The Complete IBS Guide: What Your GI Really Thinks But Doesn't Have Time To Say | Gut Check Daily

2025 11 25 The Complete IBS Guide What Your GI Really Thinks But Doesnt Have Time To Explain

Download this comprehensive checklist to bring to your next GI appointment. Get evidence-based answers and a clear action plan.

📥 Download PDF Checklist →If one more person tells you IBS is “just stress,” you’re going to scream. You’ve done the fiber, the probiotics, the food diary, the “try to relax” talk. You still don’t know why some days you’re fine and other days your gut behaves like it’s on a separate lease. This is the guide you should get in a GI office, but there’s never enough time between “so, how long have you had symptoms?” and “we’ll call you with your test results.”

1. What IBS Actually Is (And What It Definitely Isn’t)

IBS isn’t one disease. It’s a syndrome - a cluster of symptoms that happen together when the wiring, chemistry, and movement of your gut are out of sync.

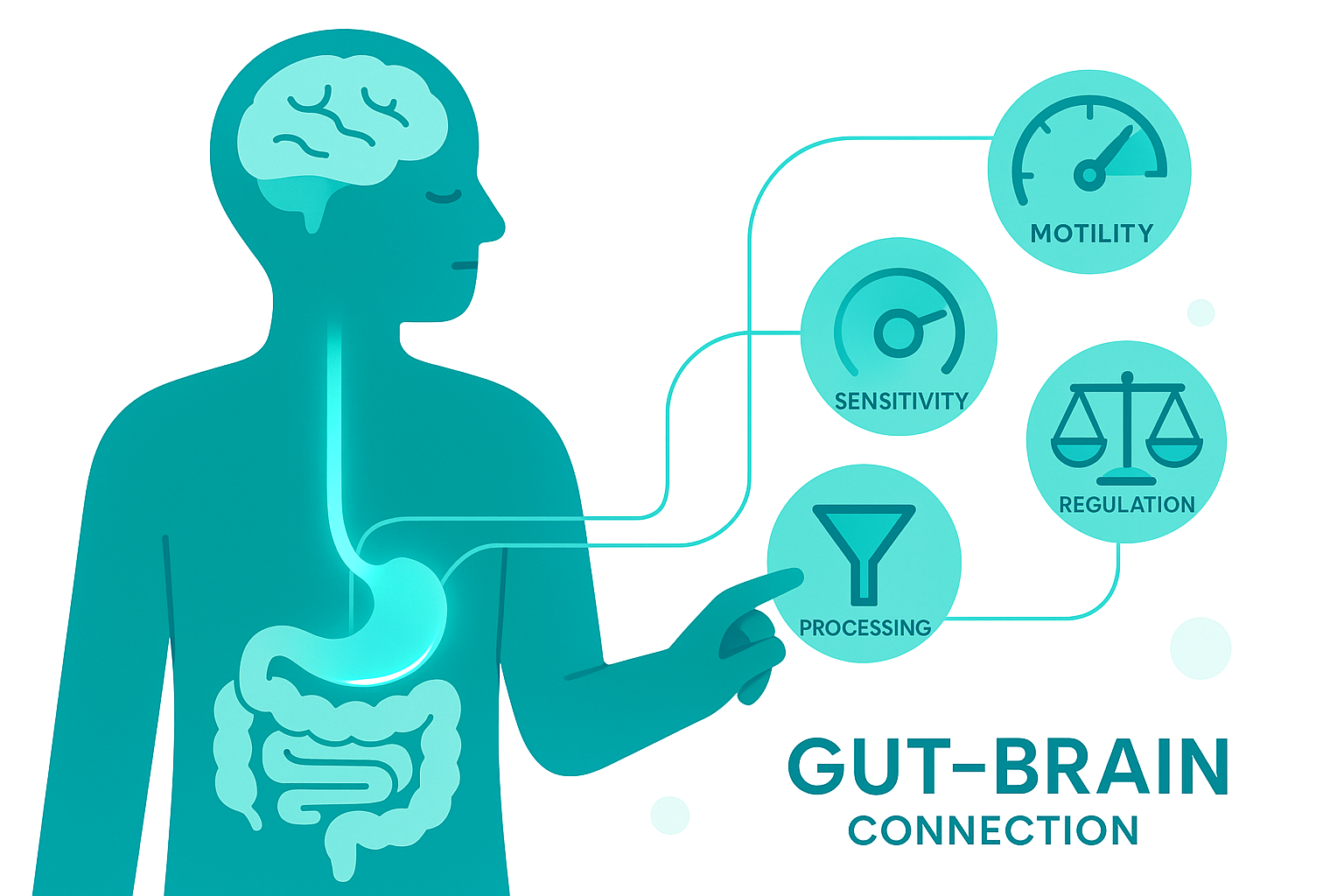

Think of your gut as a long, muscular tube with its own nervous system (the enteric nervous system). It coordinates three main jobs: Move things along (motility), Digest and absorb (enzymes, bile, transporters), Communicate with your brain (gut-brain axis)

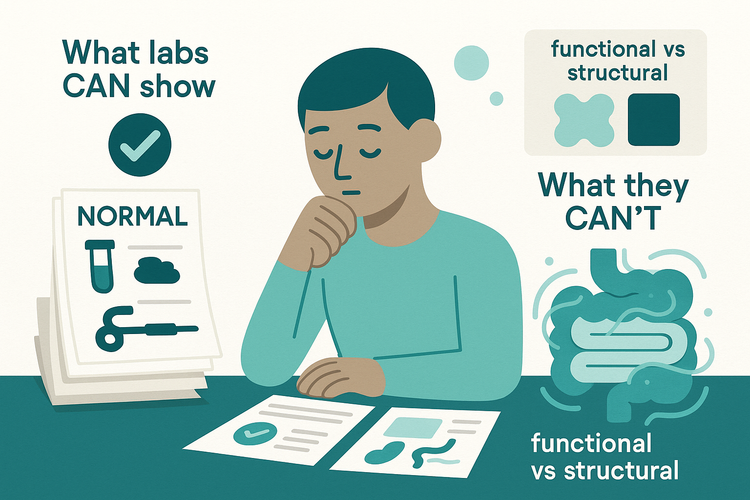

In IBS, those systems are still structurally intact. The colon isn’t inflamed like in Crohn’s. There aren’t ulcers like in peptic disease. Biopsies look normal. Blood tests are often normal. That’s why you keep hearing “everything looks fine.”

