The Post-Meal Bloating Pattern

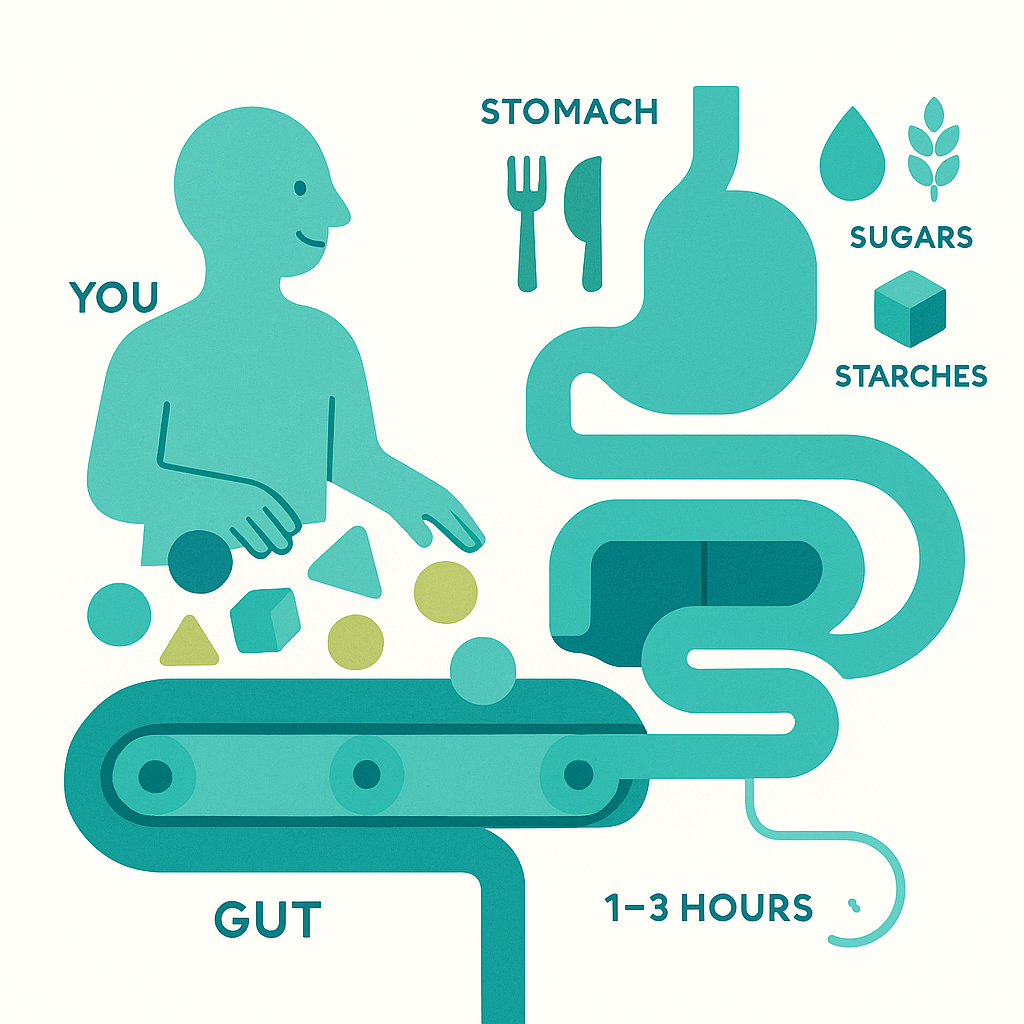

Think of your gut as a conveyor belt with two major players: you and your microbes.

