Why Fiber Makes Some People Worse

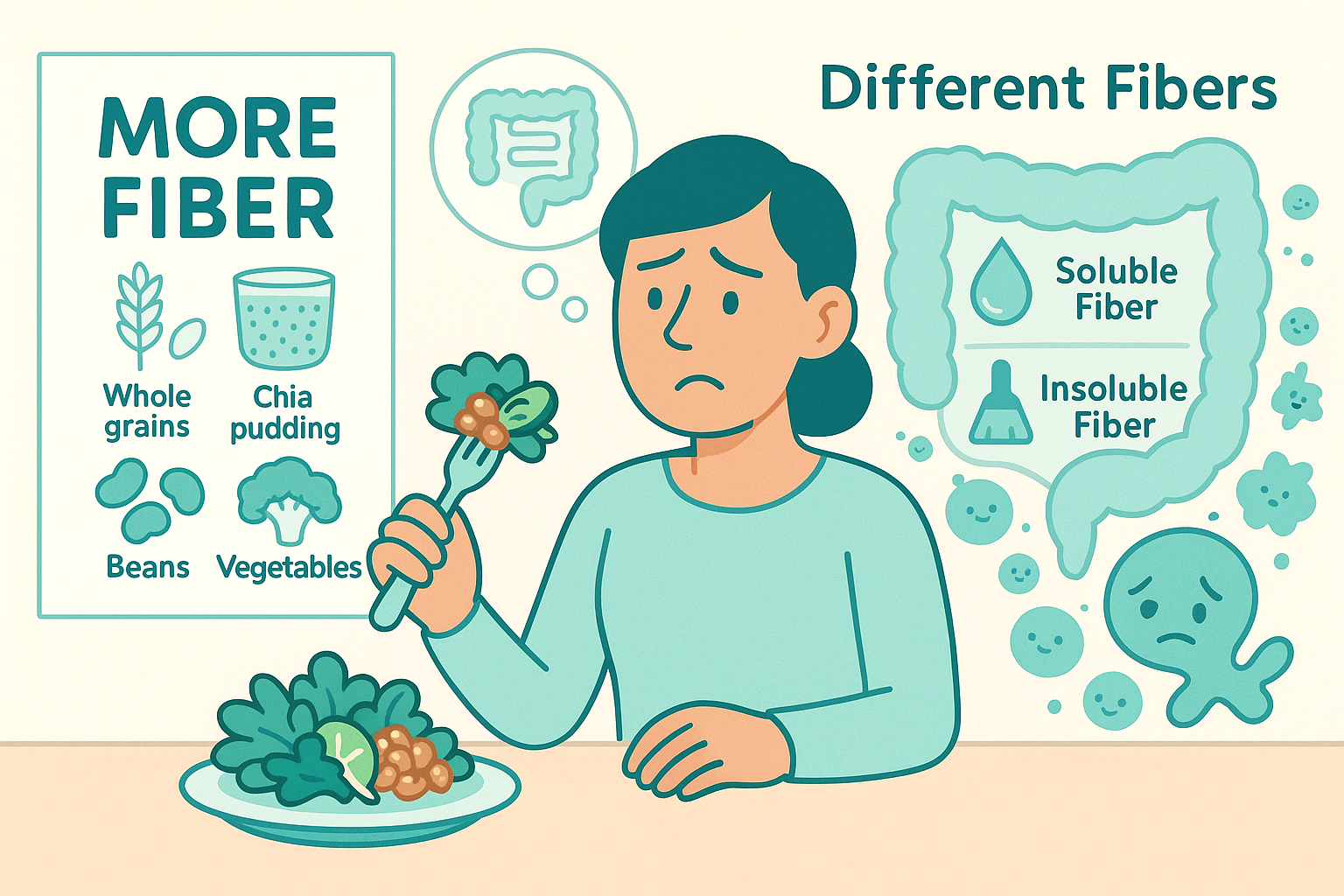

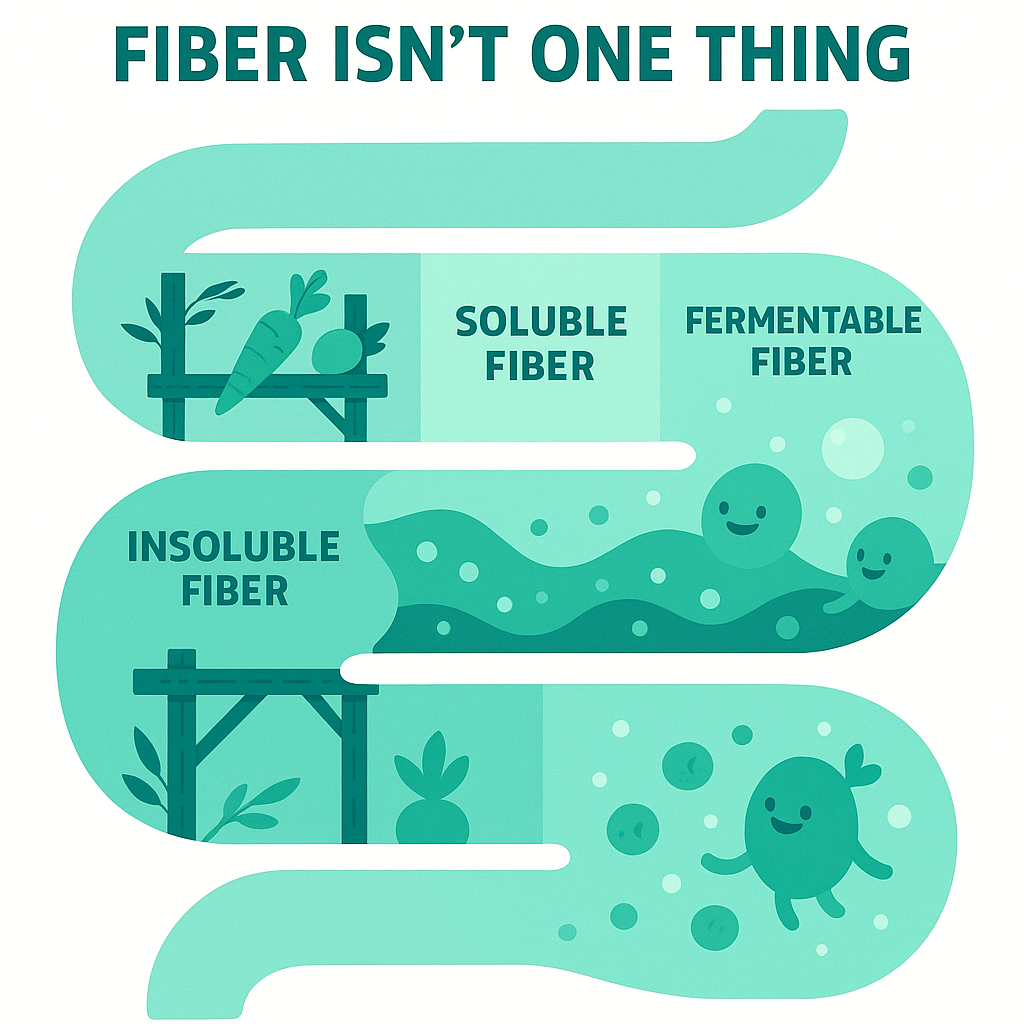

“Fiber” gets talked about like a single nutrient, but physiologically it’s three very different jobs rolled into one word.

First, insoluble fiber—the roughage in wheat bran, many raw vegetables, whole grain skins. Think of it as scaffolding. It doesn’t dissolve in water; it just adds bulk and helps sweep things along. In a colon that’s already moving fast, that extra bulk can feel like someone turned up the turbulence.

