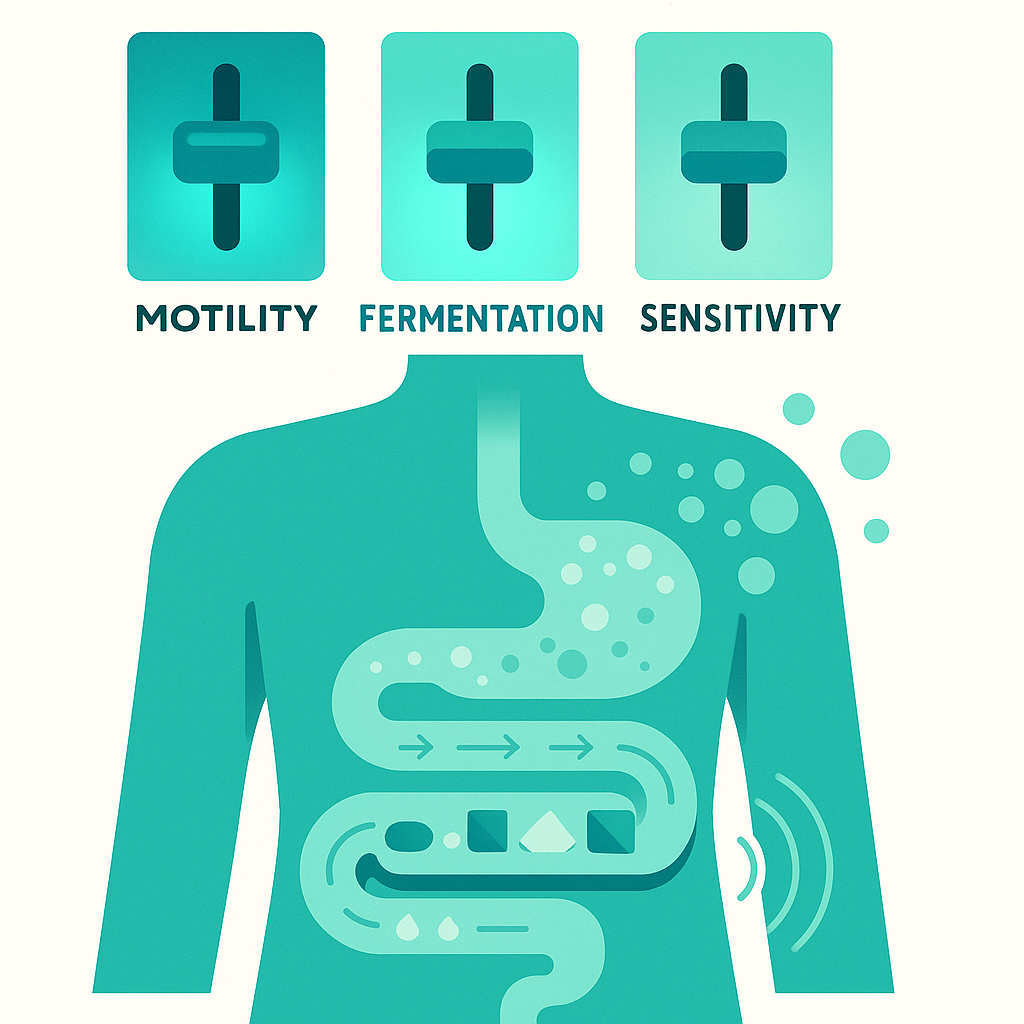

The Three Things Actually Driving Your Symptoms

Under all the noise, three things are doing most of the work: motility, fermentation, and sensitivity.

Motility is how fast stuff moves through your gut. Think of your intestines as a long conveyor belt. If the belt runs too fast, you don’t absorb enough water and you get diarrhea. If it runs too slow, your stool dries out, backs up, and you get constipation, pressure, and that “rock in my abdomen” feeling.