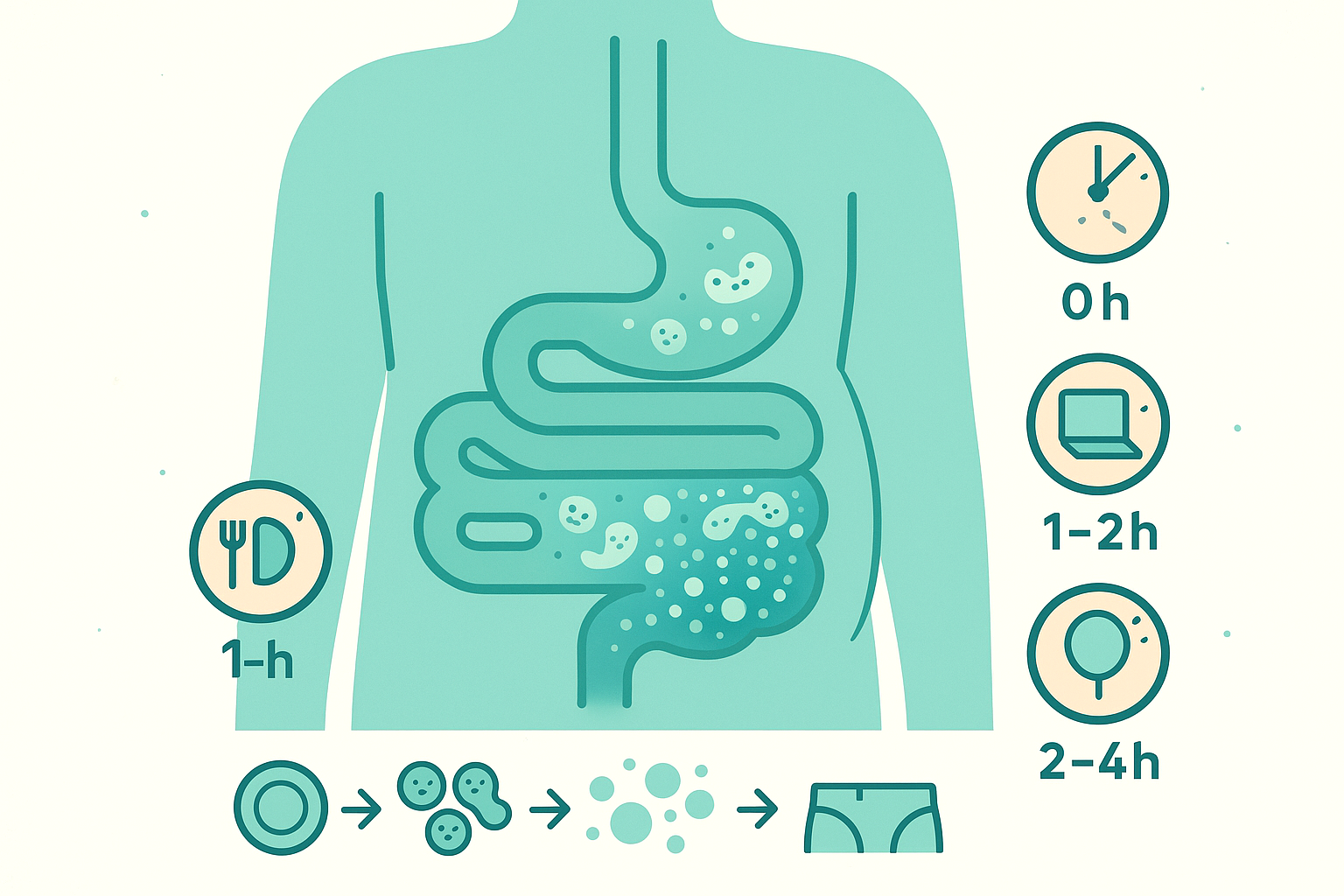

First phase: your stomach and small intestine. That’s where you do most of the work—breaking down protein, digesting fats, absorbing sugars and starches. This phase usually takes 1–3 hours after a meal. During that time, gas production is relatively low unless you swallow a lot of air or have very rapid transit.

Second phase: the colon. That’s your internal fermentation tank. Whatever wasn’t fully digested upstream—certain carbs, fibers, sugar alcohols, some starches—gets delivered to your gut bacteria. They don’t waste time. Within about 2–4 hours after a meal, they start actively fermenting those leftovers, producing gas: hydrogen, methane, carbon dioxide.

If your small bowel transit is a bit faster, or your small intestine doesn’t absorb carbohydrates efficiently, more “fuel” hits the colon earlier and in larger amounts. More substrate + hungry bacteria = more gas, more quickly.

Then layer on visceral hypersensitivity (nerves that are extra reactive) and sluggish gas clearance (poor motility or pelvic floor issues), and a normal amount of gas can feel like a pressure cooker. That’s why the timing and intensity feel so specific and why it peaks hours, not minutes, after eating.