Second, soluble fiber—the gel-formers like psyllium, oats, some fruits. This type dissolves in water and turns into a soft gel. It holds onto water in the stool, which can soften hard, dry stools and firm up very loose ones. It’s a bit of a buffer.

Third, fermentable fiber—often called prebiotics: inulin, FOS, GOS, and many fibers in beans, onions, wheat, and some fruits. Your gut bacteria love this stuff. They ferment it and produce gas and short-chain fatty acids. Those fatty acids can be beneficial. The gas, in a sensitive IBS gut, can be brutal.

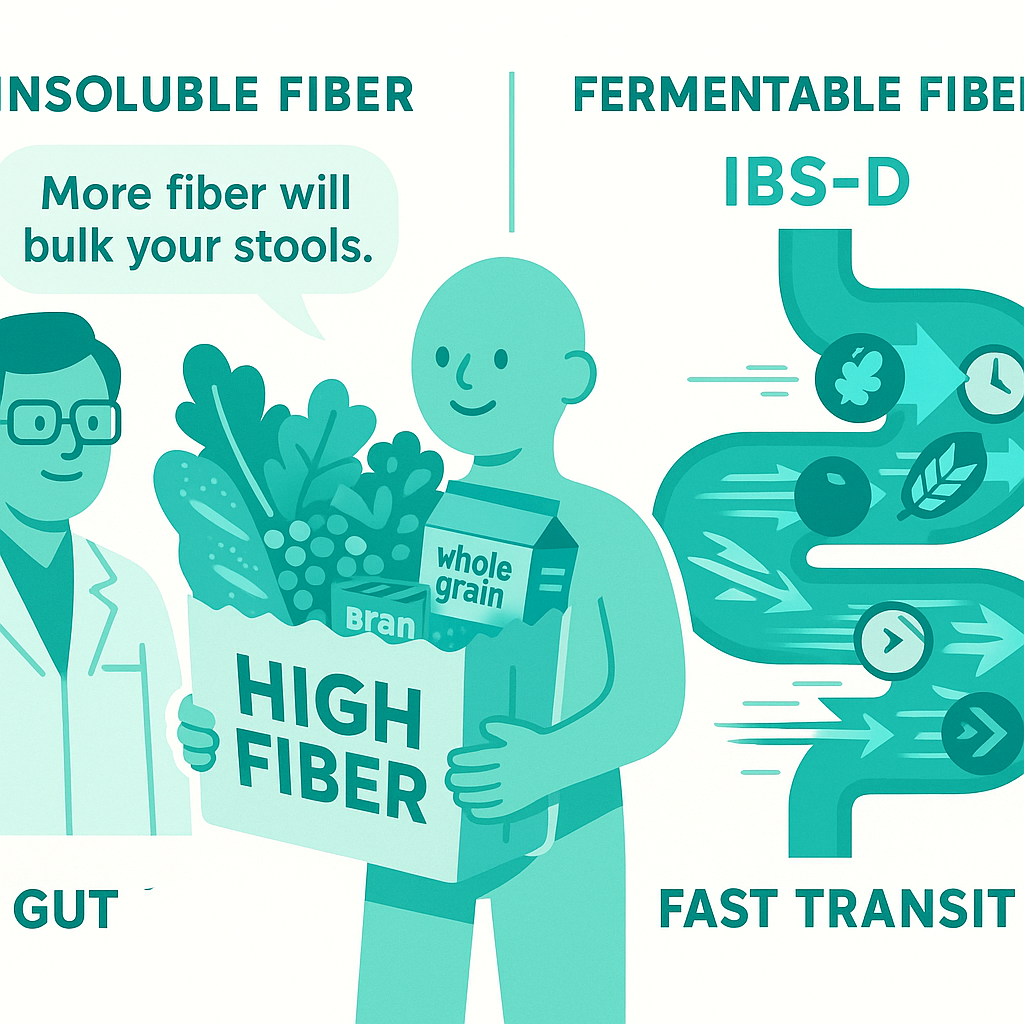

Now layer in transit speed—how fast things move from mouth to toilet. Slow transit? You’re backed up, dry, straining. Fast transit? You’re rushing to the bathroom, maybe multiple times a day. Throw the wrong fiber type into the wrong speed, and symptoms ramp up instead of calming down.