But functionally, several things go wrong:

1. Motility goes off-beat. The muscles of your intestines contract in waves to move food and waste. In IBS: Some people have too-fast transit (IBS-D): the colon pushes things through quickly, so water doesn’t get reabsorbed → loose stools. Others have too-slow transit (IBS-C): the colon holds onto stool too long, over-absorbs water → hard, difficult-to-pass stools. Many have mixed (IBS-M): the system alternates between overactive and sluggish.

Imagine a conveyor belt that randomly speeds up and slows down. That’s your gut.

2. The nerves are turned up too loud. The gut is covered in sensory nerves that report stretching, gas, and movement to the brain. In IBS, those nerves become hypersensitive. The same amount of gas or stool that wouldn’t bother someone else feels like pressure, cramping, or sharp pain to you.

Nothing is “blocking” the intestine. But the signals are amplified. This is called visceral hypersensitivity.

3. The gut–brain communication is glitchy. Your brain and gut are constantly talking via nerves, hormones, and immune signals. Stress, poor sleep, past infections, early life experiences - all of these can recalibrate that system.

Over time, the brain can start to: Expect pain, Pay more attention to gut sensations, Interpret normal signals as threatening.

You’re not imagining it. But your brain is absolutely involved, not as the cause, but as part of a feedback loop.

