Does Gut Microbiome Matter?

Think of your gut as a long fermentation chamber running from your mouth to your rectum. Food goes in, you digest the bits you can, and what’s left becomes fuel for microbes—trillions of bacteria that live mostly in your colon.

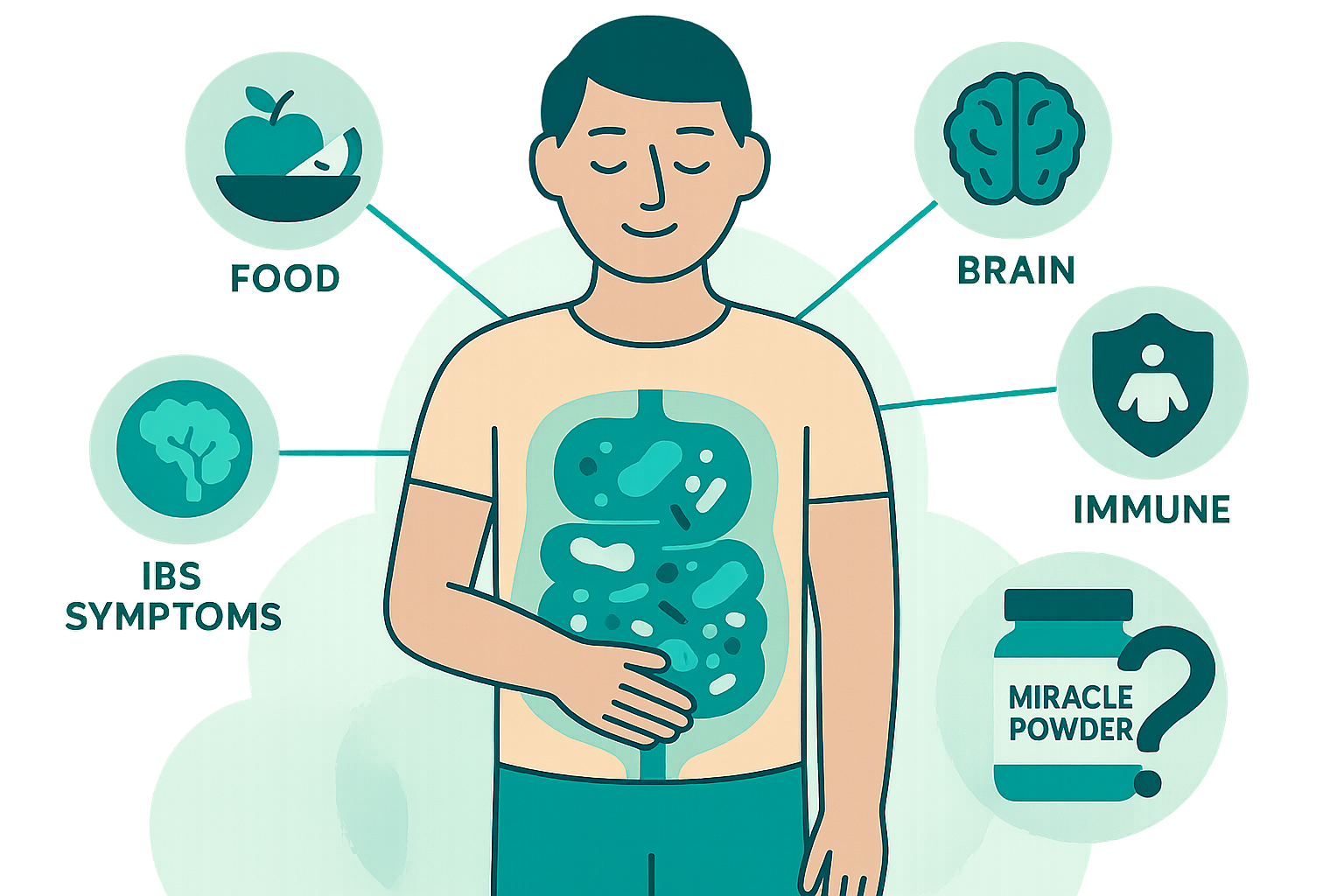

These microbes do three big things that matter for IBS.

First, they ferment carbohydrates you don’t fully absorb. That fermentation makes gas: hydrogen, methane, carbon dioxide. Gas itself is normal. The problem in IBS is less “you have gas” and more “your gut nerves overreact to it.” Same volume, more pain.

