Morning vs Evening: Why Timing Matters

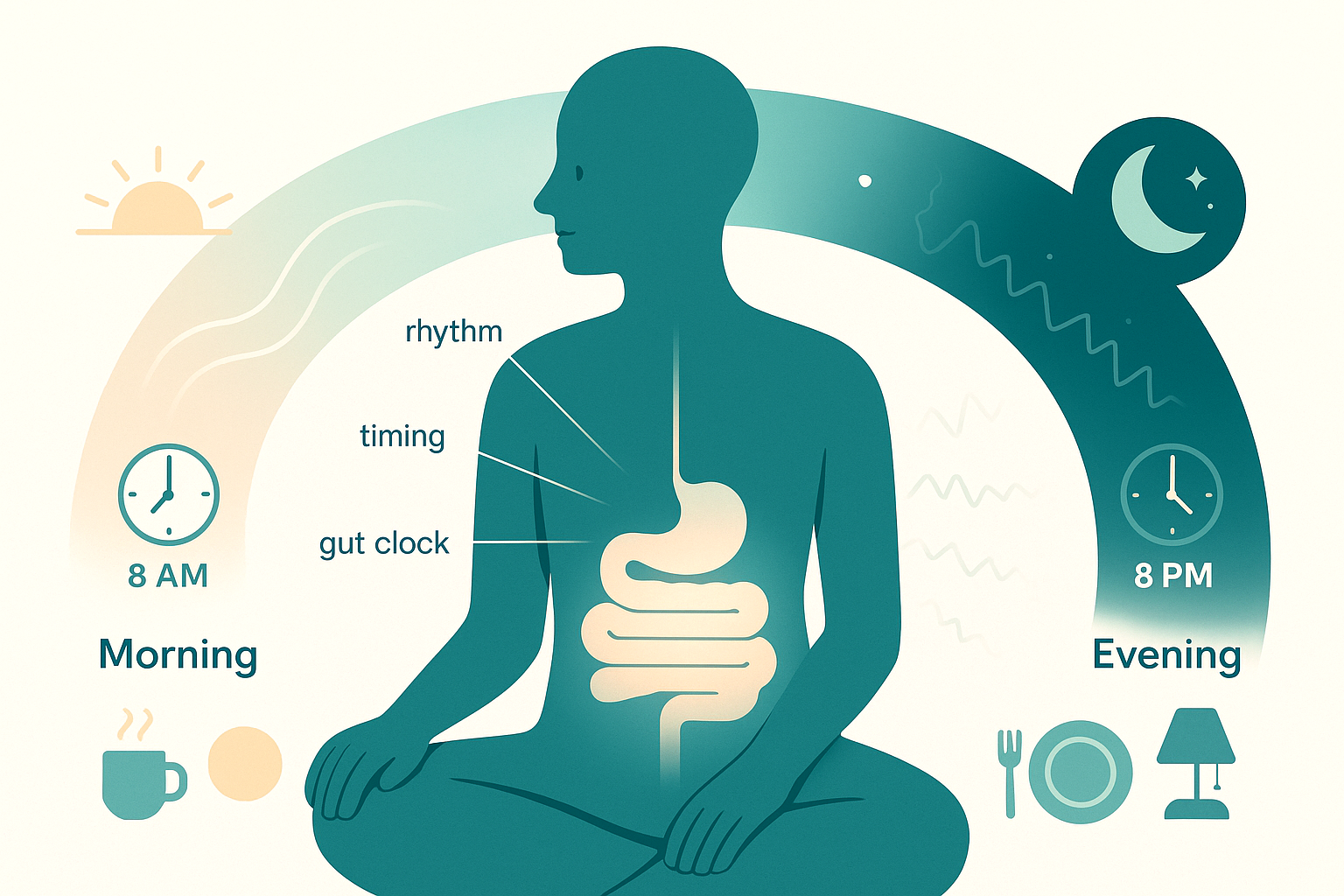

Your brain isn’t the only thing that runs on a 24-hour cycle. Your gut does too.

You have a circadian rhythm—an internal clock that tells cells when to be “on” and when to power down. Your intestines have their own version of this. They don’t just move food at a constant rate all day. They have patterns.