Clinical Reality

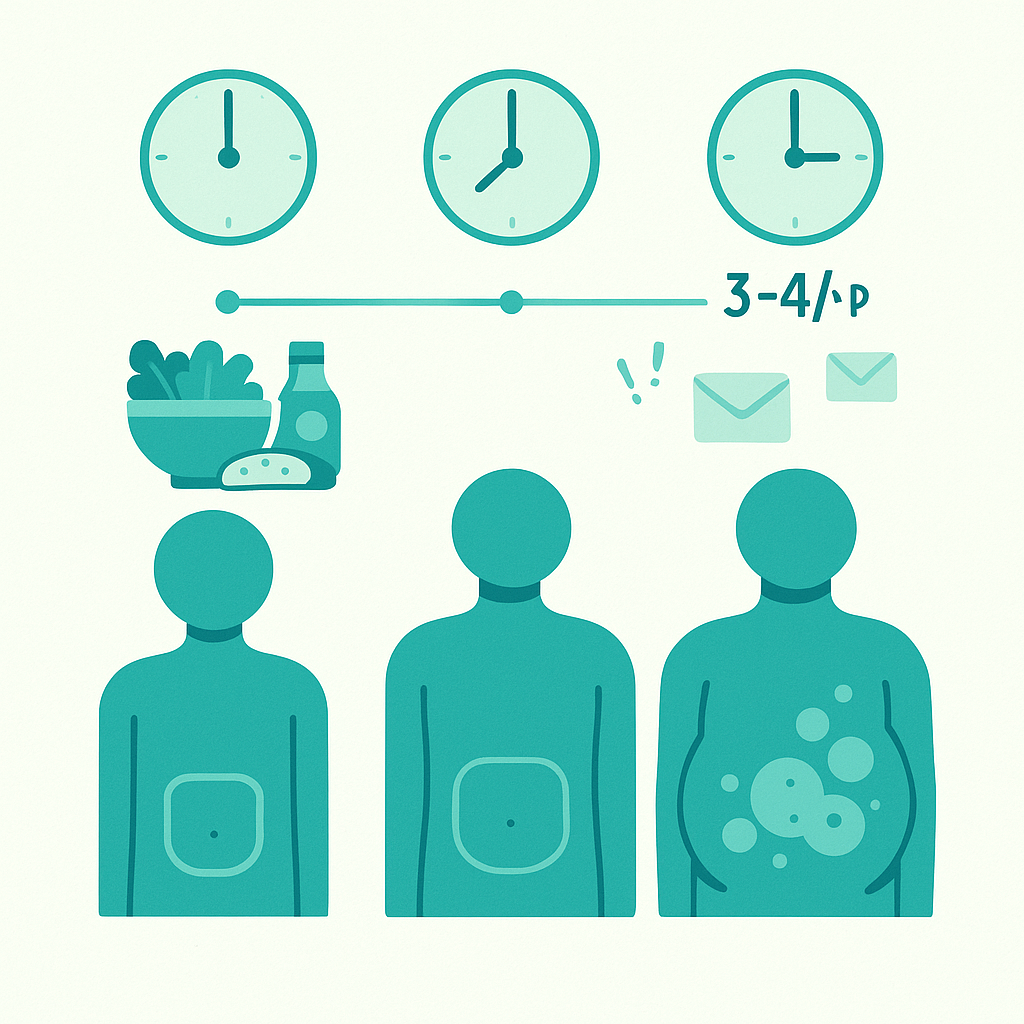

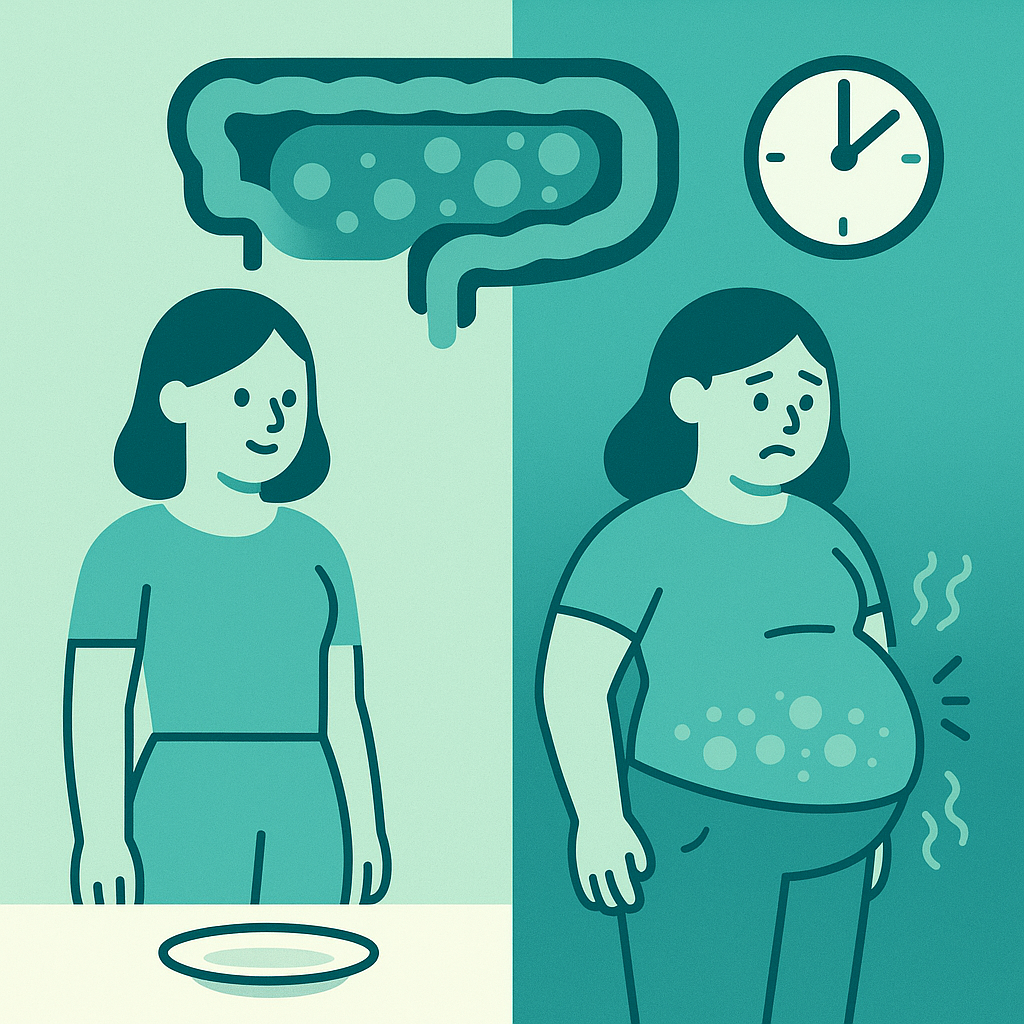

In real life, this looks very familiar: you eat at noon, feel pretty normal until about 2pm, and by 3pm your abdomen feels tight, rounded, and uncomfortable. If you check a mirror, you can literally see the difference. Morning: relatively flat. Late afternoon: “six-months-pregnant” bloat.

Notice how breakfast sometimes doesn’t do this, but lunch and dinner do? That’s because the system is already “pre-loaded” with earlier meals, and the total fermentable load starts stacking. The second or third meal of the day hits a colon that’s already active and full of partially digested leftovers.

Standard advice like “eat more fiber” or “it’s just stress” often falls flat here. If your colon bacteria are already having an all-day buffet, adding a huge dose of fiber without a plan can make the 2–4 hour peak even worse. You’re not imagining that your “healthy” lentil salad causes more issues than a boring plate of eggs.

This pattern is frustrating because it feels so precise yet so confusing. You think, “But I felt fine right after I ate—so it can’t be the food.” In IBS, that timing actually points directly at fermentation, motility, and transit, not food allergy or immediate intolerance.

Practical Framework

Instead of random food elimination, treat your bloating like a timing puzzle.

Start by mapping it: write down the time you eat, what you eat in broad strokes (higher fat, higher carbs, lots of fiber, liquid vs solid), and when the bloating hits. Over a week, you’ll often see consistent windows: “Lunch at 12 → bloating 2–4pm,” “Dinner at 7 → bloating 9–11pm.”