Second, microbes turn food into chemical messages. They produce short-chain fatty acids (like butyrate) that talk to your immune system, your gut lining, and even the muscles that push things along. If the mix of bacteria shifts, the mix of signals shifts too—changing motility, sensitivity, and inflammation on a microscopic level.

Third, certain microbes influence motility. Methane-producing bugs, for example, tend to slow transit down. Slower colon, more constipation, more time for fermentation, more bloating. Too-fast transit in others means more urgency and loose stool.

So yes, the microbiome matters. Not as a mystical “gut health score,” but as a chemical factory that affects gas production, speed of movement, and how irritable your gut nerves feel.

Clinical Reality: How This Shows Up in Real Life

Here’s what this looks like in day-to-day IBS life, not in a lab.

You eat the same bowl of chickpeas your friend eats. They get mild gas and move on with their day. You get a tight, ballooned belly that makes you unbutton your pants at 3 p.m. The amount of gas might be similar. Your gut just interprets that stretch as threat instead of background noise.

Or you notice that high-fiber days swing you toward worse constipation and pressure. That’s not “fiber is bad.” It’s that your current combination of bacteria, gut motility, and sensitivity means added fermentable material becomes more trapped gas in a slower-moving tube.

On the social side, you see endless ads for microbiome tests claiming they can “tell you exactly what to eat.” The evidence for that? Weak at best. We don’t have a validated way to look at a stool sample, read the bacteria list, and accurately tell you which foods will hurt or help your IBS.

Conventional advice also swings too simple: “Just eat more fiber,” “Just take a probiotic,” “Just relax, it’s stress.” None of those account for how your particular gut is reacting to what your microbes do with your food.

You’re not imagining it. The microbiome is involved. But it’s not a single villain you fix with a supplement; it’s part of a system that’s become hypersensitive and out of rhythm.

Practical Framework: Using Microbiome Science Without the Hype

Here’s a way to think about your microbiome that’s actually useful: less as a target to “fix,” more as a partner you’re negotiating with.

Instead of starting with expensive tests, start with pattern tracking around three things: gas, timing, and texture.

Pay attention to what happens when you eat different types of fermentable carbs: beans, onions, wheat, apples, sugar alcohols (like sorbitol, xylitol), and very high-fiber products. These are classic “microbe fuel.” If you get a delayed, gassy, pressure-y response a few hours later, that’s your microbiome weighing in.

Notice your transit pattern. Are you mostly C (constipation), D (diarrhea), or M (mixed)? People with constipation often have more methane-producing microbes and slower motility. That means super-high-fiber “gut health” diets can backfire by overloading a system that’s already slow. People with diarrhea-predominant IBS often react more to fat and large meals than to pure fiber.

When you adjust your diet, think gradual experiments, not permanent rules. Cutting all fermentable carbs (FODMAPs) forever is not the goal. A structured, short-term low FODMAP trial followed by systematic reintroduction has decent evidence for IBS. What it’s really doing is giving your microbes less fermentable fuel for a while so your sensitive gut has a chance to calm down. Then you figure out which categories you personally tolerate.

Probiotics? Some strains help subsets of IBS patients, but they’re not microbiome magic. Evidence is mixed, effect sizes are modest, and it’s very strain-specific, not “any probiotic will do.” They’re a tool to test, not a cure.

The bigger, boring truth is that your microbiome responds to patterns over time, not single hero foods. Regular meals, not constantly grazing. Fiber increases in small, steady steps, not overnight. Enough overall calories so your body isn’t in constant stress mode.

And there’s this uncomfortable research reality: two people can have very different microbiomes and very similar symptoms, or very similar microbiomes and very different symptoms. So your best data set is still you—your symptoms, your food, your timing—not a color-coded microbiome report.

Closing: What Actually Matters for You

Your microbiome matters for IBS because it controls fermentation, chemical signaling, and part of how fast or slow things move. But it’s not a personality test, and it’s not a one-button fix. The real power is using microbiome science to make sense of your patterns, not to scare you into buying powders.

In the next pieces, we’ll dig into specific levers—like FODMAPs, motility, and nerve sensitivity—so you can see where microbiome fits and where it’s getting too much credit. For now, think less “heal your microbiome,” more “understand how your gut and its bacteria are reacting together.”