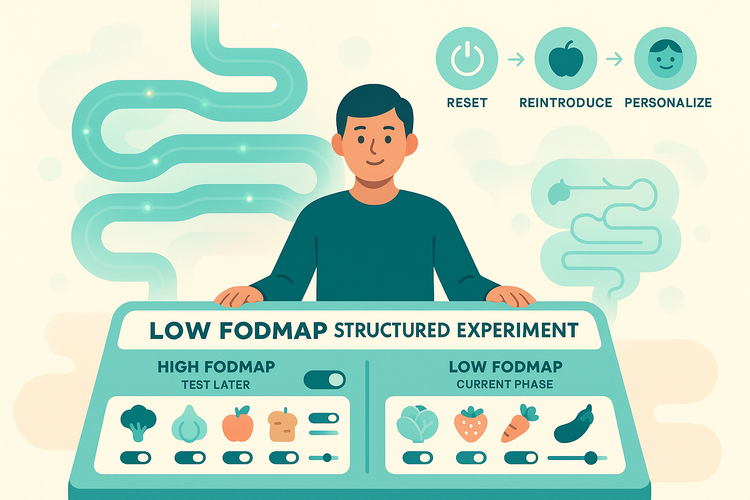

Notice if your gut hates large, late meals but tolerates smaller, earlier ones. That’s motility. Notice if specific carb-heavy foods (onions, apples, wheat, beans) reproducibly lead to gas and urgency 4–8 hours later. That’s fermentation on a hypersensitive background, not “toxins.”

If you clearly link high-FODMAP foods to symptoms, a temporary, structured low-FODMAP trial (done properly, with reintroduction) can help identify your personal irritants. This is about turning the volume down so you can see the wiring, not living on five “safe” foods forever.

On the immune side, post-infectious IBS tends to settle over months to a few years, but not always on its own. Some people benefit from gut-directed medications (for motility or bile acids), low-dose neuromodulators that calm nerve signaling, or targeted probiotics with real data in post-infectious cases. This is where a clinician who actually understands IBS—not just rules it out—can be useful.

And then there’s the brain–gut piece. Symptoms themselves can train your nervous system to stay on high alert. That doesn’t mean “it’s psychological.” It means your pain system learned a pattern. Gut-directed hypnotherapy and cognitive approaches aren’t about blaming you; they’re about retraining the signal processing so every bubble of gas doesn’t trigger a five-alarm fire.

The through-line: experiment, observe, adjust.

Rigid plans usually backfire. Curiosity paired with structure—“When X, my gut does Y”—is far more powerful over time than any single “IBS diet.”

CLOSING

Post-infectious IBS is not a character flaw or a vague stress reaction. It’s what can happen when a real infection leaves your gut’s wiring, movement, and immune tone slightly off-kilter.

You can’t rewind the infection, but you can understand the new rules your gut is playing by. Next time, we’ll dig into how to tell post-infectious IBS apart from other IBS subtypes—and why that distinction actually changes what’s worth trying.