IBS Isn't One Disease | Gut Check Daily Explains

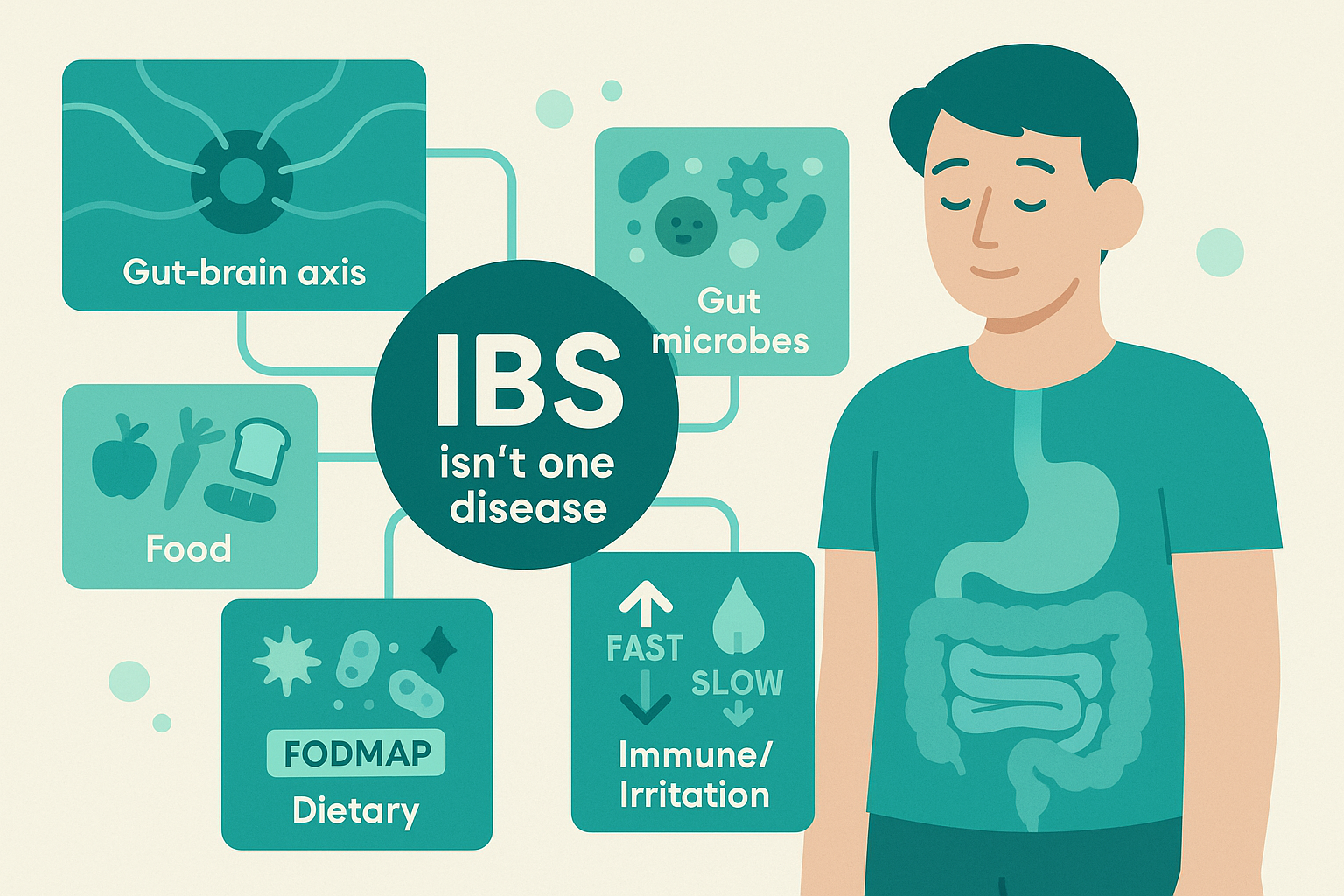

“IBS” describes symptoms, not a single disease.