4. The microbiome and immune system are slightly off. This is where the internet goes wild with theories. Here’s what we actually know: Some people develop IBS after a nasty GI infection (post-infectious IBS). There are subtle changes in gut bacteria and low-grade immune activation in some IBS patients. These changes can affect gas production, motility, and nerve sensitivity.

What we don’t have is a single “bad bug” or a universal “IBS microbiome pattern.” Anyone selling you a microbiome “cure” is oversimplifying a very complex system.

So IBS is: Real. Functional (about how it works, not how it looks). Multifactorial (motility, nerves, brain, microbiome, immune system)

And no, it’s not “in your head.” It’s in your gut-brain wiring.

2. How IBS Shows Up in Real Life (And Why Standard Advice Fails)

In clinic, IBS rarely walks in as “I have IBS.” It walks in as:

“My stomach blows up like a balloon by afternoon.”

“I have to know where every bathroom is.”

“I look 6 months pregnant by the end of the day.”

“I either can’t go for three days or I can’t get off the toilet.”

The patterns are surprisingly consistent.

The classic daily arc is Morning: You wake up relatively flat. Maybe mild discomfort, but manageable. After breakfast: Things start to move. Some people get an urgent bowel movement soon after eating (gastrocolic reflex is exaggerated in IBS-D). Midday to afternoon: Bloating builds, especially if you’re sitting a lot or eating large meals. Evening: Max distension, heaviness, gassiness. You feel huge, but your weight hasn’t changed, it’s air, water shifts, and muscle tone, not fat.

Triggers that actually matter (and the ones that get overblamed)

People with IBS often notice: Symptoms after large, mixed meals (fat + carbs + volume). Worse days after poor sleep. Flares around stressful events or travel. Sensitivity to certain carbs (onions, garlic, beans, wheat for some). Hormonal influence (many women flare around their period)

Meanwhile, they’re often told:

“Just add more fiber”

“Take a probiotic”

“Cut out gluten and dairy”

“Try to relax”

Here’s why that advice often fails.

Fiber is not one thing. There are many types of fiber. Some are fermented rapidly by gut bacteria, producing gas (fermentable fibers like inulin, wheat bran). Others form a gel and move more gently (psyllium). If you have IBS with bloating and someone tells you to “eat more bran,” there’s a decent chance you’ll feel worse.

Probiotics are not magic. Most over-the-counter probiotics are generic strains studied in different populations, at different doses, for different endpoints. Some specific strains help some IBS patients. Many do nothing. A few make people worse (more gas, more bloating).

If a probiotic helps you, great. But it’s not a foundational treatment; it’s a possible tool.

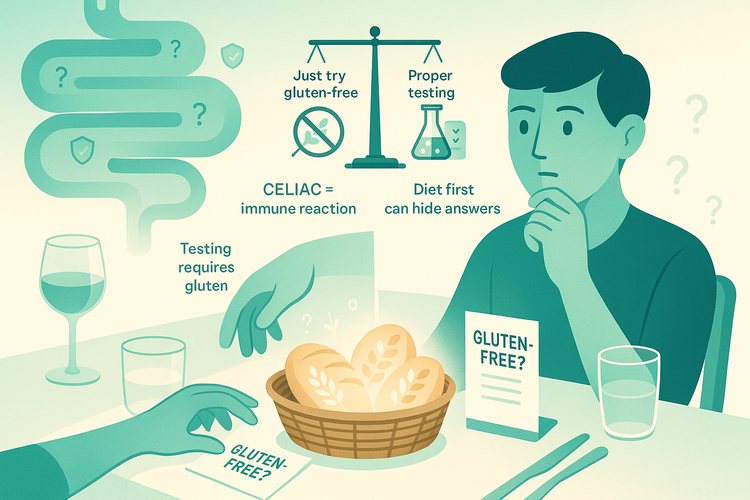

Gluten is often a red herring. Some people truly have celiac disease (autoimmune reaction to gluten), and that must be ruled out. Others have non-celiac wheat sensitivity. But a lot of people who “feel better off gluten” are actually reacting to FODMAPs (fermentable carbs) in wheat, not gluten itself.