Clinical Reality: How This Shows Up In Real Life

Here’s what I see over and over in clinic.

Someone with IBS-D or fast transit is told, “More fiber will bulk your stools and regulate you.” They load up on whole wheat, big raw salads, lentils, and “high-fiber” cereals. That’s a heavy hit of insoluble plus fermentable fiber, in a colon that’s already pushing things through quickly and reacting to gas. Result: more urgency, more cramping, more bloating, sometimes looser stools.

On the other side, someone with IBS-C or slow transit is told the same thing. They add a lot of wheat bran or raw veg quickly. If their colon is very slow, all that extra bulk just sits there drying out. More distension. More pain. No actual improvement in frequency. Then they’re told to “drink more water” as if that alone will fix colon motility.

And in both groups, fermentable fibers (like inulin in “gut healthy” bars, or chicory root in “high-fiber” snacks) can massively increase gas. If your gut is hypersensitive—a hallmark of IBS—that normal amount of gas feels like a balloon being inflated inside you.

So you’re told fiber is “gentle” and “natural,” but your lived experience is: I did what they said, and my gut went off the rails. That disconnect is understandably infuriating. The problem isn’t that fiber is bad; it’s that “more fiber” without specifying type and timing is lazy advice for a complex system.

Practical Framework: Matching Fiber To Your Gut

Instead of “more fiber,” think “which fiber, for which gut, at what speed?” This is about pattern tracking, not rigid rules.

First, get a rough sense of your baseline transit over a typical week. Are you closer to: – Mostly loose/urgent, going ≥3 times a day? That’s fast transit. – Going every 2–3 days or less, hard to pass, pebble-like? That’s slow transit. You don’t need perfection—just which direction you lean.

If you lean fast (IBS-D pattern), your colon doesn’t need a ton of extra bulk or heavy fermentation right away. In this situation, insoluble fiber bombs (bran cereals, huge raw salads, dense whole grain crusts) and strongly fermentable fibers (inulin, chicory, large amounts of beans) often backfire.

A gentler experiment is lower-fermentable, mostly soluble fiber like psyllium husk, oats, or chia—introduced in small, consistent amounts. These can help form a more cohesive, less urgent stool without throwing gasoline on the gas fire. You’re watching: does this reduce urgency and cramping over 1–2 weeks?

If you lean slow (IBS-C pattern), you may ultimately benefit from some insoluble fiber to give the colon something to push against—but dumps of raw veg or bran rarely go smoothly at first. Again, starting with soluble fiber (psyllium is the most studied) is often better tolerated, because it pulls water into the stool and softens things. Once that’s stable, very gradual additions of insoluble sources can be tested.

Across both patterns, treat highly fermentable fibers as variables, not virtues. If every “gut health” product you add has inulin or chicory and your bloating skyrockets, that’s data, not failure. You can dial those down without swearing off fiber altogether.

Key idea: change one fiber variable at a time for 1–2 weeks. Type (soluble vs insoluble vs clearly fermentable), amount, or timing—not all three at once. Note stool form, frequency, gas, and pain. Your gut’s response is the lab result.

Closing: It’s Not You, It’s The Advice

Your reaction to fiber isn’t irrational or “all in your head.” It’s physiology. Different fibers behave differently in a fast vs slow, sensitive vs less sensitive gut. When you match the fiber type to your transit pattern instead of following generic “more fiber” slogans, things start making more sense.

In the next piece, we’ll get into why your friend can eat a chickpea salad with no problem while you inflate like a balloon—same foods, completely different gut chemistry.