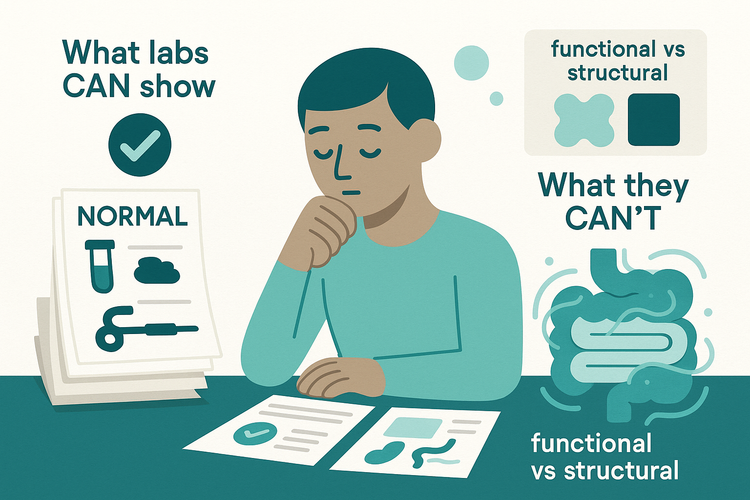

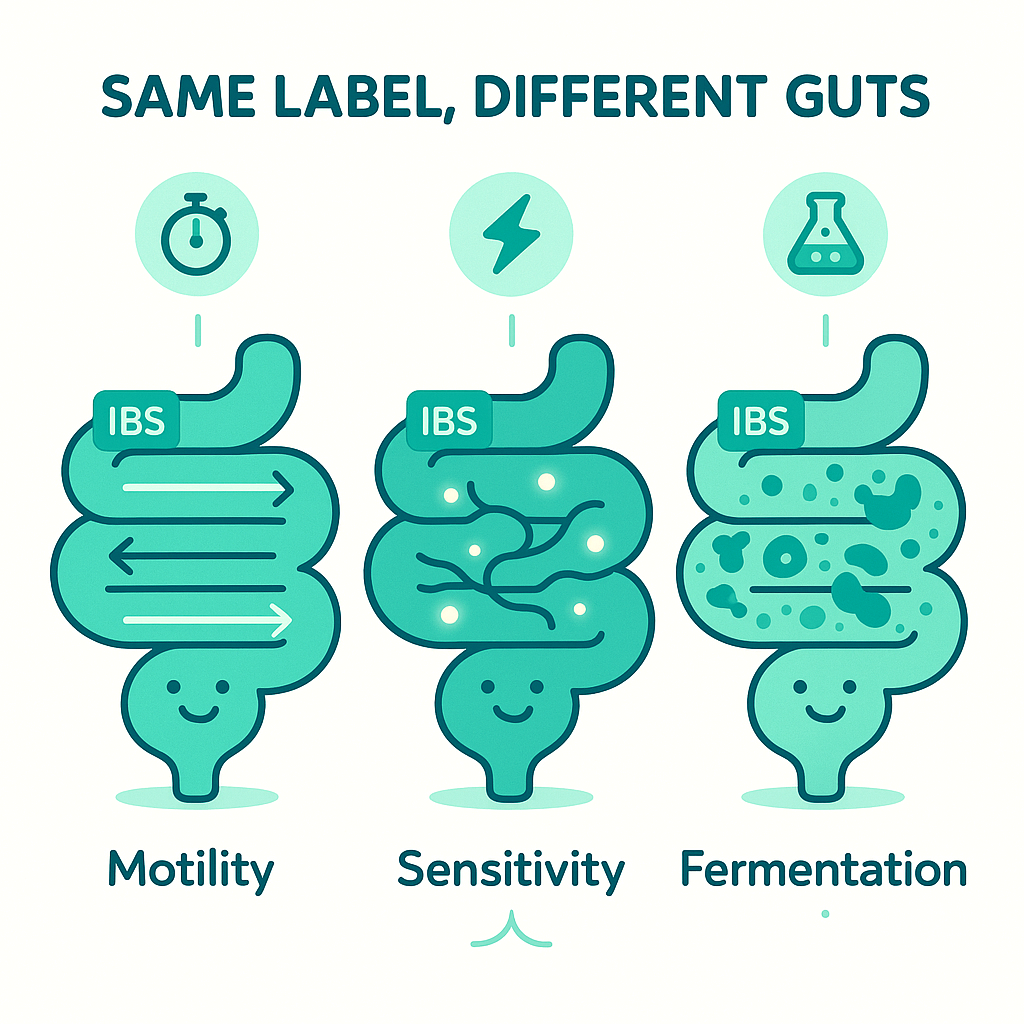

On paper, it’s abdominal pain plus a change in bowel habits, with no obvious structural damage. Under the surface, though, at least three big systems can be driving those symptoms: motility, sensitivity, and fermentation.

Motility is how fast or slow your gut moves. In some people, the colon behaves like a hyperactive washing machine on the spin cycle (IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant). In others, it’s like a sluggish conveyor belt (IBS-C, constipation-predominant). Some swing back and forth (IBS-M for mixed).

Sensitivity means the “volume knob” on your gut–brain connection is turned up. The intestines stretch with gas or stool the way they do in everyone, but your nerves send louder pain signals to the brain. Same amount of gas, very different experience.

Fermentation is all about your gut microbes and what you feed them. Bacteria ferment carbs you don’t fully absorb, producing gas and chemicals that can change motility and sensation. In one person, that’s a mild background process. In another, it’s a bloating-and-cramping bomb.