So they cut gluten, feel somewhat better, think they’ve solved it, but still have flares because the underlying sensitivity is broader than one protein.

Stress is a modulator, not a character flaw. Does stress affect IBS? Absolutely. The gut-brain axis is real. But “reduce stress” is not a treatment plan. It’s lazy advice if it’s not paired with concrete strategies and an explanation of why it matters. You’re not causing your IBS by “being anxious.” Your nervous system has been trained to overreact to gut signals. That’s different.

The frustration is valid. Most people with IBS: Have had normal scopes and tests, Have been told “it’s IBS” in a 10-minute visit, Leave with vague diet advice and maybe an antispasmodic. You’re left with a label, not a roadmap.

Let’s fix that part.

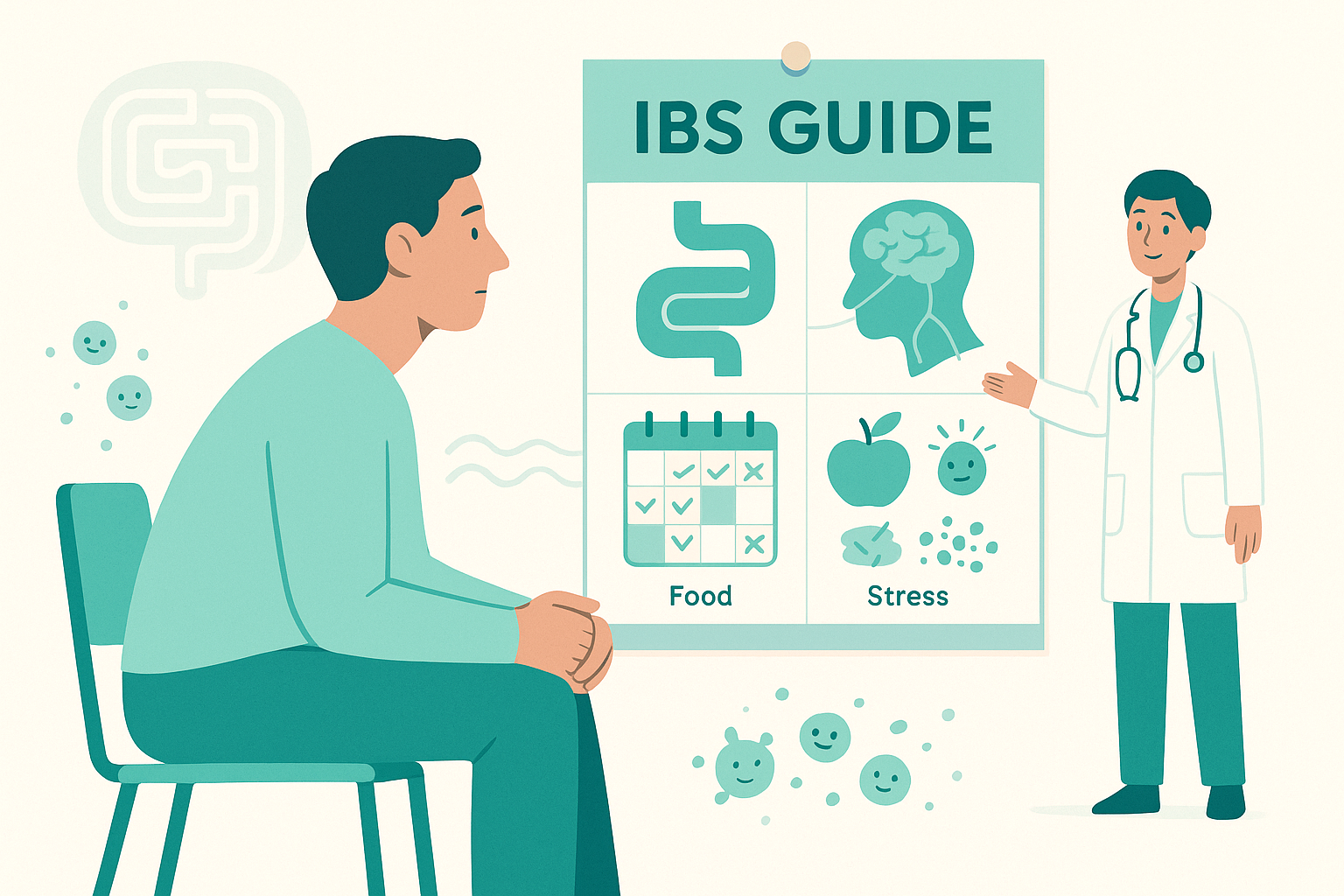

3. A Practical Framework Your GI Brain Uses (But Rarely Explains)

You can’t change your entire gut–brain system overnight. But you can get strategic. Instead of chasing cures, think like a clinician: What pattern am I dealing with, and what levers can I pull?

There are four main levers: 1. Motility (how fast things move) 2. Sensitivity (how loud the signals feel) 3. Fermentation (how much gas is produced) 4. Brain–gut processing (how those signals are interpreted)

You won’t control all of them perfectly, but you can influence each.

Step 1: Know Your Dominant Pattern

IBS is usually categorized as: IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant), IBS-C (constipation-predominant), or IBS-M (mixed)

But I’d add two more practical dimensions: Bloat-dominant vs pain-dominant and Predictable vs random flares

Spend 2–3 weeks tracking:

Stool form (use the Bristol Stool Scale if you want to be precise), Timing of bowel movements, Bloating level (0–10), Pain level (0–10), Meals (roughly what and when, not calorie counting), Sleep quality, and Major stressors.

You’re looking for patterns, not perfection. Things like:

“Every time I eat a big late dinner, I’m miserable the next morning.”

“On days I sleep under 6 hours, my diarrhea is worse.”

“Onions and garlic are repeat offenders.”

“I’m always worse the week before my period.”

This is not busywork. It’s data. It tells you which lever to focus on first.

Step 2: Match the Lever to the Pattern

If motility is a big issue (IBS-D or IBS-C):

For IBS-D: Smaller, more frequent meals reduce the “big wave” contraction after eating. Some people benefit from low-dose loperamide strategically (e.g., before known triggers like long drives), not as a daily crutch. Certain prescription meds slow transit or calm the nerves in the gut wall - worth discussing with your GI if diarrhea is dominating your life.

For IBS-C: Hydration matters, but water alone doesn’t fix slow colon motility. Gentle, soluble fiber (like psyllium) often works better than bran. There are medications that directly stimulate intestinal fluid secretion and motility (linaclotide, plecanatide, etc.). These are not “last resort”, they’re legitimate tools.

The key: if your main issue is stool form and frequency, you need a motility-focused strategy, not just “cut FODMAPs.”

If bloating and gas are center stage:

This is where fermentation and sensitivity collide.

Your colon bacteria ferment carbs you don’t absorb in the small intestine. This is normal. But in IBS, either: You’re getting more fermentable material into the colon (diet pattern), and/or Your bacteria produce more gas from the same input, and/or Your gut is more sensitive to the resulting stretch.