Fermentation is what your gut bacteria do with leftovers. They eat fibers and certain carbs you don’t digest, and in return they produce gas and short-chain fatty acids. Some gas is normal. But if there’s a lot of fermentable material, or the gas can’t move or be absorbed well, you get bloating, distension, and discomfort.

Visceral sensitivity is the volume knob on your gut’s alarm system. The intestines send signals to the brain all day. In IBS, that system is turned up. A normal amount of gas or stretching feels like pain, burning, or urgency. The bowel may not be damaged, but the messages are amplified.

Most IBS is some combination of these three levers set to the wrong levels.

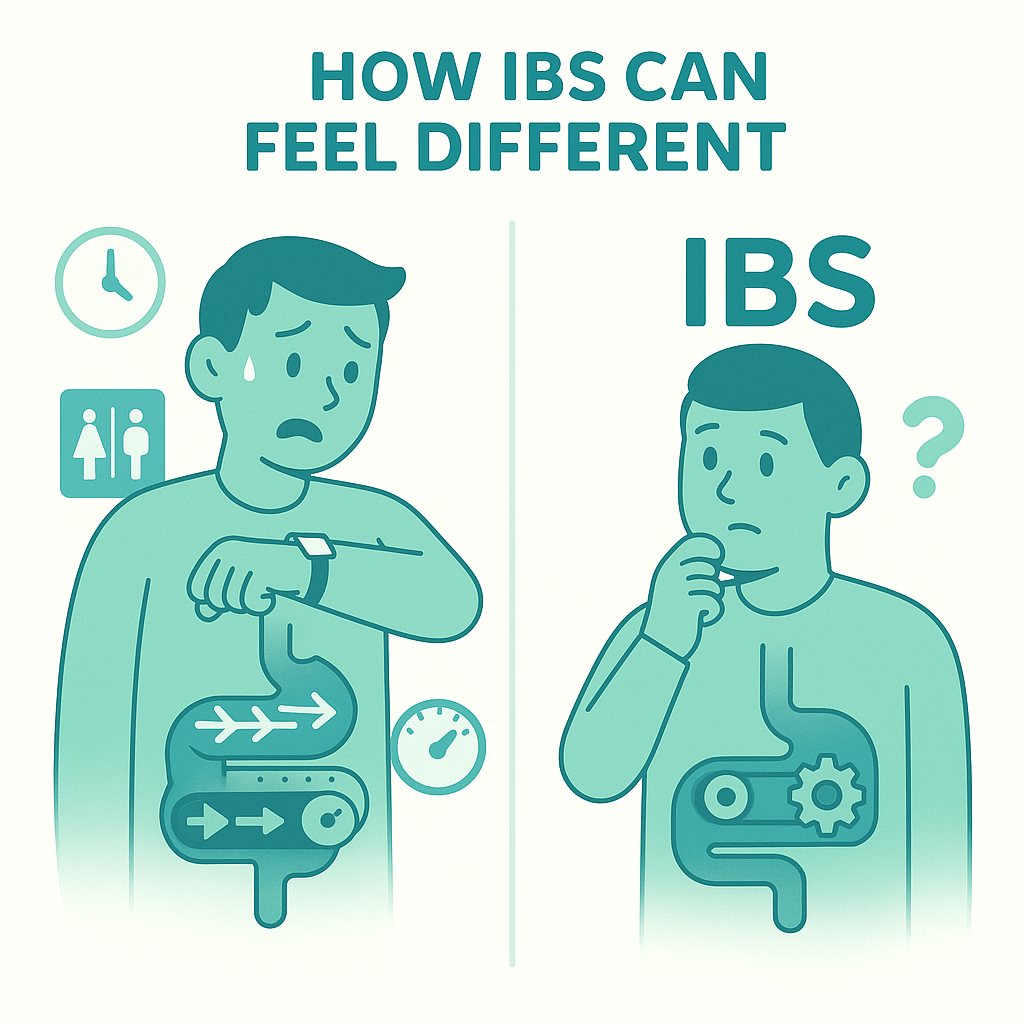

Clinical Reality: How This Actually Feels in Real Life

This is where the confusion starts. You and your friend both have “IBS,” but the engines under the hood are different.

