IBS vs SIBO - How to Tell the Difference Without Guessing

IBS Vs SIBO How To Tell The Difference Without Guessing

Download this comprehensive checklist to bring to your next GI appointment. Get evidence-based answers and a clear action plan.

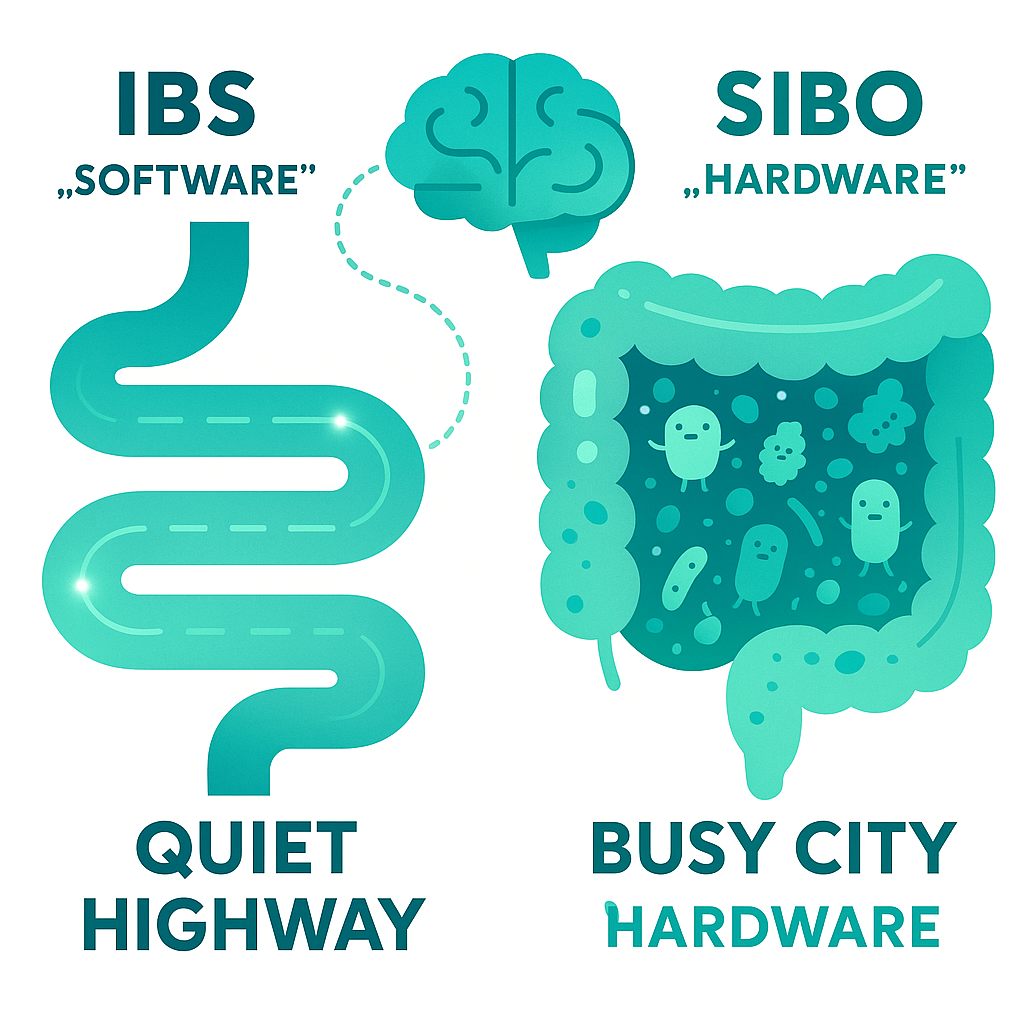

📥 Download PDF Checklist →Think of your small intestine as a quiet highway and your colon as a busy city.