Most people with IBS have some combination of these. That’s why calling IBS “one disease” is like calling all engine problems “car syndrome.”

Clinical Reality: Why It Feels So Random

In real life, this shows up as maddening inconsistency.

You eat pasta one day and feel fine. Another day, same meal, and you’re doubled over with pain and rushing to the bathroom. You cut out gluten, then dairy, then coffee. Things improve for a week, then fall apart again. It feels chaotic, like your gut has a mind of its own.

Part of the chaos is that different mechanisms can dominate on different days. Sleep loss and anxiety can crank up visceral sensitivity, so what was tolerable yesterday suddenly hurts today. A viral bug, antibiotics, or a random foodborne infection can nudge your microbiome and fermentation patterns. Hormone shifts across your menstrual cycle can slow or speed motility.

Standard advice often fails because it assumes IBS is one thing. “Just add fiber” works if your main issue is slow transit constipation and you tolerate fermentation well. If your problem is hypersensitive nerves and bacterial over-fermentation, more fiber can feel like pouring gasoline on a fire.

Same with “just relax, it’s stress.” Yes, brain–gut signaling matters. But if your colon is propelling everything through at double speed or your microbes are churning out a ton of gas, no amount of deep breathing will magically neutralize that.

The frustration is real. You’re not “failing” at IBS management. You’re trying to use one-size-fits-all tips on a condition that isn’t one-size-anything.

Practical Framework: Think Subtypes, Not Rules

Instead of asking, “What’s the best IBS diet?” it’s more useful to ask, “Which pieces of IBS do I seem to have?”

Start with patterns, not bans. Over two weeks, jot down three things after each meal: what you ate, when symptoms hit, and what type they were (pain, bloating, urgency, constipation). You’re not looking for a perfect food list. You’re looking for repeating themes.

If your main pattern is urgency and loose stool, your motility dial is likely turned up. Caffeine, big fatty meals, and sudden large portions can all exaggerate that “rush through” effect. In that scenario, smaller, more evenly spaced meals and moderating stimulants is a targeted experiment, not a moral judgment about “bad foods.”

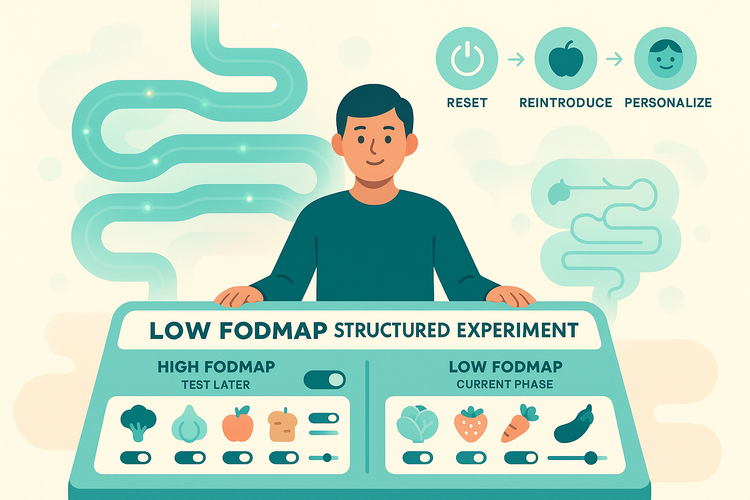

If your main pattern is bloating and distension that builds over the day, especially after onions, garlic, beans, apples, or wheat, fermentation is probably playing a big role. That’s where a structured trial of reducing FODMAP-heavy foods (with a plan to systematically reintroduce them) can give data, not permanent restriction. Most people don’t need a life-long ultra-low FODMAP diet.

If pain is the dominant symptom, even with fairly normal stools, visceral sensitivity is front and center. Here, focusing only on food creates a lot of stress without much payoff. Gut-directed hypnotherapy, certain neuromodulator medications, or specific brain–gut behavioral therapy have actual evidence for dialing down that pain volume knob.

Most people have overlaps. Mild constipation plus major sensitivity. Or moderate fermentation plus stress-triggered motility swings. That’s why your framework needs to be iterative: test one hypothesis at a time, give it a couple of weeks, keep what clearly helps, discard what doesn’t.

And through all of this, remember: the goal isn’t a perfect symptom-free life. It’s shifting from “my gut is random and terrifying” to “I understand the levers, and I know which ones are worth pulling.”

Closing: One Label, Many Pathways

IBS isn’t a single disease you fix with a single trick. It’s a cluster of overlapping pathways given one umbrella name because our tests can’t yet cleanly separate them. When you start thinking in terms of your mix of motility, sensitivity, and fermentation, your symptoms stop looking so mysterious.

In the next piece, we’ll dig deeper into one of those levers—motility—and why your colon’s speed setting matters more than you’ve been told.