During the day, especially in the morning and early afternoon, gut motility—the coordinated squeezing that pushes stuff along—is more active. Think of it like rush hour traffic: lots of movement, frequent “waves” of contractions moving food forward.

As evening comes, motility naturally slows down. Your gut is preparing for the sleep phase, where it does more repair work and less active transport. But if you have IBS, that shift can feel exaggerated or chaotic. Instead of a smooth slowdown, you get stop–start movement, gas pockets, and cramping.

At the same time, bacteria in your colon are constantly fermenting whatever makes it down there. During the day, each meal adds to that fermentation load. The more that builds up and the slower the movement becomes, the greater the chance you feel distension, gas, and pain in the evening—even if you didn’t change what you ate.

Clinical Reality: Why Evenings Feel Like the Enemy

Here’s how this plays out in real life.

You might wake up with some mild discomfort or urgency, maybe get that classic IBS “morning clear-out” after breakfast. Then the day settles. Around lunchtime you feel…not perfect, but functional.

By late afternoon into evening, things change. Your belly looks 4–5 months pregnant. Or you feel tight, full, and pressured high up under the ribs. Or you start getting those sharp, left-sided cramps. Sometimes the urge to go to the bathroom appears, but not much happens. Other nights, it’s the opposite: suddenly you can’t get off the toilet.

Standard advice usually misses the timing angle. You’re told to “eat more fiber,” “drink more water,” “cut out dairy,” or “avoid stress.” None of that explains why your symptoms are time-locked—why 8 pm feels like a different disease than 10 am.

This is where frustration spikes. You look at your dinner and blame that one meal. But often, dinner is just the last straw on a whole day of motility and fermentation dynamics that started at breakfast.

When nobody explains the circadian side of gut function, you’re left feeling like your body is random or “all in your head.” It isn’t. The timing makes sense once you zoom out.

A Practical Framework: Think 24-Hour Gut, Not Single Meal

Instead of asking, “What did dinner do to me?” try, “What did the whole day add up to by evening?”

First layer: circadian motility. Your gut tends to move better earlier in the day, then gradually slows. If you front-load most of your calories and fermentable carbs (things like certain fibers, wheat, onions, garlic, beans, some fruits) into breakfast and lunch, you build up a fermentable “queue” in the small and large intestine. By the time your natural motility is dialing down in the evening, that queue is still there, producing gas.

Second layer: meal accumulation. Each meal isn’t replacing the previous one; it’s stacking on top of what hasn’t fully moved along yet. If motility is a bit sluggish (very common in IBS-C, and still relevant in mixed-type IBS), the colon becomes a crowded waiting room. Bacteria get more time with those carbs → more fermentation → more gas and distension → you feel worse toward the end of the day.

Third layer: sleep-wake cycle. When you sleep, gut motility slows even more, especially in the colon. In IBS, this can mean you “carry” the previous day’s load into the next morning. That’s why some people wake up already bloated or needing several trips to the bathroom after breakfast: sleep didn’t reset the system as cleanly as it does for others.

So what do you do with this?

You don’t need rigid rules; you need patterns. For a week or two, track time of day, not just foods. Note when you eat, when you bloat, when you have bowel movements, when gas peaks, and how you slept.

People often notice consistent themes, like:

- Earlier, moderate meals = calmer evenings - Long fasting then a large late lunch or dinner = evening explosion - Poor sleep = worse motility next day, more stacked fermentation

From there, experiments become more logical. Maybe you shift a portion of your most fermentable foods earlier when motility is better, or you spread them more evenly instead of loading them into two big meals. Maybe you avoid adding a large, very fermentable dinner onto a day that already felt slow and backed up.

None of this cures IBS. But once you see your gut as a 24-hour system with a clock, your symptoms stop feeling random—and you get knobs you can actually turn.

Your gut isn’t betraying you at 8 pm; it’s following a rhythm that’s out of sync with your comfort. Evening flares are often the end result of how your motility, meals, microbes, and sleep stacked up across the whole day—not a single “bad” dinner.

Next time, we’ll dig into those morning patterns: why some people live in the bathroom before 10 am, and what that says about their gut’s internal clock.