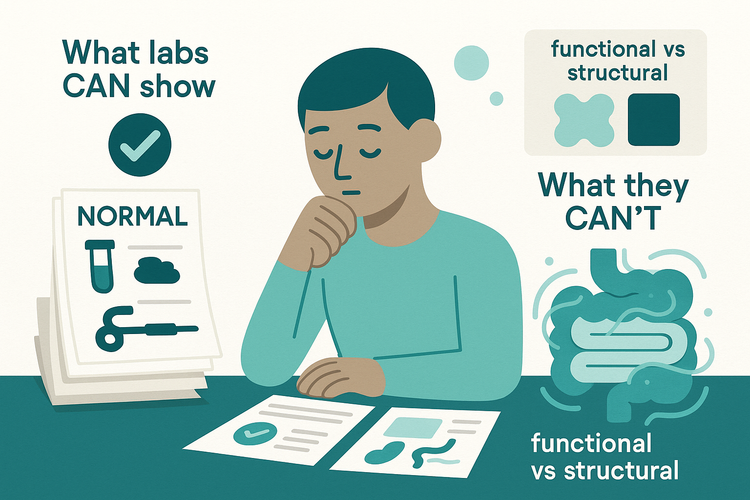

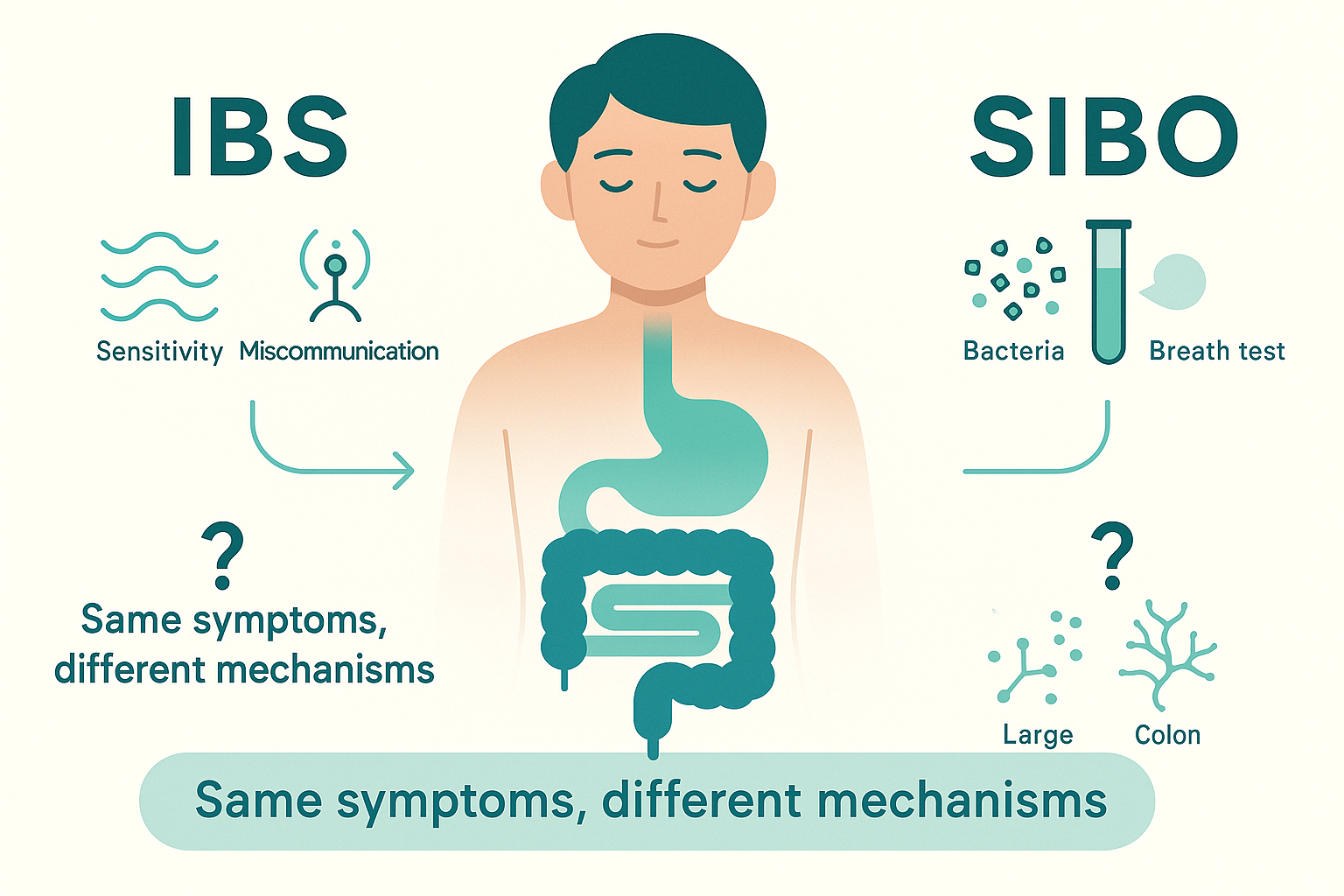

IBS is mostly a how your gut behaves problem: how fast it moves, how sensitive the nerves are, how your brain and gut talk to each other. The structure is usually normal. The “software” is glitchy.

SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) is more of a where the bacteria are problem. You’re supposed to have very few bacteria in the small intestine and a ton in the colon. With SIBO, too many “city bacteria” migrate onto the quiet highway.

That location shift matters.

When bacteria show up early, they ferment carbs too soon. They make gas in the wrong place. The small intestine isn’t designed to stretch that much, so even normal amounts of gas can feel like knives.

But here’s the twist: IBS and SIBO overlap. IBS can slow or speed motility. Slower motility can let bacteria hang around and overgrow. Faster motility can flush them out. So IBS patterns can set the stage for SIBO, and SIBO can then amplify IBS symptoms.

IBS = disordered motility and sensitivity. SIBO = misplaced bacteria in the small intestine. In real life, many people have elements of both.

Clinical Reality: How This Shows Up in Your Life

On paper, textbooks split IBS and SIBO cleanly. In your body, it’s messy.