Now layer in meal composition. High-fat meals (creamy sauces, fried foods, heavy cheese) slow stomach emptying and small bowel transit. That can delay when food reaches the colon, so your fermentation peak may shift later, but can feel more prolonged. Carbohydrate-heavy meals—especially with fermentable carbs (wheat, onions, beans, certain fruits, sugar alcohols)—tend to front-load more substrate into the colon, creating a more intense 2–4 hour peak.

Protein is a bit different. It doesn’t ferment into gas as aggressively as carbs, but very large protein portions with a lot of fat can slow motility and indirectly change the timing and distribution of fermentation. So it’s not that “protein causes bloating,” it’s that big, fatty, mixed meals change the schedule and sometimes the location of gas production.

Transit time is the other big variable. Faster transit into the colon means earlier peaks. Slower transit means later, longer, and often more uncomfortable gas accumulation. People with IBS can have segments that are too fast and others that are too slow, so gas gets trapped instead of moving along.

So the framework:

You’re looking for patterns like: “High-carb, high-FODMAP lunch → sharp 2–3 hour peak” versus “Very fatty dinner → slower, later, more prolonged pressure.” That gives you levers to test—slightly smaller portions of fermentable carbs at one meal, spacing fiber doses, or shifting more fat away from the meals that already trigger the worst timing.

Not rules. Not a forever diet. Just controlled experiments based on where in the tube things are likely happening and when your microbes clock in for work.

Closing

If your bloating shows up 2–4 hours after meals, your gut isn’t being random. It’s following a fairly logical schedule: digestion first, fermentation second, symptoms when gas plus sensitive nerves plus motility all intersect.

Once you start tracking what you ate and when the bloat hits, the pattern gets a lot less mysterious—and a lot more workable. Next, we’ll zoom in on specific carb types and how to tell whether your microbes are overfed, under-managed, or just badly timed.