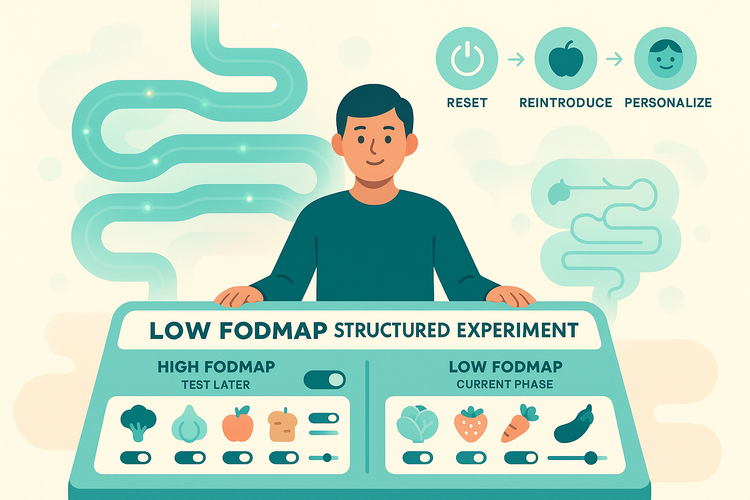

A low FODMAP approach, done properly, is a temporary diagnostic tool, not a forever diet: 1. Short restriction phase (usually 2–6 weeks) to see if symptoms improve. 2. Systematic reintroduction to identify which groups you actually react to. 3. Personalization phase where you liberalize as much as you can tolerate.

The goal is not to live on five “safe” foods. It’s to figure out whether certain carb types are major drivers for you.

If bloating is severe and persistent, sometimes we also evaluate for: Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), Celiac disease, Pancreatic enzyme insufficiency, Other structural issues (anatomy-related)

If pain is the main problem:

Now we’re in sensitivity and brain-gut territory.

Food still matters, but the volume and timing can be as important as the specific ingredients. For example: Large meals stretch the gut more, which can trigger pain in a hypersensitive system. Eating quickly can trap more air and increase distension.

On the nerve side: Certain meds (low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, some SSRIs/SNRIs) are used not for mood, but for visceral pain modulation. They lower the volume on pain signaling. Gut-directed hypnotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have solid evidence in IBS. Not because “it’s psychological,” but because they change how your brain processes gut signals.

Think of it like turning down the gain on a microphone that’s picking up every tiny noise.

Step 3: Build Your Personal “IBS Playbook”

Instead of a rigid protocol, aim for a menu of strategies you can pull from. For example:

You might discover:

“If I sleep 7+ hours, keep my meals smaller, and avoid onions/garlic on workdays, my baseline is 50% better.”

“If I have to travel, I start my constipation med the day before, bring soluble fiber, and avoid big, late restaurant meals.”

“If I’m in a flare, I know a 2–3 day low FODMAP reset plus heat, movement, and my prescribed antispasmodic will get me back to baseline faster.”

None of that is glamorous. But it’s how people move from “my gut controls my life” to “my gut is annoying but manageable.”

A few grounded truths:

There is no single IBS diet that works for everyone. You do not have to cut out entire food groups forever to get better. Supplements are not a substitute for understanding your pattern. If your doctor brushed off your symptoms without ruling out red flags (weight loss, blood in stool, anemia, waking from sleep with pain/diarrhea, strong family history of colon cancer or IBD), that’s not “just IBS” - that’s incomplete workup.

Where medications fit:

Medications are not failures. They’re tools. They can: Smooth out motility, Calm spasms, Modulate pain signaling, Reduce bile acid-related diarrhea, Help with coexisting anxiety or depression that amplifies the gut-brain loop

The best outcomes usually come from combining: Targeted diet changes, Thoughtful use of meds, Gut-brain strategies, and Basic lifestyle levers (sleep, movement) that stabilize the system.

Not from chasing the next miracle protocol on social media.

4. The Big Picture: IBS Is Manageable, But It’s Not One-Size-Fits-All

IBS is your gut’s way of saying, “My wiring is sensitive, my rhythm is off, and my communication lines with your brain are too loud.” It’s not a tumor. It’s not classic inflammation. It’s a functional disorder, which may sound dismissive, but actually means there’s room to retrain the system.

You’re not going to meditate your way out of it. You’re also not going to supplement your way out of it. But with the right combination of pattern recognition, targeted diet tweaks, gut-brain work, and (when needed) medication, most people get their lives back to something that feels normal enough.

In future pieces, we’ll dig into specific levers, including: low FODMAP without losing your mind, how gut-directed hypnotherapy actually works, and when to suspect something more than IBS. For now, the win is this: you understand the mechanisms, you know why the generic advice failed you, and you have a framework to start making your gut less of a mystery and more of a system you can work with.