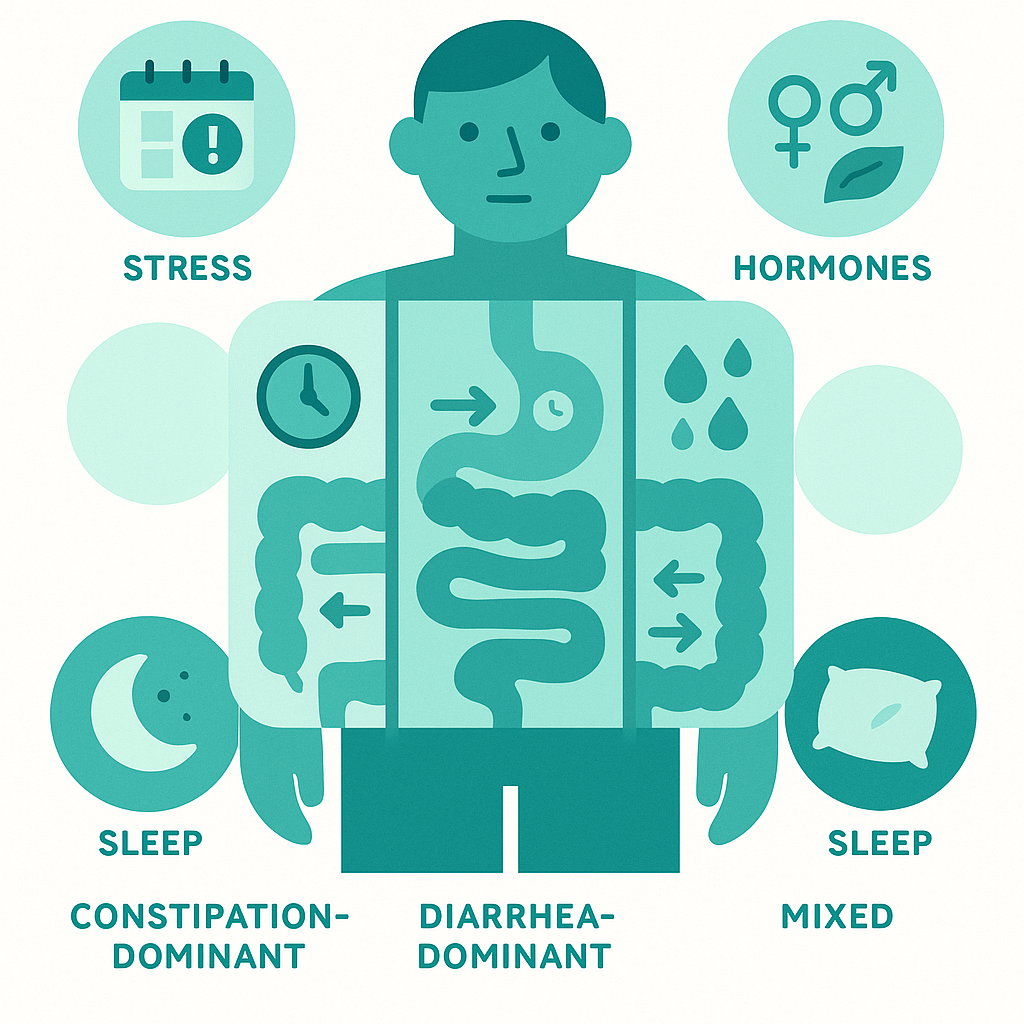

IBS tends to have a stable personality over time. You’re a constipation-dominant person, or diarrhea-dominant, or you swing between the two. The pattern has probably been there for months or years. Stress, hormones, sleep, and food volume change the intensity, but your “baseline wiring” feels familiar.

SIBO tends to feel more like something piled on top of your baseline. Gas comes earlier after eating. Bloating can be extreme, like “I look six months pregnant by 3 pm.” You might notice a very specific trigger window: symptoms ramping up 30–90 minutes after meals, before food would normally reach the colon.

People with more SIBO-type physiology often say things like: “I burp and bloat shortly after eating even small meals.”, “FODMAPs wreck me fast, not just many hours later.”, “Antibiotics for something else accidentally improved my gut for a bit.”

People with more pure IBS physiology often describe: A strong link to gut speed: either always slow, always fast, or swinging, Symptoms that flare with stress, sleep loss, or menstrual cycle, even when food is the same, Bloating that’s real and uncomfortable, but not always meal-timed in a neat way.

Conventional advice often fails because it assumes you’re only one thing. Low FODMAP helps some IBS features but not the motility piece. A single course of rifaximin helps some SIBO-ish features but not the underlying IBS wiring. So you get partial relief, then feel like a failure when symptoms come back.

You’re not failing. The model was too simple.

Practical Framework: Not Guessing, Actually Observing

Here’s how I walk patients through this in clinic without turning it into “is it IBS or SIBO?” drama.