If your motility is fast, you see it: loose stools, urgency, going three times before leaving the house. Meals might “go right through you” (they don’t literally, but your colon speeds up in response to eating). Fatty meals, caffeine, or big portions can feel like someone hit the turbo button on your gut.

If your motility is slow, things are sneakier. You may go every day but never feel fully empty. Or you go every few days, and in between you look six months pregnant by 4 pm. You can have both constipation and bouts of loose stool as backed-up material finally pushes through.

Now layer fermentation on top. Two people eat the same chickpeas. One gets mild gas and moves on. The other gets tight upper abdominal pressure, bloating that worsens as the day goes on, gurgling, and maybe reflux. It’s not that the food is “toxic.” Their bacteria, motility, and gas handling are just set up differently.

Then comes visceral hypersensitivity. Some people have a colon full of gas and feel nothing. Others have a modest amount of gas and feel sharp pains, burning, or that horrible “I’m going to explode” sensation. Scans often look “normal” because structurally, they are. The nerves and brain-gut signaling are the issue.

This is why conventional advice fails you. “Just eat more fiber.” Great if slow transit is your main issue and you tolerate fermentation. Miserable if your wiring is sensitive and bacteria are overenthusiastic gas factories. Generic advice assumes everyone’s three levers are set the same. They aren’t.

Practical Framework: Finding Your Dominant Drivers

You don’t need to micromanage every molecule you eat. You do need to figure out which 1–2 of these three are mostly running your show.

Start with motility patterns. Ignore food for a moment and just watch timing and form. Are you more diarrhea-predominant, constipation-predominant, or mixed? Do you tend to hurry to the toilet within an hour of eating, or do you go days between meaningful movements? Fast transit leans toward urgency and cramping after meals. Slow transit leans toward fullness, heaviness, and relief after a big bowel movement.

Next, pay attention to fermentation signals. Notice when bloating peaks. Classic fermentation pattern: relatively flat in the morning, slowly expanding through the afternoon, worst in the evening, sometimes with a “bloat hangover” the next day. If you track meals for 3–5 days, patterns often emerge: certain carbs (beans, wheat, onions, some fruits) trigger more gas and distension than others. That doesn’t mean those foods are evil; it means your current bacterial setup and motility don’t handle them gracefully.

Then consider sensitivity. Ask: how out-of-proportion is the pain to what’s actually happening? If small meals cause big pain, or gas you can’t even see on your belly feels unbearable, or you’re wiped out by sensations others would call “mild discomfort,” sensitivity is a major driver. Stress and sleep disruption often crank this volume knob even higher, which is brain-gut, not “it’s all in your head.”

Most people with IBS have one or two dominant levers. For example: - Fast motility + sensitivity → urgency, cramping, “I can’t be far from a bathroom.” - Slow motility + fermentation → bad evening bloat, constipation, relief after large movements. - Fermentation + sensitivity → a lot of gas/pain with relatively okay bowel frequency.

Once you see your pattern, advice stops being random. A slow-motility-dominant person will approach fiber differently than someone with fast transit. A sensitivity-dominant person benefits more from nervous-system–calming strategies and graded exposure to foods than from extreme elimination diets.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s understanding which levers matter most in your gut, so changes feel targeted, not desperate.

Closing: The Takeaway

IBS isn’t chaos; it’s three main systems—motility, fermentation, and sensitivity—set to unhelpful levels. Your job isn’t to fix everything at once. It’s to notice which levers are loudest and work with those first.

In the next pieces, we’ll break these down one by one and talk about how to experiment—without burning your life down to a list of three “safe” foods.