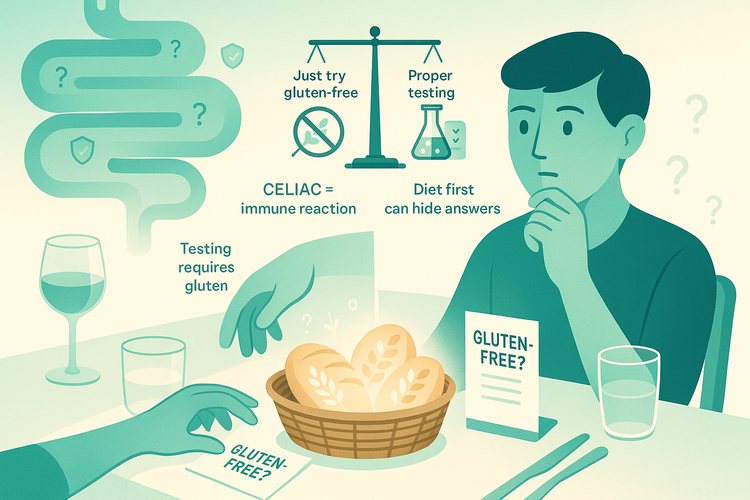

First, assume IBS is the base layer if: You’ve had symptoms for more than 6 months. Standard labs, celiac testing, and basic imaging are normal. Your main issues are stool form, urgency, and bloating.

Then ask: does anything on top of that look like misplaced bacteria?

Look at timing. For a week, write down: What time you eat. When gas, bloating, or pain start. When your bowel movements happen.

If your worst gas and bloating reliably hit in the first 1–2 hours after meals, that leans more toward small-bowel involvement (SIBO-ish). If symptoms are more about later-in-the-day fullness, evening distension, and bowel movement patterns the next morning, that’s more classic IBS rhythm.

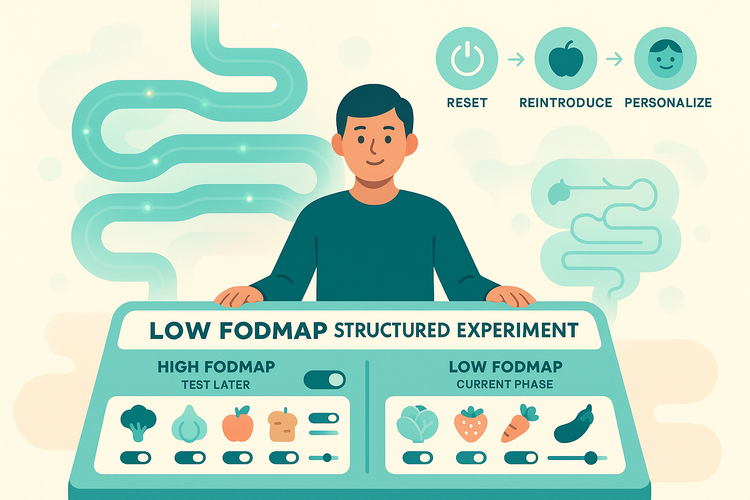

Next, look at triggers. Do carb-heavy meals (especially things like onions, garlic, wheat, beans) cause early symptoms that feel explosive and upper-abdominal? That’s more consistent with bacteria fermenting too soon. If triggers are broader, big meals, fatty foods, stress, regardless of the carb type, that’s more motility/sensitivity.

Then, look at antibiotic clues. This is not a recommendation to “try antibiotics and see.” But if you’ve had antibiotics for something else and you clearly remember, “My gut was weird but actually better for a couple of weeks,” that raises the odds that bacteria location was part of the story.

Finally, don’t let breath tests boss you around. Hydrogen/methane breath tests are imperfect. They can be falsely positive (fast transit, high colonic fermentation) or falsely negative (overgrowth in areas the test can’t “see”). They’re a piece of data, not a verdict.

The real framework is: IBS = chronic pattern of motility + sensitivity. SIBO = layer of misplaced bacteria that modifies that pattern.

So the goal isn’t “Do I have IBS or SIBO?” It’s “How much of my symptom load is wiring vs. bacteria vs. what I’m feeding them?”

From there, treatment can be more sequence-based: calm the system (bowel regularity, basic triggers), then decide if it’s worth chasing SIBO with testing or treatment, not the other way around.

Closing: The Takeaway

IBS and SIBO aren’t rival diagnoses fighting for your chart. IBS is the way your gut behaves; SIBO is one possible complicating factor. You don’t have to guess blindly or chase every protocol on the internet. With timing, patterns, and a bit of structured observation, you can get a much clearer picture of what’s driving your own symptoms.

Next time, we’ll dig into breath tests, why they confuse so many people, and when they’re actually worth doing.